149

Plant Science Bulletin 56(4) 2010

WINTER 2010

VOLUME 56 NUMBER 4

PLANT SCIENCE

ISSN 0032-0919

The Botanical Society of America: The Society for ALL Plant Biologists

THE BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA

Leading Scientists

and

Educators

since 1893

BULLETIN

News from the Society

BSA Awards........................................................................................150

Good Green Teaching Colleagues.........................................................151

BSA Education News and Notes.........................................................154

In Memoriam

Lawrence Joseph Crockett (1926-2010)..............................................157

Personalia

Dr. Peter Raven receives the William L. Brown Award for Excellence in

Genetic Resource Conservation............................................160

Friedman named Director of Arnold Arboretum....................................160

Special Opportunities

New Non-Profit Directly Links Donors to Researchers......................162

Harvard University Bullard Fellowships in Forest Research...............163

MicroMorph........................................................................................163

Courses/Workshops

Experience in Tropical Botany.............................................................165

Reports and Reviews

Armen Takhtajan – In Appreciation of His Life. Raven, Peter H.and

Tatyana Shulkina..................................................................166

Thoughts on Vernon I. Cheadle. Evert, Ray F. and Natalie W. Uhl.....171

Books Reviewed in this Issue

............................................................................176

Books Received

....................................................................................................183

Botany 2011

.........................................................................................................184

150

Plant Science Bulletin 56(4) 2010

P

LANT

S

CIENCE

B

ULLETIN

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to:

Botanical Society of America

Business Office

P.O. Box 299

St. Louis, MO 63166-0299

E-mail: bsa-manager@botany.org

Address Editorial Matters (only) to:

Marshall D. Sundberg, Editor

Dept. Biol. Sci., Emporia State Univ.

1200 Commercial St.

Emporia, KS 66801-5057

Phone 620-341-5605

E-mail: psb@botany.org

ISSN 0032-0919

Published quarterly by Botanical Society of America, Inc., 4475 Castleman Avenue, St. Louis,

MO 63166-0299. The yearly subscription rate of $15 is included in the membership dues of

the Botanical Society of America, Inc. Periodical postage paid at St. Louis, MO and additional

mailing office.

News from the Society

BSA Awards

One of the most important aspects of BSA

membership is having the opportunity to award

peers and/or student members for outstanding

efforts in support of our mission via the Society

awards program. To access the award

information, please go to

www.botany.org/

awards/

.

Please take the time to use this valuable benefit

over the next few months as we ask for

nominations for the 2011 awards. Promoting

botany and botanists is your privilege and

responsibility.

Awards Open through March 15, 2011

-Merit Award

-Charles E. Bessey Teaching Award

-Grady L. Webster Structural Botany

Publication Award

-John S. Karling and the BSA Graduate Student

Research Awards

-Undergraduate Student Research Awards

-Genetics Section Graduate Student

Research Awards

-Young Botanist Awards

Awards Open through April 1, 2011

-Jeanette Siron Pelton Award in Experimental

Plant Morphology

Editorial Manager for Plant Science Bulletin is

now live. To submit manuscripts for

consideration please go to:

http://

www.editorialmanager.com/psb/.

We

encourage all of the membership to register

as potential manuscript reviewers by visiting

that site and clicking on “Update My

Information.” This is especially important for

members of the Teaching, Historical, and

Economic Botany sections who are under-

represented in the current AJB reviewer data

base.

We also encourage all members of the society

to consider nominating individuals for the

various society and sectional awards listed on

the facing page. It is important to recognize

botanical colleagues for the fine work they do

and especially to support younger botanists in

the early stages of their careers. If you search

previous issues of PSB (it is searchable on the

BSA web site) for previous award winners, you

will notice that certain schools and certain

nominators are consistently recognized. It

may be that we have only a few star programs,

but it is more likely that this pattern results from

a relatively few individuals committed to

promoting botany at their institutions. Become

one of the few! Botany needs you!

In this issue we recognize two eminent

botanists who were leaders in the field, the

systematist Armen Takhtajan and the

anatomist Vernon Cheadle. In both cases the

authors go beyond the botany to provide

interesting perspectives of the life situation

and personal character of these inspiring

botanists. Read and enjoy.

-the Editor

151

Plant Science Bulletin 56(4) 2010

Editorial Committee for Volume 56

Nina L. Baghai-Riding (2010)

Division of Biological and

Physical Sciences

Delta State University

Cleveland, MS 38733

nbaghai@deltastate.edu

P

LANT

S

CIENCE

B

ULLETIN

Jenny Archibald (2011)

Department of Ecology

and Evolutionary Biology

The University of Kansas

Lawrence, Kansas 66045

jkarch@ku.edu

Root Gorelick (2012)

Department of Biology

Carleton University

Ottawa, Ontario

Canada, K1H 5N1

Root_Gorelick@carleton.ca

Elizabeth Schussler (2013)

Department of Ecology and

Evolutionary Biology

University of Tennessee

Knoxville, TN 37996-1610

eschussl@utk.edu

Christopher Martine

Department of Biology

State University of New York

at Plattsburgh

Plattsburgh, NY 12901-2681

martinct@plattsburgh.edu

-Darbaker Prize in Phycology

Student Travel Awards for Botany &

Economic Botany 2011, Open through April

10, 2011

-Vernon I. Cheadle STA

-Triarch “Botanical Images” STA

Section Student Travel Awards

-Pteridological Section & American

Fern Society

-Developmental & Structural Section

-Ecological Section

-Genetics Section

-Mycological Section

-Phycological Section

-Phytochemical Section

BSA Corresponding Members Outside of the

award program, the Botanical Society is active

in honoring Botanists where ever possible.

The most prestigious form this takes is when

a member like you nominates an overseas

colleague as a BSA Corresponding Member.

For many years this honor was limited to 50

people but in 2006, the Society removed this

limit to make it more available to deserving

international botanists. Corresponding

membership in the BSA is an internationally

recognized honor, and is particularly important

today with the ease in building relationships

in a virtual world. Please take the time to

consider nominating your international

colleagues for the important distinction of being

a BSA Corresponding Member. For details

s e e :

w w w . b o t a n y . o r g / a b o u t _ b s a /

corresponding_members.php

Good Green Teaching

Colleagues

The 2009 BSA Education Summit report,

available at:

http://www.botany.org/bsa/membership/

council2010/DAL-Education.pdf

The Education Summit was conceived as a

way to gain better perspectives on the various

education activities in the BSA and to parse the

BSA education objectives into the best hands

to ensure that progress is made. Based on the

Strategic Plan that is guiding the future of the

BSA, we focused on what we can and should

do to meet the goals that have been established.

We also discussed the roles of the different

education-oriented entities in the BSA and

developed action plans to achieve the goals

that we established. Below, these action plans

are developed as recommendations.

The strategic plan emphasizes that the BSA

should seek to provide botany resources for

teachers. We concurred and discussed the

best ways to meet this plant information

expectation. To meet the goal of locating and

engaging BSA experts who can contribute facts

and information about plants, we noted that the

plans for the new Membership Directory will

include opportunities to collect and display

such information about members. The

Directory will be searchable for membership

expertise.

To gather information about experts who will

identify gaps in existing instructional materials,

we recommend developing a new box on the

152

Plant Science Bulletin 56(4) 2010

abstract submission form for the annual

meeting. This box would solicit information

from “experts” on the nature and progress on

the “broader impacts” component of funded

research projects. We reasoned that BSA

members with active, well supported research

programs would be the ones with the “broader

impacts” statements and plans. With

information about ongoing activities, we should

be able to discover what ongoing education

projects might be made more public and could

provide topics for education symposia and

workshops at the annual meeting. This will

also meet the goal of fostering collaboration

among BSA members to share information

and ideas about education initiatives.

Claire Hemmingway guided a discussion of

PlantingScience progress and new objectives.

She noted that summer institutes, held at Texas

A&M University, provided opportunities for

exploring active learning activities and

conducting focus groups with teachers to help

them implement these active learning

possibilities. She also discussed expanding

the roles of mentors in helping to initiate and

conduct experiments with teachers and

students, and she introduced how video clips

153

Plant Science Bulletin 56(4) 2010

were helping teachers gain a better

understanding of some concepts and

methods. Claire provided information about a

goal of the PlantingScience program to help

teachers learn how to cover the field of biology

using plants (“Planting across the

curriculum.”). Assessment of the program is

essential, but has been challenging and is still

an elusive ultimate goal. She noted that

questionnaires provided to participants as well

as Pre-and Post testing of students was

involved as was tracking teachers and their

successes with the program in their classes.

Carol Stuessey has been the point person in

developing a plan to develop meaningful and

effective assessment of the program so that its

contributions can be fully demonstrated. We

strongly encouraged progress on this

important component of PlantingScience so

that the program could have more promise of

integration with state standards and testing.

We also noted that continued and expanded

funding for PlantingScience was likely to

depend on well-documented and analyzed

evidence of its effectiveness.

Bill Dahl reported on recent discussions in

Washington, DC involving the Obama

administration’s response to the current

nationwide scientific literacy crisis. Politicians

are seeking ways to generate more science

teachers who will incorporate more inquiry

methods in student learning. Interdisciplinary

society participation has been sought through

the coordination of fields and programs

represented by members of the Council of

Scientific Society Presidents. This group is

pushing plans for a “Science Week” program

to highlight progress and goals for future

science education.

We discussed options for developing outreach

by BSA professionals to students in their local

city and regional neighborhoods, and that this

has been supported in some instances by

NSF funding. We noted that such outreach

might be best targeted at making connections

between 4-year colleges and the Community

Colleges where an offer of expertise is likely to

be well received. We recommended

establishing information on the membership

form to ask whether individuals would be open

to inquiries from their community to answer

science questions and serve in an “Ask a

Botanist” capacity. The BSA could function as

a clearinghouse and communication hub for

making such connections. These connections

might also lead to more community college

professionals seeking membership in the

BSA. We also noted that the BSA may be able

to serve as a place for certifying the quality of on-

line courses, helping students know which

courses will provide the education outcomes

that they seek.

Chris Martine discussed his success in

establishing a student chapter of the BSA,

getting students involved with neighborhood

activities and involving them in service to the

community. We recommend having a

workshop on student chapters at the annual

meeting.

We considered it to be a valuable BSA

contribution for us to develop assessments of

teaching modules, but we wondered how to

generate funding for such assessments. We

already have some PlantingScience modules

and curricula that meet some state standards

and the goals of assessment tests of students.

But we need more of them for teachers to use

as well as for the education of new teachers

(pre-service training).

We recommended building on the fine work of

Chris Martine, who has developed videos to

inform children about aspects of science in

general and botany in particular. To develop

this agenda, we recommend providing

opportunities at our annual meeting to conduct

video interviews with experts attending the

meeting. Not only would this help to explore

topics that might be expanded into new video

segments, but it would also discover which

BSA colleagues are ideally suited for this video

medium, and whose research might be used

to illustrate science principles and practices.

We might also be able to develop “How To”

videos of various techniques and procedures.

We devoted some discussion to the opportunity

for certification of individuals as “Botanists.”

We concluded that we need to review the

competencies necessary to be certified.

Robynn Shannon commented that the

Ecological Society of America has developed a

certification program and we might be able to

learn from their efforts and adopt some of their

154

Plant Science Bulletin 56(4) 2010

BSA Science Education

News and Notes

methods. We recommended forming a

committee to explore these options and

develop recommendations that would be

reviewed by the Education Committee and

ultimately forwarded to the Board of Directors

for discussion and implementation. Members

of that exploration committee could include

Marsh Sundberg (who has been working with

the National Forest Service to develop a

certification option), Robynn Shannon, Krissa

Skogen, and Bill Dahl.

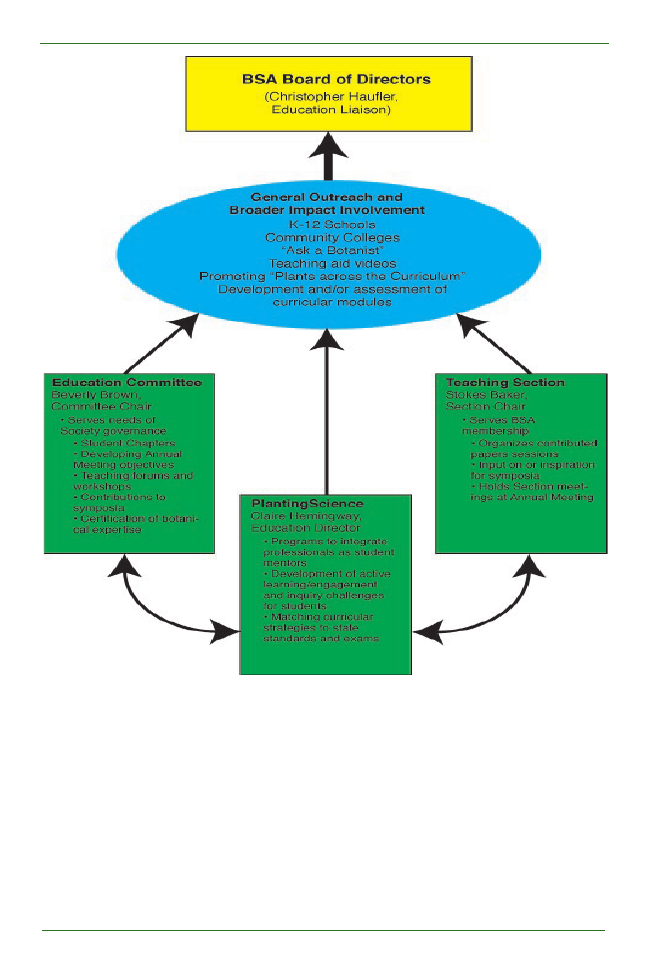

Through the meeting, we devoted time and

thought to exploring and defining the roles of

the Education Committee and the Teaching

Section of the BSA. After considerable

discussion, we concluded that the Education

Committee meets the governance function in

education for the BSA, i.e., implementing the

educational mission of the BSA and

recommending policies that will help the BSA

achieve its education mission. Thus, the

Education Committee would be charged with

organizing society-wide education initiatives

at annual meetings (such as opportunities for

workshops and forums on education). The

Teaching Section would function to serve the

members of that section, by organizing

contributed papers sessions and symposia of

interest to those members. Thus, both the

Education Committee and the Teaching

Section provide vital and complementary

contributions to the BSA and its members. We

recommend that special attention be paid to

appointing Education Committee members

so that those interested in meeting BSA

education goals will be involved and we

recommend appointing a member of the

Teaching Section as an ex officio member of

the Education Committee. Normally, this

would be the Chair of the Teaching Section, but

another individual may be appointed as

appropriate.

We note that the we are working toward

achieving the strategic goals established by

the BSA strategic planning committee and we

are now poised to have a better sense of how

to coordinate and develop cooperation among

the various components of the BSA that

address education aspects of the Society.

I personally thank the members who took time

out of their obviously busy schedules to attend

this Summit and contribute their expertise and

perspectives on education and the BSA. We

certainly had a productive and valuable meeting

that should translate in an improved and

invigorated education mission of the BSA.

Respectfully submitted,

Chris Haufler, Board of Directors Member

associated with BSA education

BSA Science Education News and Notes is a

quarterly update about the BSA’s education

efforts and the broader education scene. We

invite you to submit news items or ideas for

future features. Contact: Claire Hemingway,

BSA Education Director, at

chemingway@botany.org

or Marshall

Sundberg, PSB Editor, at

psb@botany.org

.

PlantingScience — BSA-led student research

and science mentoring program

PlantingScience Online Mentored Inquiry

Session.

“We posted our research question on our wall

and we are ready to get to work.”

“Hello!! I can’t wait to meet the mentors and start

this project. I’m not very good with science so

hopefully I will learn a few new things!!”

“… Plants are so interesting at first i didnt think

i would like this class but the more i got into it the

more i liked it! … We posted our ideas for our

experiment. Let us know what you think!”

“We have everything in order for our experiment.

I’m getting excited I can’t wait to find out how it

turns out. Maybe then I can get the answer I’m

searching for. Does moisture in the soil affect

plant life? Well the research will tell all soon

enough”

Students share their excitement with scientist

mentors as the fall 2010 session kicks off. By

the time the online session ends in November

we expect 25 schools from 14 states across the

155

Plant Science Bulletin 56(4) 2010

nation to take part, including 4 middle schools,

20 high school classes, and one university.

This session marks the largest array of inquiry

modules available (the Wonder of Seeds—

seed germination and seedling growth; Power

of Sunlight—photosynthesis and respiration;

Foundations of Genetics—traits, variation, and

environment in Rapid Cycling Brassica) and in

field testing (Where does pollen come from?—

pollen and pollination; Celery Challenge—

osmosis, diffusion, and transpiration; C-Fern®

in the open—sexual reproduction and

alternation of generations).

Thanks to the many students, teachers,

mentors, and societies whose contributions

make PlantingScience a vibrant online learning

community! Each fall and spring

PlantingScience offers a two-month window of

opportunity for student-teacher-scientist

interactions during an online mentored inquiry

session. Each academic year, the Botanical

Society of America and the American Society of

Plant Biologists sponsor members of the

Master Plant Science Team, a cohort of mainly

graduate students and post-doctoral

researchers who make an extra time

commitment to mentoring in both sessions.

And each year the program continues to grow

and partnerships among collaborating

organizations strengthen.

Congratulations to the 2010-2011

PlantingScience Master Plant Science Team!

The Botanical Society of America is pleased to

sponsor: Lorraine Adderly, Rob Baker, Kate

Becklin, Amanda Birnbaum, Angelle Bullard-

Roberts, Katie Clark, Rafael de Casas, Morgan

Gostel, Melissa Gray, Eric Jones, Allison

Kidder, Hayley Kilroy, Laura Lagomarsino,

Chase Mason, David Matlaga, Arijit

Mukherjee, Kelly O’Donell, Taina Price, Emily

Sessa, Kate Sidlar, and Lindsey Tuominen.

The American Society of Plant Biologists is

pleased to sponsor: Robert Barlow, Erica

Fishel, Betsy Justus, Sasha Ricaurte, Kaiyu

Shen, and Madhura Siddappiji.

Welcome to the Canadian Botanical Society

joining this fall as partner society. The individual

contributions of the >400 volunteer mentors

and the collaboration among >14 scientific

societies and organizations makes

PlantingScience an unprecedented effort to

connect science experts with classrooms and

support botanical literacy. What a phenomenal

response to Dr. Bruce Albert’s 2003 call to the

BSA for scientists to meaningfully engage with

K-12 education to address science literacy!

We invite you to follow fall student projects in the

Research Gallery at

www.PlantingScience.org

.

After a short winter break, the spring 2011

session will run from 14 February to 15 April

2011. Please join us again this spring to spark

students’ enthusiasm for investigating science

and plants.

USA Science and Engineering Festival.

A celebration of science is taking place with the

aim of reinvigorating our nation’s youth in

science, technology, engineering, and math.

The USA Science & Engineering Festival

highlight is an expo on the National Mall in

Washington DC on October 23 & 24. Executive

Director Bill Dahl and BSA members staffed

booth 1006 in the Andrew W. Mellon Auditorium

to share the excitement of PlantingScience

and society happenings with festival

participants.

http://www.usasciencefestival.org/

Science Education Bits and Bobs

Reports Tracking College Readiness to

Completion — Several recent reports and

programs address segments of the pipeline

issue with a focus around the critical college

years. Readers will find a mixture of hopeful

and disheartening statistics. A common finding

is that how students are prepared for college

through their high school classes makes a

difference.

2010 College-Bound Seniors Who Take Core

Curriculum Score Higher on SAT. The College

Board reports record-breaking number of

students in the class of 2010 took the SAT, and

they provide data showing a clear effect of

rigorous high school coursework on student

SAT results.

http://www.collegeboard.com/press/

releases/213182.html

Mind the Gaps: How College Readiness

Narrows Achievement Gaps in College Success

by ACT finds that high school course work, both

core curriculum and additional science and

156

Plant Science Bulletin 56(4) 2010

math courses, are significant factors related to

college success. The report also describes

contributions of high school indicators to

improving college success among

underrepresented minority students and

economically disadvantaged students.

h t t p : / / w w w . a c t . o r g / r e s e a r c h /

policymakers/reports/mindthegaps.html

Taking the Next Step: The Promise of

Intermediate Measures for Meeting By Jobs for

the Future reinforce the importance of data,

data, and data in documenting and

understanding the pathway from pre-college

coursework to college degree completion. Key

milestones, multi-institutional projects, and

the importance of institutional support for data

use are discussed.

http://www.jff.org/publications/

e d u c a t i o n / t a k i n g - n e x t - s t e p - p r o m i s e -

intermediate-me/1136

Finishing the First Lap: The Cost of First Student

Attrition in America’s Four Year Colleges and

Universities by American Institutes for

Research reports that nationwide 30% of first-

year college students do not continue. This

high dropout rate has enormous implications

for the students’ lives and cost state and federal

taxpayers over $9 billion for appropriations to

higher education.

h t t p : / / w w w . a i r . o r g / n e w s /

index.cfm?fa=viewContent&content_id=989

To compare graduation rates or cost per degree

among colleges or across US States, visit the

College Measures interactive website, which

draws on Finishing the First Lap report:

http://collegemeasures.org/

The Community College Link to Degrees and

Careers — Community colleges have

traditionally served as important conduits for

diverse student populations seeking a four-

year degree or place in the workforce. The role

of community colleges has received additional

attention and funding from the local to the

national level.

Learn about the White House’s initiative Skills

for America’s Future to improve partnerships

between community colleges and businesses.

http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/

2010/10/04/building-skills-america-s-future

Read a perspective of meeting challenges

through 2-year and 2-year college

collaborations.

George Boggs 2010. Growing Roles for Science

Education in Community Colleges. Science

329: 1151-1152

Editor’s Choice

Bean, T.E., G.M., Sinatra, and P.G. Schrader.

2010. Spore: Spawning Evolutionary

Misconceptions? Journal of Science Education

and Technology 19(5):409-414.

The authors examine how evolutionary content

is depicted in the video game Spore and offer

teaching strategies to address misconceptions

that may be reinforced through computer

simulations.

Dewprashad, Brahmadeo. 2010. More to the

Color of Roses than Meets the Eye. Journal

of College Science Teaching 40: 66-69.

This organic chemistry demonstration can

easily be adapted to introductory botany,

horticultural botany, or economic botany

courses at the lower division college level - - as

well as K-12! Floral pigments, isolated with hot

isopropyl alcohol, are used to “paint a picture”

on a piece of filter paper. A variety of acidic and

basic solutions are then used to “develop” the

picture in multicolored hues.

Eyster, L. 2010. Encouraging Creativity in the

Science Lab: A series of activities designed

to help students think outside the box. The

Science Teacher 77(6):32-45.

This article emphasizes student ideas that

inhibit creativity and teaching tips to overcome

these and offers a seed germination and

growth chamber set up sample “solve it” activity.

Frisch, J.K., Unwin, M.M., and George W.

Saunders. 2010. Name that Plant!

Overcoming Plant Blindness and Developing

a Sense of Place Using Science and

Environmental Education. In A. M. Bodzin et al.

(eds.) The Inclusion of Environmental

Education in Science Teacher Education, Part

2: 143-157.

This book chapter takes up Wandersee and

Schussler’s cause of addressing plant

blindness. Ideas for nature-based outdoor

157

Plant Science Bulletin 56(4) 2010

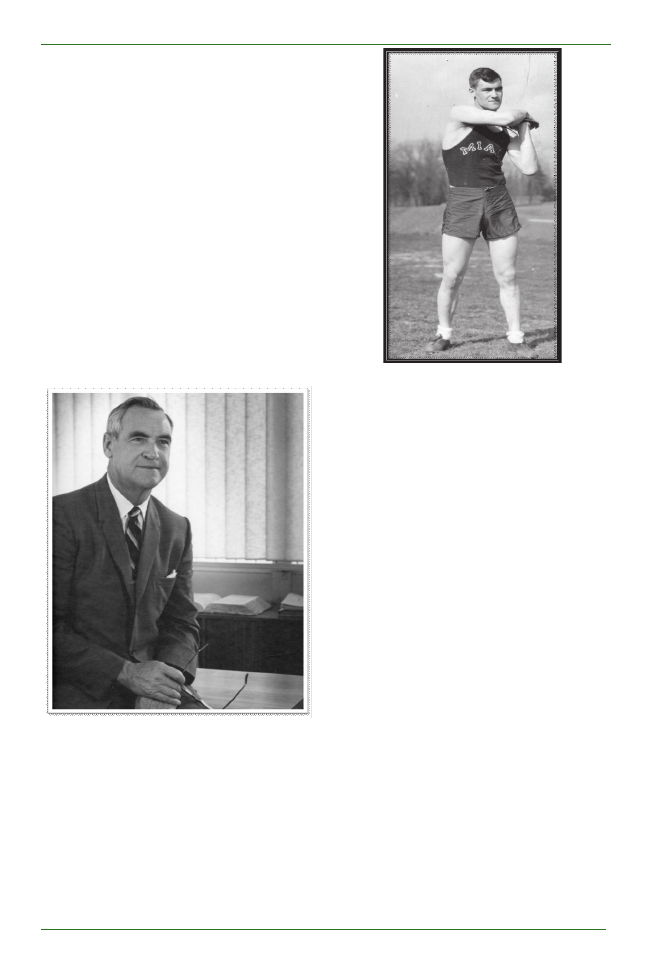

Lawrence Joseph Crockett

(1926-2010)

The City College of New York lost one of its

most beloved teachers last spring. Professor

Emeritus Lawrence J. Crockett died of

complications of Parkinson’s disease and

cancer on June 8, 2010 in San Antonio, TX.

Larry Crockett was born in Brooklyn, New York

on September 3, 1926. He attended Columbia

College as an undergraduate on a scholarship,

and earned his degree in 1949. Following

service in Korea in the early 1950s, he

continued his studies at Columbia, this time

as a graduate student under Dr. Edwin B.

Matzke, earning his MA (1954) and PhD (1958).

1

His first publication, A Study of the Tunica

Corpus and Anneau Initial of Irradiated and

Normal Stem Apices of Nicotiana Tabacum L,

appeared in the Torrey Botanical Society’s

Bulletin in 1952

2

. In 1958, he authored a study

on the irradiated stem apex of Coleus blumei.

2

Subsequent research on the same species

resulted in another paper in the American

Journal of Botany.

3

His interest in the unusual

resulted in yet another paper, this time on

Stylites

4

. During that time he also taught botany

at Barnard College (1955-1959). From 1959-

1961 he taught botany at Fairleigh Dickinson

University in New Jersey. Larry joined the faculty

of the Biology Department of The City College

of New York (CCNY) in 1961, where he taught

courses in vascular and nonvascular plants in

addition to field botany. When the CCNY Urban

Landscape Program was introduced he also

taught budding landscape architects in a

course specifically designed for them. While at

CCNY he served as a member of the school

Senate from 1968-1971, as Deputy Chairman

of the Biology Department from 1969-1972,

and was also a member of the Faculty Council

from 1968-1969.

Crockett was a member of the Botanical Society

of America (BSA) and served for many years as

Business Manager (1961-1972) of the

American Journal of Botany (AJB) and also as

Business Manager (1961-1964) of the Plant

Science Bulletin (PSB). From the early 1960’s

to the mid 1970s he served the BSA as a

member of the editorial board of the AJB and

In Memoriam

experiences for K-12 classes are offered.

Ilkorucu-Gocmencelebi, S. and M. Seden Tapan.

2010. Analyzing students’ conceptualization

through their drawings. Procedia Social and

Behavioral Sciences 2: 2681-2684.

Less than 45% of fifty preservice primary teachers

in Turkey asked to draw a flower as part of a study

on assessing student conceptualizations were able

to label the flower correctly. The authors also report

that flowers that were drawn more accurately were

also more comprehensively labeled.

Kazilek, C. 2010. Ask A Biologist: Bringing

Science to the Public. PLoS Biology 8(10):

e1000458. Doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000458

Dr. Biology’s Pocket Seed Viewer, an online collection

of data, images, and animations that support student

investigations of seed germination, is featured in this

review article about the Ask A Biologist website.

Mentors and teachers who have students

investigating the PlantingScience Wonder of Seeds

module may find seed information both the Eyester

and Kazilek articles of interest.

Morris, Amy. 2010. Investigation of Essential

Oils as Antibiotics. The American Biology Teacher

72: 499-500.

Traw, M. Brian and Nancy Gift. 2010. Environmental

Microbiology: Tannins & Microbial

Decomposition of Leaves on the Forest Floor.

. The American Biology Teacher 72: 506-511.

These two articles in the October issue illustrate two

plant applications of the traditional “antibiotic disk”

experiment used in microbiology. The second has the

advantage of having students produce their own

extracts for testing against bacteria. The first follows

up on several recent reports of the antibiotic properties

of spices, especially those in use in the cuisine of hot

climates.

Thompson, S. 2010. Classroom Terraria:

Enhancing Student Understanding of Plant-

Related Gas Processes. Science Scope 33(8):20-

26.

This article addresses common student conceptions

about plants through extended observations following

initial middle school student speculations about what

will happen to a plant sealed in a jar.

See Ecological Restoration Volume 28, Number 2,

June 2010 for a special theme on education and

outreach in ecological restoration.

View all titles in JNRLSE Volume 39 at

http://

www.jnrlse.org/issues

158

Plant Science Bulletin 56(4) 2010

the PSB. He was an active member of the

Torrey Botanical Club (now the Torrey Botanical

Society), serving as its president twice (1970,

1985), and regularly organizing programs for

its members. He also wrote twenty articles,

several of them in two parts, entitled “On the

Trail of John Torrey” which highlighted

significant achievements and episodes in the

life of one of America’s most celebrated early

botanists. All were published in the Bulletin of

the Torrey Botanical Club.

5

In addition, he

coauthored several papers and presentations

with other noted scholars.

6,7.

Over the years his

work has been cited many times by numerous

researchers. Larry also served on the Steering

Committee for the Centennial Celebration of

the New York Botanical Garden. He authored

“Wildly Successful Plants: a Handbook of North

American Weeds”, published in 1977 and

recently reprinted. In 1989 he appeared twice

on Cable TV on the interview program

WORLDWISE, speaking on the topic of

“Evolution of Photosynthesis and its Effects on

the Living World” and, on a later show, on

“Seeds and Civilization.”

Above all, Larry loved teaching, and it was as a

teacher that Larry might have made his most

valuable contribution to biology and his

students. His enthusiasm for botany was

infectious, and stimulated many who had

resisted even taking a botany course into

making it their life’s work. One of us (LBK)

recalls begging the dean at CCNY to waive the

botany requirement because she saw no

relevance to her major in Zoology. His wise

refusal of her request became a turning point

in her career as she became mesmerized by

Professor Crockett’s lectures and devoted her

future to Plant Biology. Another of us (ESC)

became a horticultural librarian. Yet another

(ML) is on the faculty of the University of Texas

at San Antonio. Larry was an absolutely

spellbinding lecturer. Many of his students

have gone on to become well known

researchers, and some became members of

the National Academy of Science. He received

the Charles Edwin Bessey Teaching Award

from the Botanical Society of America in 1984

and won the Outstanding Teacher Award of

CCNY in 1988. Larry was also so honored by

the American Association for Higher Education

in 1989. He managed to meld botany and

history in a way that brought new life to both. His

writings on the flora of the Unicorn tapestries at

the Cloisters of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

in New York City brought him international

recognition, and are just two examples of

Larry’s ability to connect science with art

8,9.

It

comes as no surprise that he was once a

member of the Renaissance Society of

America. He was a true Renaissance man,

and an accomplished scholar of the history of

science as well as botany.

Other examples of his talent for melding history

with botany took the form of writing and acting

in plays about noted scientists. His “Market

Day in Delft: An Hour with Henry Oldenburg and

Antony van Leeuwenhoek” and “An Evening

with John Torrey” were produced at many

universities and professional meetings,

including the International Congress of

Protozoology, the BSA, the New York

Microscopical Society, as well as on the campus

of CCNY. BSA members may recall our current

PSB editor, Marshall Sundberg, as he played

Henry Oldenburg opposite Larry’s

Leeuwenhoek at the American Institute of

Biological Sciences meeting in Knoxville, TN,

in August 1984. Perhaps the only play which he

wrote and in which he performed that did not

touch upon his botanical interests was

Alexander VI: The Bull of the Borgias. It was

Lawrence J. Crockett (ca. 1970) at

Brookhaven National Laboratories

159

Plant Science Bulletin 56(4) 2010

performed several times for various audiences,

but most memorably for the public at the

Cathedral of St. John the Divine in upper

Manhattan in the early 1970’s. The noted drama

critic for The New York Times, Clive Barnes,

attended the performance and reviewed it very

favorably in that newspaper, which

Larrycherished for many years.

What was it like to be a student of Dr. Crockett?

Enrolling in Field Botany at CCNY meant

enrolling in a never-to-be-forgotten adventure.

When, during the first meeting of the field

botany class, he informed us that over the

course of the semester we would learn to

recognize and name about 500 plants, we sat

in disbelief. But he was right. Local botanical

gardens and beaches, New York State bogs,

the New Jersey Pine Barrens, the Sharon

Audubon Nature Sanctuary in Connecticut, even

New York City’s own Central Park were all fair

game for Larry’s weekly field trips. Rain or

shine we tramped through mud, sand, and dirt,

and occasionally fell into one of the quaking

bogs that brought botany to life for us.

When we weren’t wading through surf grabbing

pieces of algae and learning about

Rhodophyta, or marveling at a tiny Drosera or

the walking fern, Asplenium rhizophyllum, we

were trying (in vain) to keep up with Larry as he

plunged ahead into yet another of Nature’s

collections of local plants. Specimens gathered

were passed back from the front of the often

single-file column to those bringing up the

rear, by which time the plants looked very sorry

indeed. All were carefully collected in plastic

bags and reexamined as we took our buses

and subways back home at the end of the day.

But he was right – we did learn the scientific

names of close to 500 species – and remember

most of them to this day. Even now, when

purchasing plants at local nurseries, it’s likely

that most graduates of his course still ask for

composites, grasses, trees, shrubs, etc., by

their scientific name before buying them; daisy,

foxtail, oak or beach plum simply won’t do.

We can think of no greater tribute to a teacher

than the letter found in his CCNY file from Paul

Friedberg, the Director of what was then the

CCNY Urban Landscape Program:

“...students…would move mountains and

perform incredible feats to get into your class.

Furthermore, when I indicated [to them] that you

would be teaching the Plant Materials course

directly for the Landscape Program, there was

a roar of approval and delight...one or two

students that have already had the course said

they felt cheated...” Likewise, Karl J. Niklas, a

past Editor-in-Chief of the AJB and a past

president of the Botanical Society of America,

said of Larry “He was the most splendid teacher

and kindest human being I’ve ever known. He

inspired generations of students to follow in his

footsteps. I should know. I was one of them!

Those of us who had the privilege of having him

as an instructor will always cherish our

memories of his fabulous lectures and the

warmth of his personality. He made us want to

become botanists and teachers by virtue of his

boundless exuberance and obvious delight in

the study of plants”.

Larry was cared for in his last years by his

former student and great friend, Michael

Laverde, and is also survived by his former wife,

Edith Crockett. He will be deeply missed. A

website has been set up to which friends and

former students may post their remembrances,

both personal and professional. The name of

the site is www.larrycrockettinmemoriam.org,

and this tribute will be the first posting. Please

send what you would like to have posted on the

website to: edith@waterfordconnection.com.

The site will remain active for two years and its

contents archived at the Hunt Institute for

Botanical Documentation in Pittsburgh, PA.

Edith S. Crockett, The Waterford Foundation,

Waterford, Virginia

Jane Gallagher, The City College of New York,

City University of New York

Lee B. Kass, Cornell University

Michael Laverde, The University of Texas at San

Antonio

(End notes)

1 Crockett, Lawrence J. Zonation and Tunica Corpus

Relationships in the Stem Apex of Coleus blumei,

Benth., Before, During, and After Irradiation with

Cobalt-60. PhD thesis, Columbia University, 1958.

2 Crockett, Lawrence J. In: Bulletin of the Torrey

Botanical Club, 1957, Vol. 84(4):229-236.

3 Crockett, Lawrence J. Effects of Chronic Gamma

Radiation on Internal Apical Configurations of

Vegetative Shoot Apex of Coleus Blumei. American

160

Plant Science Bulletin 56(4) 2010

Personalia

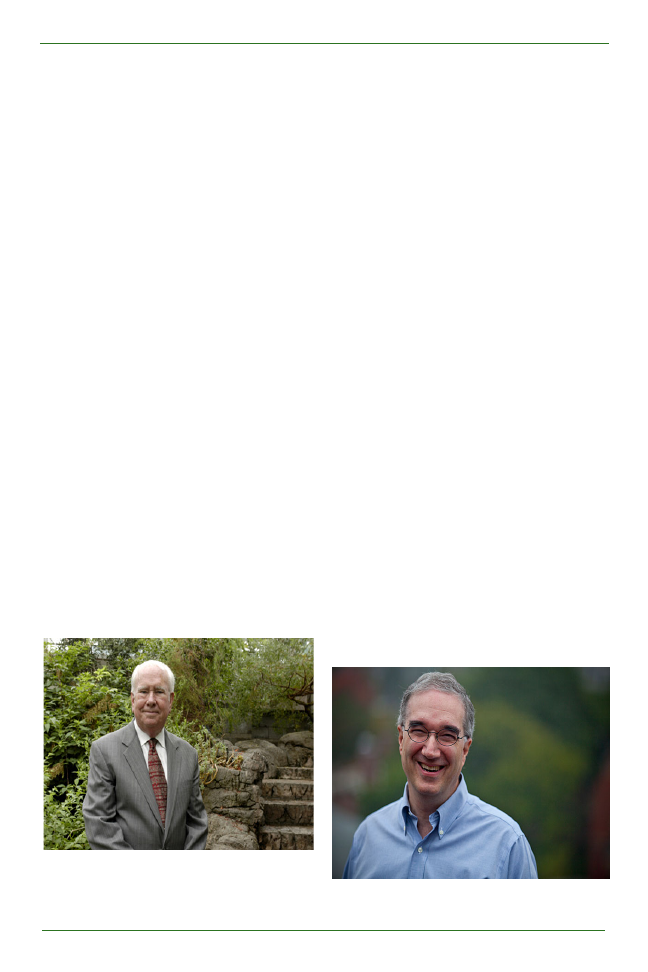

Dr. Peter Raven receives the

William L. Brown Award for

Excellence in Genetic Resource

Conservation

Friedman named Director of the

Arnold Arboretum

Evolutionary biologist to join Faculty of

Arts and Sciences

William “Ned” Friedman has been named the

new director of the Arnold Arboretum. He also

will be a professor in the Faculty of Arts and

Sciences. On Nov. 4, Friedman will deliver a

lecture at the Harvard Museum of Natural History

on “Darwin’s ‘Abominable Mystery’ and the

Search for the First Flowering Plants.”

William “Ned” Friedman, an evolutionary

biologist who has done extensive research on

the origin and early evolution of flowering plants,

has been appointed director of the Arnold

Arboretum.

Friedman, set to start on Jan. 1, will be the

eighth director of the Arboretum, which is

Dr. Peter Raven, President Emeritus of the

Missouri Botanical Garden, has been chosen

as the 6th recipient of the William L. Brown

Award for Excellence in Genetic Resource

Conservation. The biennial award recognizes

the outstanding contributions of an individual

in the field of genetic resource conservation

and use. The award is made possible through

the generous support of the Sehgal Family

Foundation, in cooperation with the family of Dr.

William L. Brown. In choosing Dr. Raven as the

2010 winner, the award committee

acknowledges a lifetime spent working to

preserve the world’s plant resources, upon

which all life on Earth depends. Dr. Raven will

receive the award prior to his keynote address

to the 2011 meeting of the Botanical Society of

America to be held in St. Louis July 10-13, 2011.

For more information, please visit

www.WLBCenter.org/award.htm

.

Journal of Botany, 1986, 73(5): 265-268.

4 Crockett, Lawrence J. Stylites of Peru

– A Living Fossil. Garden Journal, 1967, Vol.17 (1):

26-27.

5 Crockett, Lawrence J. On the Trail of John

Torrey…Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club

, Vols. 113 – 119, 1986-1992.

6 Crockett, Lawrence J and Myron C Ledbetter

(Abstract). Association of Microtubules With Early

Wall Formation In Zoospores of Marine Alga

Cladophora gracilis. American Journal of Botany,

1970, Vol. 57 (6): 741.

7 Lee, John J, Lawrence J. Crockett, Johnny Hagen,

Robert J. Stone. The taxonomic identity and

physiological ecology of Chlamydomonas hedleyi

sp. nov. algal flagellate symbiont from the foraminifer

Archaias angulatus. European Journal of Phycology,

1974, 9(4):407-422.

8 Crockett, Lawrence J. Using Works of Art (e.g., the

Unicorn Tapestries) in Teaching.

American Journal of Botany, 1986, 73(5): 798.

9 Crockett, Lawrence J. The Identification of a Plant

in the Unicorn Tapestries. Metropolitan

Museum of Art Bulletin, 1982, 17:15-22.

161

Plant Science Bulletin 56(4) 2010

administered by Harvard’s Office of the Provost.

He also will be a tenured professor in the

Faculty of Arts and Sciences. His priorities

include strengthening ties between the

Arboretum and the Cambridge campus and

working closely with the Arboretum’s neighbors

in Jamaica Plain and Roslindale.

“Ned’s appointment underscores Harvard’s

commitment to integrating the incredible

resources and opportunities presented by the

Arboretum with the important work of our

scientists here in Cambridge,” said Provost

Steven E. Hyman. “As an FAS faculty member,

Ned will be a part of the Harvard community. As

director of the Arboretum, he will seek closer

ties, not only with our Cambridge campus, but

also with the city of Boston, the Arboretum’s

home.”

Friedman has been a professor of ecology and

evolutionary biology at the University of

Colorado since 1995. As professor of

organismic and evolutionary biology at Harvard,

he will conduct research in the new Weld Hill

Research and Administration Building at the

Arboretum and teach at Harvard’s Cambridge

campus.

Part of Boston’s Emerald Necklace of parks,

the 265-acre Arboretum, founded in 1872 and

designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, is free

and open to the public every day of the year. Its

programs and events include lectures and

community outreach initiatives in neighboring

schools.

“Professor Friedman’s appointment creates

an exciting opportunity to connect the unique

resources of the Arnold Arboretum in Boston to

the plant science research and education

occurring on our Cambridge campus,” said

Jeremy Bloxham, FAS dean of science. “Ned’s

teaching and leadership will facilitate closer

linkages between the educational and

research possibilities the Arboretum presents

and the innovative scholarship of our faculty

and students.”

Friedman’s research has focused on patterns

of plant morphology, anatomy, and cell biology.

He was recently acclaimed for his discovery of

a new type of reproductive structure in an

ancient flowering plant that may represent a

critical link between flowering plants and their

ancestors.

Friedman also has a keen interest in the history

of science, particularly the intellectual history of

evolutionism. He has designed and taught

courses on the life and work of Charles Darwin

and other historical figures, and lectured on the

subject at natural history museums and other

venues.

On Nov. 4, Friedman delivered a lecture at the

Harvard Museum of Natural History on “Darwin’s

‘Abominable Mystery’ and the Search for the

First Flowering Plants.” He plans to launch a

Director’s Lecture Series at the Arboretum that

will make accessible to the public cutting-edge

research by leading scientists from Harvard

and around the world.

“I am thrilled to be able to welcome a diverse

group of audiences to the Arnold Arboretum,

one of the world’s leading resources for the

study of plants, and help integrate it more

deeply into the research and teaching missions

of Harvard University,” said Friedman. “I am

also deeply committed to building on the

Arboretum’s robust history and its ongoing

programs to enhance a neighborhood resource

that brings the world of biodiversity to Greater

Boston.”

Friedman is the author or co-author of more

than 50 peer-reviewed publications, and serves

on editorial committees for the American

Journal of Botany, the International Journal of

Plant Sciences, the Journal of Plant Research,

and Biological Reviews. He is a member of the

Botanical Society of America.

Friedman received a bachelor’s degree in

biology from Oberlin College in 1981, and a

doctorate in botany from the University of

California, Berkeley, in 1986. He is a fellow of

the Linnean Society of London, and a 2004

recipient of the Jeanette Siron Pelton Award,

granted by the Conservation and Research

Foundation through the Botanical Society of

America. In 1991, he received the Presidential

Young Investigator Award from the National

Science Foundation. Friedman spent his early

career in the Botany Department at the University

of Georgia before joining the faculty at the

University of Colorado.

162

Plant Science Bulletin 56(4) 2010

New Non-Profit Directly Links

Donors to Researchers

Seeks Submissions from Scientists in

Need of Project Funding SciFlies.org

creates a new public funding mechanism

for science discovery and innovation

St. Petersburg, Fla. - (Sept. 24, 2010) - Scientists

and researchers seeking additional funding

sources for projects that will enhance their

research goals now have an alternative

resource for the money they need to propel

their projects forward: the general public.

SciFlies.org, a new non-profit organization

created to connect research projects with

thousands of small donors who wish to support

them directly, is now accepting submissions

from scientists and researchers. Any scientist

or researcher affiliated with a university or

research institution is invited to visit

www.sciflies.org

to register and fill out the

research application. Once a project is

submitted, it will undergo a review for scientific

merit and public readability before going live on

the site. The formal launch of SciFlies.org to

the general public will be announced in

November 2010.

“SciFlies provides one of the most significant

new avenues for funding research,

development and innovation in 50 years,” said

David Fries, co-founder and chief science

officer of SciFlies.org. “As someone who has

been writing grants and raising funds for my

research projects and those on which I¹ve

been part of a team, I know how frustrating it is

to have vital discovery and proof of concept

work held up for want of a few thousand dollars.”

Fries, who is on the faculty of the University of

South Florida¹s College of Marine Science and

has spun out several successful

entrepreneurial companies from technologies

developed there, knows all too well how a lack

of steady funding can interrupt the progress of

scientific discovery. To address this need, he

partnered with veteran nonprofit and political

fundraiser Larry Biddle and regional technology

industry advocate and communications

strategist Michelle Bauer to develop the model

for SciFlies.

The way SciFlies works is simple. Scientists

complete an application that allows them to

present their project needs and goals in terms

that the general public will understand. An

individual page on SciFlies.org is set up for

each project in categories such as medical

and environmental research so that the public

can select projects based on their personal

interest. Donors can then make direct, tax-

deductible contributions to the projects of their

choice through the site. The funds are deposited

directly into the foundation accounts of the

university or research institution with whom the

scientist is affiliated for direct disbursement

once the fundraising goal is achieved.

The funds generated from the public donors

can be used toward students, staff, equipment

or access to data or facilities that are needed

to complete the project.

“I believe that the funding mechanism SciFlies

offers will not only facilitate the advance of

research and discovery, but also change the

public perception of how scientific research

works,” Fries continued. “SciFlies will spur

more public interest in the fields of science and

technology by building meaningful

relationships between the public and scientists

who are solving the world¹s challenges.”

SciFlies handles the transfer of all gifts from

donors to the researchers¹ institutions. At this

time, individual project requests are set at a

minimum of $5,000 and will not exceed $100,000

per year. Requests that are greater than

$50,000 will require a phased approach. An

option for multi-year proposals is planned for

the future.

About SciFlies.org

SciFlies makes science happen by

accelerating research and development

projects that lead to new discoveries and

innovation. Our grassroots approach and

micro-donation model showcases vetted and

qualified research projects from across all

fields of scientific inquiry, allowing anyone,

anywhere to directly support research they care

about. SciFlies¹ goal is to foster ongoing citizen

engagement with science and technology,

Special Opportunities

163

Plant Science Bulletin 56(4) 2010

Harvard University

Bullard Fellowships in Forest

Research

Each year Harvard University awards a limited

number of Bullard Fellowships to individuals

in biological, social, physical and political

sciences to promote advanced study, research

or integration of subjects pertaining to forested

ecosystems. The fellowships, which include

stipends up to $40,000, are intended to provide

individuals in mid-career with an opportunity to

utilize the resources and to interact with

personnel in any department within Harvard

University in order to develop their own scientific

and professional growth. In recent years

Bullard Fellows have been associated with the

Harvard Forest, Department of Organismic

and Evolutionary Biology and the J.F. Kennedy

School of Government and have worked in

areas of ecology, forest management, policy

and conservation. Fellowships are available

for periods ranging from six months to one year

after September 1

st

. Applications from

international scientists, women and minorities

are encouraged. Fellowships are not intended

for graduate students or recent post-doctoral

candidates. Information and application

instructions are available on the Harvard Forest

web site (

http://harvardforest.fas.harvard.edu)

.

Annual deadline for applications is February

1

st

.

building meaningful relationships between

the public and scientists working to solve the

world¹s medical, environmental, engineering,

and other challenges.

For more information, visit

www.sciflies.org.

Dear colleagues,

microMORPH is pleased to announce a funding

opportunity for graduates students,

postdoctorals, and assistant professors in

plant development or plant evolution. $3,500 is

available to support cross-disciplinary visits

between labs or institutions for a period of a few

weeks to an entire semester. We are

particularly interested in proposals that will

add a developmental perspective to a study of

evolution of populations or closely related

species. We are also interested in

developmental studies that will incorporate the

evolution of populations or closely related

species. The deadline for proposals is

December 15th, 2010. More information about

the training grants and the application process

may be found on the microMORPH website:

http://www.colorado.edu/eeb/microMORPH/

grantsandfunding.html

These internships are supported by a five-year

grant from the National Science Foundation

entitled microMORPH: Molecular and

Organismic Research in Plant History. This

grant is funded through the Research

Coordination Network Program at NSF. The

overarching goal of the microMORPH RCN is

to study speciation and the diversification of

plants by linking genes through development

to morphology, and ultimately to adaptation

and fitness, within the dynamic context of natural

populations and closely related species.

164

Plant Science Bulletin 56(4) 2010

The microMORPH RCN promotes and fosteres cross-disciplinary training and interaction

through a series of small grants that allows graduate students, post-doctoral researchers, and

early career faculty to visit labs and botanical gardens as well as attend scientific meetings.

Award Amount

Each Year, microMORPH is able to fund five graduate student, post-doctoral, or early career

faculty cross-training research opportunities for up to $3,500 to cover travel, lodging, and pier

diem.

Evaluation

The next microMORPH Cross Disciplinary Training Grant Deadline is December 15th, 2010.

Evaluation of grants begins the day after they are due. Submissions are accepted until all annual

funds have been committed.

Application Materials

1) A letter from the prospective host lab (indicating a willingness to host consensus about the

proposed activities of the visitor, and an explicit statement acknowledging that the host lab

understands that the microMORPH RCN funds may not be used to underwrite the proposed

research activities).

2) A letter from the Applicant detailing research plans and interaction

3) A proposed budget for travel costs, per diem, lodging, and meals.

Each letter must be no more than three pages. The applicant letter must specifically document

the fact that the training opportunity is cross-disciplinary between an organismic and a molecular

laboratory studying plant developmental evolution. By NSF rules, the budget may not be used to

directly fund costs associated with the proposed research activities (e.g., supplies).

How to Apply

All application materials must be emailed as attached .pdf or Word documents to William (Ned)

Friedman,

ned@colorado.edu

.

Proposal Evaluation

Two members of the steering committee (one organismic and one molecular) and a third

individual from outside the core participants (chosen by the steering committee) are charged with

evaluating applications.

165

Plant Science Bulletin 56(4) 2010

Experience in Tropical Botany

Harvard University Summer School, in

collaboration with The National Tropical

Botanical Garden announces the following

course in 2011.

Dates: June 1 – June 30 2011

Location: The Kampong Garden of the National

Tropical Botanical Garden,

4013 Douglas Road, Coconut Grove,

Miami FL 33133

The Class will use the newly-constructed

Kenan Teaching Laboratory at The Kampong

(wet bench and microscope facilities) and be

accommodated at the comfortable Tyson

dormitory (of Scarborough House) on the same

property.

Course title: Biology S-111. “Biodiversity of

Tropical Plants”

Instructor: Professor P. Barry Tomlinson,

Professor of Biology Emeritus, Harvard

University &Crum Professor of Tropical

Botany, National Tropical Botanical Garden.

“Biodiversity” is commonly interpreted as a

catalogue of species richness in a given

environment and how it might be preserved,

but it can mean much more if an investigation

considers not just the systematics, of the

organisms in a given area, but their biology,

i.e., structural features in relation to

developmental and functional processes.

Clearly biodiversity in this broad context can be

studied best in the tropics, where diversity is

richest.

South Florida offers a sampling of this richness,

conveniently located in the continental United

States. And the course offers an opportunity at

many levels to become more familiar with

tropical plants and their biological

mechanisms.

The course is intensive and intended to present

an overview of the rich plant diversity in natural

environments (e.g. The Everglades National

Park, Biscayne Bay National Park) and

especially the rich collections of introduced

tropical plants at collaborating Institutions,

notably Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden and

Montgomery Botanical Center, Coral Gables.

Here we have an estimated 10,000 species

representing most major biological groups of

plants. For example, there are well over 500

species of palms (tropical icons) available,

and over 100 plant families not represented in

natural environments in the United States.

Emphasis is on morphology and anatomy in a

systematic and functional context and involves

both field and laboratory study. The course

structure is extensively enquiry-based and is

intended to develop skills in investigative

techniques and philosophical approaches

which can be applied subsequently in Graduate

Study. Students are introduced to many tropical

plant families (especially the iconic Arecaceae)

and such topics as, e.g., tree architecture,

pollination biology, the morphology of vines

and epiphytes as well as distinctive tropical

ecosystems like seagrass meadows and

mangroves. Laboratory work emphasizes

anatomy and dissection of fresh material, using

implements ranging from chain saws to

scalpels, leading to microscopic study in a

well-equipped laboratory.

There are no prerequisites but admission to

the course depends on some demonstrated

previous familiarity with at least elementary

Botany and is intended to cater for students

who are already enrolled in a graduate program

in Botany or Biology or (as undergraduates)

plan to do so in the future.

Students will be required to register with The

Harvard Summer School and will receive 4

credits.

Estimated Cost: Harvard Summer School Tuition

($2,580); travel to and from Miami; Kampong

accommodation at $25 per day; self catering.

Tuition and Travel scholarships may be available for

qualified students.

Dead-line for application: April 15 2011. Early

application is recommended

For further information:-

P.B. Tomlinson at the above Miami address, or,

Harvard Forest, Harvard University, 324 N.Main

St. Petersham MA 01366

e-mail:

pbtomlin@fas.harvard.edu

And Harvard Summer School on-line in 2011

Courses/Workshops

166

Plant Science Bulletin 56(4) 2010

Armen Takhtajan – In

Appreciation of His Life

Peter H. Raven and Tatyana Shulkina,

Missouri Botanical Garden, P.O. Box

299, St. Louis, MO 63166, USA

Takhtajan was a giant both in the field of botany

and as a human being; he will long be

remembered as one of the most illustrious

and effective botanists who ever lived. Over the

course of his long career of scholarship, he

was known and revered throughout the world

for his scholarly contributions as well as for his

unceasing desire to bring together people and

ideas from everywhere, so that we collectively

could produce the very best results of which we

were capable. He not only saw these

relationships clearly but also gave us a personal

model of the way that scholarship and the

community of scientists, working together,

transcends national boundaries and rivalries

and unites us in caring for the world on which

we all depend for our existence.

As a scholar, Takhtajan made critically

important contributions to our understanding

of the evolutionary relationships of vascular

plants and to our understanding of their origins

differentiation, and paths of migration and

dispersal around the world. He based his

conclusions not only on the characteristics of

the plants he knew so well, but also on an

encyclopedic knowledge of the literature of

botany and biology and on the connections that

he nurtured with botanists all over the world.

He was a philosopher who approached the

field of biology in a thoughtful and traditional

way, offering us deep and original insights into

many areas of science.

Tahktajan was of course Armenian to his core,

born June 10, 1910, at Shusha in Nagorny

Karabakh, in the Caucasus; he loved the

people and plants of the whole Caucasus

region and especially of Armenia. He came

from a well educated family. His grandfather

was a journalist, his father, Leon Meliksanovich

Takhtajan, was a specialist in agriculture,

educated in Leipzig, and trained as an

agriculturist in Switzerland, France, and Great

Britain. He knew various European languages

and spoke also Russian, Georgian, and

Armenian at home. Armen’s mother was

descended from the nobel Lasarev’ family that

played an important role in the education of the

Armenian people. Armen himself attended

elementary and high schools in Tbilisi, capital

of Georgia; the city was a cultural center of the

Caucasus that time. After school graduation he

came as a volunteer to Leningrad State

University where he spent there one year,

returning to the Caucasus to complete his

studies. Takhtajan graduated from the Institute

of Subtropical Economic plants (Georgia) in

1932 (that institute no longer exists). During

his academic years his teachers were: V.L.

Komarov (in Leningrad), D.N. Sosnovsky

(Tbilisi), and A.K. Makashvili (Tbilisi). When he

started working he met N.I Vavilov and N.I.

Troitzky. All of these outstanding botanists are

famous in Russia and they contributed much

to the advance of the field. Starting in1935,

Takhtajan was employed as a senior

researcher at the Yerevan Biological Institute;

in 1943 – 1948 he served as director of the

Institute of Botany, Armenian Academy of

Received: 9/8/2010; Accepted 9/15/2010.

Reports and Reviews

167

Plant Science Bulletin 56(4) 2010

Sciences. In his teaching and research at

Yerevan State University, he followed the genetic

results of Morgan and Mendel, politically banned

from the Soviet Union at that time. Consequently,

he was discharged from his academic position

in 1948 – it was Lysenko time. He was 38 years

old. By then, however, Takhtajan was already

well known and appreciated in Russia, and his

Russian colleagues helped him obtain a new

position at Leningrad State University.

On returning to Leningrad in 1949, he became

a professor of the Leningrad State University;

in five years he became the head of the

Paleobotany Laboratory at the Komarov

Botanical Institute, where he was Director

(1976-1986) and adviser until his death (11.13.

2009). All this time he developed his ideas

strongly from a world perspective, and

eventually became a great Russian botanist

whose works and personality were known

throughout the world. Takhtajan formed strong

linkages everywhere he traveled and beyond,

kept his foreign colleagues aware of the

important Russian literature, and brought home

ideas from all countries. For his colleagues in

St. Petersburg, he was indeed a fellow Russian.

Armen Takhtajan’s life spanned a difficult period

of Russian history, and his life was not easy.

He used to joke that his life spanned the period

from Rasputin to Putin, and he lived through

Revolution, repression, World War II, Lysenko,

and the Cold War.

He could survive all these tumultuous and

difficult periods not only because he had a

strong will, but especially also because he had

a wonderful wife. Alice Takhtajan (Davtjan)

was his best friend: they lived together for 57

years. She was a very intelligent, delicate

woman, who left her career in mathematical

linguistics in order to help her husband. She

devoted her life to him and to their three children.

Through all of the troubled periods that he

endured, Takhtajan never sacrificed his

scientific integrity. From 1954 onward, for

some 55 years, he was associated with the

Komarov Botanical Institute, where Director

Pavel Baranov, a courageous and principled

man, hired him and a number of others who

had lost their positions and fallen into disfavor

because of Lysenko’s influence. At the Institute,

Takhtajan continued making great

contributions to the science of botany and to the

development of the work of the staff. He found

this Institute’s large and very rich herbarium,

library and unique living plant collections

essential to the full development of his

thoughts, an incomparable resource on a

global scale.

Over the years, he devoted himself to developing

the classification of angiosperms, a field that

had been somewhat neglected and

undervalued for decades. Takhtajan found

inspiration from his collaboration with

colleagues working in many divisions in the

Komarov Institute, including those concerned

with fields such as paleobotany,

biosystematics, palynology, and morphology

and anatomy. In turn, he was able to suggest

interesting problems with a bearing on

understanding the relationships of different

groups, bringing all of the new knowledge to

bear on his major synthesis. Thus his

interactions with his colleagues enriched his

scientific efforts and those of the colleagues as

well. The research of many Russian scientists

benefited greatly from his advices.

Takhtajan’s ideas about the relationships of

vascular plants were first presented in his work

“Correlations of ontogenesis and phylogenesis

in higher plants,” published in 1943. The

degree of synthesis amounted to a novel

approach to the problem, one that proved fruitful

over the decades to come. He admired the

works of the brilliant synthesizer Kozo-

Polyansky, who in 1924 had written a very

important work on symbiotic relationships

among organisms. These ideas clearly helped

Armen Takhtajan to think more deeply and

imaginatively about phylogeny and philosophy.

We are glad that a translation into English of

Kozo-Polyansky’s thoughtful book, important

in the history of biology, has been published.

Takhtajan’s successive contributions to plant

phylogeny continued with his publication in

1954 and 1959 with Die Evolution der

Angiospermen, in 1967 A System and

Phylogeny of the Flowering Plants, in 1987

System Magnoliophytorum, in 1997 The

Diversity and Classification of Flowering Plants,

and in 2009 Flowering Plants. Throughout the

60 years that he studied plant phylogeny, he

exhibited his skills and extraordinary memory

168

Plant Science Bulletin 56(4) 2010

as a synthesizer, bringing new findings from

many fields to bear on his conclusions and

presenting fresh hypotheses for further

consideration in each of his works. By the end

of his career he regularly took molecular data

into account in modifying his early ideas. He

also readily learned about the power of

computers and data bases, using them to

provide further information for his studies and

to form his ever-evolving conclusions.

Deeply knowledgeable about plant structure,

Takhtajan formulated a number of

macroevolutionary hypotheses, such as those

concerning heterobatmy and heterochrony,

which have inspired thoughtful discussion by

scholars such as Agnes Arber and Steven

Gould. He concluded that herbaceous plants

had originated as a result of neoteny, an idea

that has been partly accepted by others. He

produced a novel classification of gynoecia

and their placentation, and critically evaluated

such areas as the structure of inflorescences

and the evolution of pollen grains. He analyzed

the origins of monocot leaves, with their

characteristic parallel venation, and attempted

to explain the processes by which they were

formed. Because of his wide knowledge of

both Russian and world literature as well as

his outstanding personality, Takhtajan was

able to bring scholars everywhere into contact,

foster their cooperative efforts, and inform their

studies with new knowledge.

Peter Raven first met Armen Takhtajan in 1971,

when he was a member of the faculty at Stanford

University, and, like others who knew him, was

immediately deeply impressed with his

humanity, friendly personality, and the depth of

his scholarship. At his invitation, Raven

participated in the International Botanical

Congress here in 1975, developing a

symposium on the symbiotic original of

organelles such as mitochondria and

chloroplasts, and thus fostering the ideas of

Kozo-Polyansky that Armen had appreciated

so deeply. During the last 30 years of his life,

he enjoyed visiting and studying at The New

York Botanical Garden and the Missouri

Botanical Garden, where colleagues were

inspired by him and came to love him and his

wife Alice. We are delighted that we will be able

to produce an English version of the second

edition of his book, “Towards Universal

Science,” a book that will bring his general and

philosophical views about the philosophy of

science. Charles Jeffrey has done a good

service in translating this book and thus making

Takhtajan’s views available to a wider audience

than it had been previously. In the book,

Takhtajan seeks to formulate the general laws

governing the organization, structure, and

transformation of systems common to all

sciences and operative at all structural levels.

He hoped that tectology would become the

basis of a new world view of science as a whole

and a powerful force for the integration of

scientific knowledge and its utilization for

mankind.

What will be the future trends in areas of interest

to Armen Takhtajan, and how did his studies

contribute to the ways in which they will develop?

First, of course, is his significant contribution to

the internationalization of science, which has

helped us all realize that ideas and scientific

progress know no boundaries. We are together

engaged in an endless search for knowledge

that humans have known from the time of their

origins and will go on as long as our species

exists on earth. In science, we find a common

language that enables us to communicate with

and understand one another in ways and for

purposes that are deeply important for us all.