69

Table of Contents

Society News

Merit Award: Dr. Michael Donoghue; Dr. Jeff Doyle; Dr. James Doyle ..........................70

Charles E. Bessey Award: Dr. Bruce Kirchoff .................................................................72

Young Investigator Award: Dr. Stacey Smith ...................................................................72

The second annual BSA Public Policy Award, BESC Congressional Visits Day 2014 ...77

American Journal of Botany continues Centennial Celebration throughout 2014 ...........81

Whitney R. Reyes Student Travel Award provides funds for to attend Botany 2014 .....87

BSA Science Education News and Notes ......................................................

88

Announcements

Meet the new Editors ........................................................................................................91

Up close with Theresa Culley ...........................................................................................92

Triarch “Botanical Images” Student Travel Awards .........................................................96

Missouri Botanical Garden Herbarium ...........................................................................98

Editor’s Choice ..............................................................................................

99

Reports

Geocaching as a means to teach botany to the public. ...................................................100

Book Reviews

Ecological .......................................................................................................................104

Economic Botany ...........................................................................................................105

Systematics ....................................................................................................................108

Books Received ...........................................................................................

111

Botany 2014 Invited Speakers ......................................................................

112

July 26 - 30 2014 - The Boise Centre - Boise, Idaho

www.botanyconference.org

70

Society News

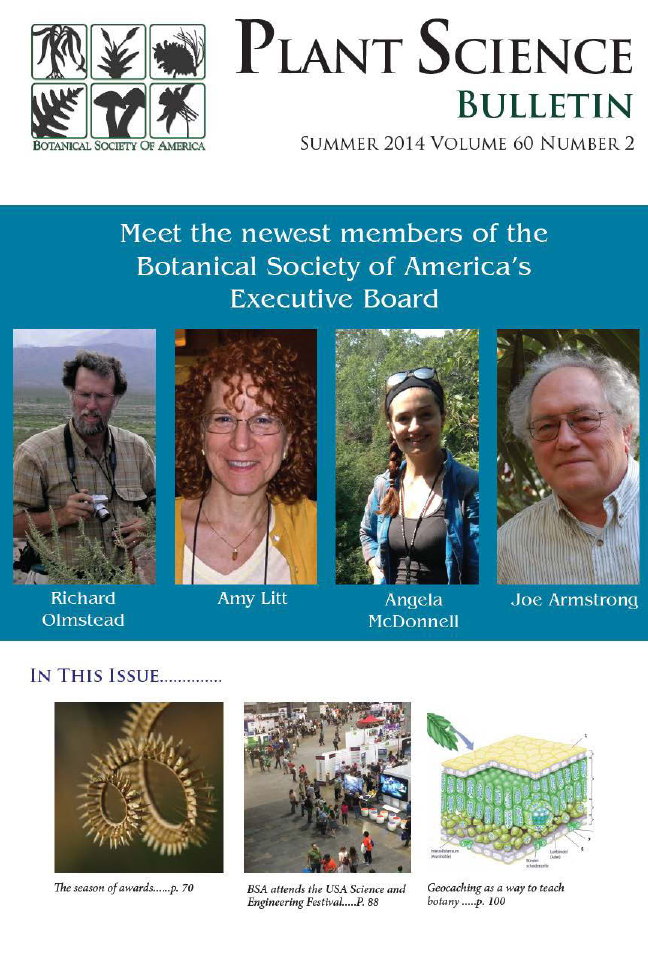

The Botanical Society of America’s

2014 Merit Award Winners

Congratulations!

The Botanical Society of America Merit Award is the highest honor our Society bestows. Each year, the

Merit Award Committee solicits nominations, evaluates candidates, and selects those to receive an award.

Awardees are chosen based on their outstanding contributions to the mission of our scientific Society. The

committee identifies recipients who have demonstrated excellence in basic research, education, and public

policy, or who have provided exceptional service to the professional botanical community, or who may

have made contributions to a combination of these categories. Based on these stringent criteria, the 2014

BSA Merit Award recipients are listed in the following pages.

Dr. James Doyle

University of

California - Davis

Professor James A. (Jim) Doyle is recognized for

his many distinguished contributions to paleobotany,

particularly palynology, and to the understanding

of angiosperm phylogeny. Doyle and his associates

demonstrated that, worldwide, the Cretaceous fossil

record shows the primary adaptive radiation events of

early angiosperm evolution. One of his most valuable

insights, derived from both cladistic analysis and

stratigraphy, was the observation that angiosperms with

tricolpate and tricolpate-derived pollen corresponded to

a clade of angiosperms that included the vast majority of

living flowering plants. The existence of such a clade, the

eudicots, has subsequently been strongly supported by

molecular analyses, and the concept has made its way into

modern botany and biology textbooks. Throughout his

career and continuing into retirement, Prof. Doyle has shown himself to be an outstanding and inspiring

teacher, at both the undergraduate and graduate level. His lectures are meticulously organized, expertly

delivered, and focused on principles yet packed with details. His quirky sense of humor emerges and

students are left amazed by how much they learned. Prof. Doyle trained nine graduate students over his

career and mentored innumerable other graduate students, postdocs, and faculty colleagues.

71

Plant Science Bulletin 60(2) 2014

Dr. Michael Donoghue is a world-renowned botanist

and a tireless champion of phylogenetics, evolution,

and biodiversity research. He is an elected Fellow of the

National Academy of Sciences (2005) and the American

Academy of Arts and Sciences (2008), and most recently

was awarded the prestigious Dahlgren Prize in Botany

from the Royal Physiographic Society of Sweden

(2011). Donoghue has consistently been ahead of his

time—an intellectual leader in the development of new

theory and approaches in systematics, species concepts,

character evolution, historical biogeography, lineage

diversification, and phylogenetic nomenclature. His ideas

are always provocative; he has consistently rocked the

boat, inspired debate, and moved all of us toward more

rigorous thought.

His prodigious research career (he has published

hundreds of papers) is matched by his inspired, continual

service to our community, including many years in the

Directorships of the Harvard University Herbaria and the Yale Peabody Museum. He has also trained and

mentored dozens of students and post-doctoral associates, many of whom are now leaders themselves.

All of his nomination letters make special note of how naturally Michael inspires his colleagues—and the

botanical community at large—with his ideas and creativity, his enthusiasm, and his enormous generosity.

Dr. Michael Donoghue

Yale University

Dr. Jeffrey Doyle

Cornell University

Dr. Jeffrey Doyle is an internationally recognized leader

in the fields of theoretical and phylogenetic plant molecular

systematics and molecular evolution. Over the past several

decades he has consistently been at the forefront of the

field of molecular plant systematics, contributing not only

innovative methods, but also conceptual advances, as well

as new empirical findings that have led to an improved

understanding of plant diversity. One letter-writer notes

that Dr. Doyle has “an astonishing…record of insightful and

sustained scientific achievement and has an immense impact

on the direction of our field.” Dr. Doyle has made major

contributions to clarifying evolutionary relationships among

the legumes, the evolution of nodulation and also on the significance of polyploidy. Importantly, one letter-

writer notes that Dr. Doyle’s “commitment to undergraduate education is every bit as impressive as his

research and scholarship.” Dr. Doyle was not only an effective undergraduate teacher but also held a major

administrative position at Cornell, Director of the Office of Undergraduate Biology,

72

Plant Science Bulletin 60(2) 2014

BRUCE K. KIRCHOFF RECEIVES THE 2014

CHARLES E. BESSEY AWARD

The 2014 recipient of the Bessey Award is Professor Bruce K. Kirchoff

(University of North Carolina, Greensboro). Dr. Kirchoff has been on the

faculty at Greensboro since 1986 where he has distinguished himself as a

plant morphologist and botanical educator. He is a former member of the

BSA Education Committee and served as chair in 1993-94. His botanical

education research on image recognition is a direct outgrowth of his

morphological studies.

Dr. Kirchoff is transforming the way that students learn through the

creation of active, visual learning programs and mobile applications. He

has created, validated, and is in the process of distributing groundbreaking

software that helps students more easily master complex subjects. Furthermore, he has collaborated not

only with scientists in the U.S., but also Europe and Australia, to adapt his visual learning software to local

problems such as helping Australian veterinary students recognize poisonous plants and providing visual

identification keys for tropical African woods.

In 2007 he was the BSA Education Booth Competition winner for Image Quiz: A new approach to

teaching plant identification through visual learning and his work was showcased in the Education Booth

at the Botany & Plant Biology 2007 Joint Congress in Chicago. In 2013 he was the inaugural recipient of

the American Society of Plant Taxonomists (ASPT) Innovations in Plant Systematics Education Prize and

this year he was recognized with the University of North Carolina System Board of Governors award for

Excellence in Teaching.

Stacey Smith Receives Inaugural BSA

Emerging Leader Award

Dr. Stacey Smith is an accomplished researcher with a true commitment

to education and outreach and a willingness to step into leadership roles. She

is currently an assistant professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

Smith did her undergraduate work at Virginia Tech, earned a Master’s on

a Marshall Fellowship at the Universities of Reading and Birmingham, and

then obtained a PhD in Botany from the University of Wisconsin in 2008.

After doing a post-doc at Duke University, and spending 3 years on the

faculty at the University of Nebraska, she took her current position in 2013.

Over that time Dr. Smith has proven herself to be a prolific researcher,

with more than 25 publications, including co-authorship of the book, Tree

Thinking: An Introduction to Phylogenetic Biology.

Dr. Smith is best known for her work on Iochrominae (Solanaceae),

a clade that she has turned into a spectacular model system for bridging

ecological studies of pollination biology with genetic studies of the biochemical and genetic basis of

floral diversity. In addition, she has collaborated on diverse evolutionary studies and has made important

contributions in phylogenetic theory. However, as noted by her nominator, “Stacey is not just a great

researcher, but also a committed educator.” She has been active in traditional university courses, diverse

outreach activities especially in a K-12 setting, and as a resource instructor for the OTS Tropical Plant

Systematics course. She has also played an important role in identifying the challenge of teaching tree

thinking and in providing resources to help teachers overcome those challenges. Finally, it has been noted

that Dr. Smith is “a generous and supportive person who leads by example and draws along many other

junior (and senior) colleagues in her wake.” Given all these contributions to botany, Dr. Smith is a very

fitting recipient of the inaugural BSA Emerging Leader Award.

73

Plant Science Bulletin 60(2) 2014

BSA Public Policy Award

The Public Policy Award was established

in 2012 to support the development of

tomorrow’s leaders and a better understanding

of this critical area. The 2014 recipients are:

Megan Philpott, University of Cincinnati and the

Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden, and Steven

Callen, Saint Louis University.

The BSA Graduate Student

Research Award

including the J. S. Karling

Award

The BSA Graduate Student Research Awards

support graduate student research and are made

on the basis of research proposals and letters of

recommendations. Within the award group is the

J. S. Karling Graduate Student Research Award.

This award was instituted by the Society in 1997

with funds derived through a generous gift from

the estate of the eminent mycologist, John Sidney

Karling (1897-1994), and supports and promotes

graduate student research in the botanical sciences.

J. S. Karling Graduate

Student Research Award

Catherine Rushworth, Duke University -

Advisor, Dr. Thomas Mitchell-Olds, Insights into the

origin and persistence of apomixis in the Boechera

holboellii species complex

BSA Graduate Student

Research Awards

Jason Berg, University of Maryland - Advisor,

Dr. Elizabeth Zimmer, A molecular assessment

of the potentially invasive plant species, Mimulus

guttatus DC: Estimating genetic divergence,

migration rates, and selfing rates for naturalized and

invasive populations in North America and Europe

Andrew A. Crowl, University of Florida and the

Florida Museum of Natural History - Advisor, Dr.

Nico Cellinese, Integrating morphology, cytology,

niche modeling, and phylogenetics to understand the

evolutionary history of endemic Campanula Species

in the Mediterranean

Jessamine Finch, Northwestern University

and Chicago Botanic Garden - Advisor, Dr. Kayri

Havens-Young, The effects of climate change on plant

regeneration: linking neighborhood size, tolerance

range, and species responses

Elliot Gardner, Northwestern University

and Chicago Botanic Garden - Advisor,

Dr. Nyree Zerega, Pollination biology of

domesticated artocarpus J.R. Forst. & G. Forst.

(Moraceae)

Alannie-Grace Grant, University of Pittsburgh -

Advisor, Dr. Susan Kalisz, Testing the preemptive selfing

hypothesis—Does self-pollination limit hybridization

in co-flowering related species?

Kimberly Hansen, Northern Arizona University -

Advisor, Dr. Tina J Ayers, Reconstructing the evolutionary

history of Campanulaceae with NextGen sequencing

Carla J. Harper, University of Kansas - Advisor,

Dr. Thomas N. Taylor, Fungal diversity during the

Permian and Triassic of Antarctica

Karolina Heyduk, University of Georgia -

Advisor, Dr. Jim Leebens-Mack, Physiology and

evolutionary genomics of CAM photosynthesis

in Yucca (Asparagaceae)

Brian Hoven, Miami University - Advisor, Dr.

David L. Gorchov, The effect of emerald ash borer-

caused canopy gaps on understory invasive shrubs

and forest regeneration

Kelly Ksiazek, Northwestern University and

Chicago Botanic Garden - Advisor, Dr. Krissa

Skogen, Pollen movement on urban green roofs

Emily Lewis, Northwestern University and

Chicago Botanic Garden - Advisor, Dr. Krissa

Skogen, Using pollinator foraging distance to

predict genetic differentiation in hawkmoth and bee-

pollinated Oenothera species

Shih-Hui Liu, Saint Louis University and the

Missouri Botanical Garden - Advisor, Dr. Jan

Barber, Phylogeny of Ludwigia and polyploid

evolution in section Macrocarpon (Onagraceae)

Blaine Marchant, University of Florida and the

Florida Museum of Natural History - Advisors,

Drs. Douglas and Pamela Soltis, Investigations into

the fern genome: filling the missing link in land plant

genome evolution

Renee Petipas, Cornell University - Advisor, Dr.

Monica Geber, The contribution of root-associated

microbes to plant local adaptation

Clayton Visger, University of Florida and the

Florida Museum of Natural History - Advisors, Drs.

Douglas and Pamela Soltis, Genomic consequences

of autopolyploidy: Gene expression in diploid and

autopolyploid Tolmiea (Saxifragaceae)

74

Plant Science Bulletin 60(2) 2014

Emily Warschefsky, Florida International

University and the Fairchild Tropical Botanic

Garden - Advisor, Dr. Eric J. B. von Wettberg, Next-

generation domestication genetics of the mango (m.

indica l.)

Keir Wefferling, University of Wisconsin -

Milwaukee - Advisor, Dr. Sara Hoot, Speciation

and hybridization in Caltha leptosepala s.l.

(Ranunculaceae): Disentangling the subalpine

marsh-marigold species complex

Kevin Weitemier, Oregon State University - Advisor,

Dr. Aaron Liston, Genome-enabled phylogeography

of a Great Basin milkweed, Asclepias cryptoceras

Brett Younginger, Portland State University -

Advisor, Dr. Daniel Ballhorn, The diversity and

functional role of foliar endophytes in stress-tolerant

plants

Vernon I. Cheadle Student

Travel Awards

(BSA in association with the

Developmental and Structural

Section)

This award was named in honor of the memory

and work of Dr. Vernon I. Cheadle.

Carla Harper, University of Kansas - Advisor,

Dr. Thomas N. Taylor - for the Botany 2014

presentation: “Foliar fossil fungi: Leaf–fungal

interactions from the Permian and Triassic of

Antarctica” Co-authors: Thomas N. Taylor, Michael

Krings and Edith L. Taylor

Rebecca Koll, University of Florida, Florida

Museum of Natural History - Advisor, Dr. Steven

Manchester - for the Botany 2014 presentation:

“Taxonomic relationships of early and middle

Permian gigantopterid seed plants in western

Pangea” Co-author: Steven Manchester

Meghan McKeown, University of Vermont

- Advisor, Dr. Jill Preston - for the Botany 2014

presentation: “The Evolution of vernalization

responsiveness in temperate Pooideae” Co-author:

Jill Preston

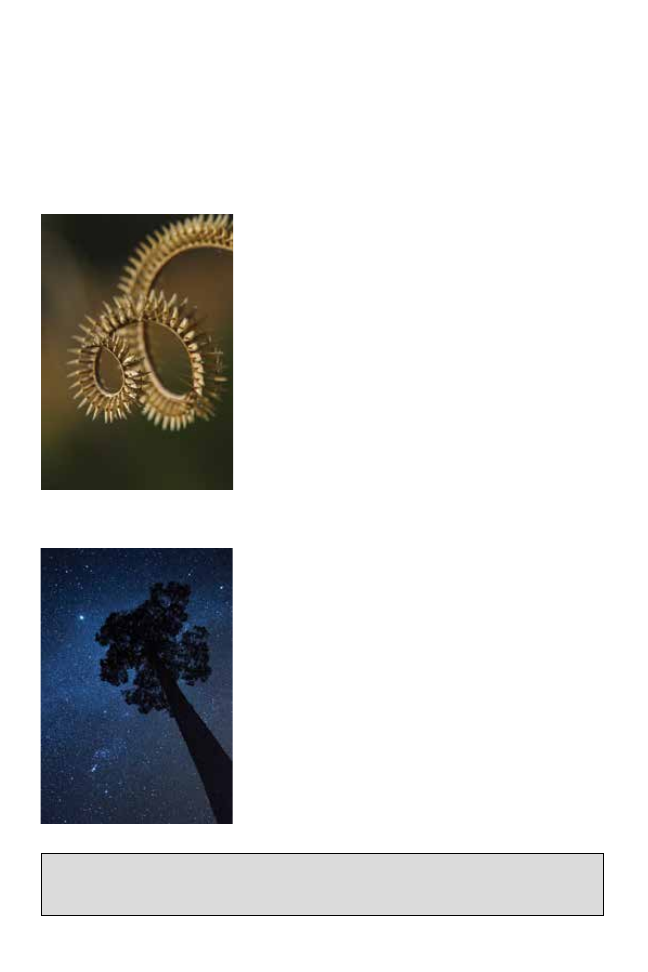

Triarch “Botanical Images”

Student Travel Awards

This award provides acknowledgement and travel

support to BSA meetings for outstanding student

work coupling digital images (botanical) with

scientific explanations/descriptions designed for

the general public. See the July American Journal of

Botany for all submissions.

Daniel McNair, University of Southern

Mississippi - 1st Place, Graceful aging, $500 Botany

2014 Student Travel Award

Daniel McNair, University of Southern

Mississippi - 2nd Place, Last of the longleaf

Abby Glauser, University of Kansas -

3rd Place, Resilience, $250 Botany 2014 Student

Travel Award

Carla Harper, University of Kansas -

3rd Place, 260 million year old (Permian)

mycorrhizal fungi from Antarctica, $250 Botany

2014 Student Travel Award

The BSA Undergraduate

Student Research Awards

The BSA Undergraduate Student Research

Awards support undergraduate student research

and are made on the basis of research proposals

and letters of recommendation. The 2014 award

recipients are:

Meredith R. Breeden, Fort Lewis College -

Advisor, Dr. Ross A. McCauley, Pollination biology

of the narrow endemic Ipomopsis ramosa, in

Roaring Fork Canyon, CO

Alice Butler, Bucknell University - Advisor,

Dr. Chris Martine, Floral development in solanum

sejunctum and solanum asymmetriphyllum

Matthew Galliart, Kansas State University

- Advisor, Dr. Loretta Johnson, Long-term field

selection of big bluestem ecotypes in reciprocal

gardens planted across the Great Plains precipitation

gradient

Ian Gilman, Bucknell University - Advisor, Dr.

Chris Martine, Field botany and population genetics

of Draba L. (Brassicaceae) in the Rocky Mountains

Morgan Roche, Bucknell University - Advisor,

Dr. Chris Martine, Genetic diversity within and

among species of dioecious Australian solanum

75

Plant Science Bulletin 60(2) 2014

Dylan D. Sedmak, Ohio State University -

Advisor, Dr. John Freudenstein, Fungal variability

and habitat correspondence in the North American

orchid Cypripedium acaule ait.

Kayla Ventura, University of Florida - Advisor,

Dr. Pamela Soltis, Identifying the cellular component

of flower size differences in Gilia (Polemoniaceae)

associated with changes in pollinators

Developmental & Structural

Section Student Travel Awards

Italo Antonio Cotta Coutinho, Universidade

Federal de Vicosa - Advisor, Renata Maria Strozi

Alves Meira - for the Botany 2014 presentation:

“Diversity of secretory structures in Urena

lobata L.: ontogenesis, anatomy and biology of the

secretion” Co-authors: Sara Akemi Ponce Otuki,

Valéria Ferreira Fernandes, Renata Maria Strozi

Alves Meira

Roux Florian, INRA - Advisor, Jana Dlouhá - for

the Botany 2014 presentation: “Flexible juveniles or

why trees produce ‘low quality’ wood?” Co-authors:

Jana Dlouhá, Tancrède Almeras, Meriem Fournier

Rebecca Povilus, Harvard University -

Advisor, William Friedman - for the Botany

2014 presentation: “Pre-fertilization reproductive

development and floral biology in the remarkable

water lily, nymphaea thermarum” Co-authors: Juan

M. Losada, William E. Friedman

Beck Powers, University of Vermont - Advisor,

Jill Preston - for the Botany 2014 presentation:

“Evolution of asterid HANABA TARANU-like genes

and their role in petal fusion” Co-author: Jill Preston

Ecology Section Student

Travel Awards

Rachel Germain, University Of Toronto -

Advisor, Dr. Benjamin Gilbert - for the Botany 2014

presentation: “Hidden responses to environmental

variation: maternal effects reveal species niche

dimensions” Co-author: Benjamin Gilbert

Jessica Peebles Spencer, Miami University -

Advisor, Dr. David L. Gorchov - for the Botany

2014 presentation: “Effects of the Invasive Shrub,

Lonicera maackii, and a Generalist Herbivore,

White-tailed Deer, on Forest Floor Plant Community

Composition” Co-author: David L. Gorchov

Genetics Section Student

Research Awards

Genetics Section Student Research Awards

provide $500 for research funding and an additional

$500 for attendance at a future BSA meeting.

Kevin Weitemier, Oregon State University-

Graduate Student Award - Advisors: Dr. Aaron

Liston, for the proposal titled “Genome-enabled

phylogeography of a Great Basin milkweed, Asclepias

cryptoceras”

Kimberly Hansen,

Northern Arizona

University- Masters Student Award - Advisor: Dr.

Tina Ayers, for the proposal titled “Reconstructing

the evolutionary history of Campanulaceae with

NextGen sequencing”

Pteridological Section &

American Fern Society Student

Travel Awards

Alyssa Cochran, University of North Carolina,

Wilmington - Advisor, Dr. Eric Schuettpelz - for

the Botany 2014 presentation: “Tryonia, a new

taenitidoid fern genus segregated from Jamesonia

and Eriosorus (Pteridaceae)” Co-authors: Jefferson

Prado and Eric Schuettpelz

Jordan Metzgar , University of Alaska, Fairbanks

- Advisor, Dr. Stefanie Ickert-Bond - for the Botany

2014 presentation: “From eastern Asia to North

America: historical biogeography of the parsley ferns

(Cryptogramma)” Co-author: Stefanie Ickert-Bond

Jerald Pinson, University of North Carolina,

Wilmington - Advisor, Dr. Eric Schuettpelz - for

the Botany 2014 presentation: “Origin of Vittaria

appalachiana, the “Appalachian gametophyte”” Co-

author: Eric Schuettpelz

Sally Stevens, Purdue University - Advisor, Dr.

Nancy C. Emery - for the Botany 2014 presentation:

“Home is Where the Heat Is? Temperature and

Humidity Responses in a Fern Gametophytex” Co-

author: Nancy C. Emery

76

Plant Science Bulletin 60(2) 2014

The BSA Young Botanist

Awards

The purpose of these awards is to offer individual

recognition to outstanding graduating seniors

in the plant sciences and to encourage their

participation in the Botanical Society of America.

The 2014 “Certificate of Special Achievement”

award recipients are:

Theresa Barosh, Willamette University, Advisor:

Dr. Susan Kephart

Allison Bronson, Humboldt State University,

Advisor: Dr. Alexandru M. Tomescu

Jamie Burnett, Humboldt State University,

Advisor: Dr. Alexandru M. Tomescu

Katherine Chapel, Miami University, Advisor:

Dr. Michael A. Vincent

Nels Christensen, Connecticut College, Advisor:

Dr. T. Page Owen, Jr.

Gemma Dugan, Bucknell University, Advisor:

Dr. Chris Martine

Vince Fasanello, Bucknell University, Advisor:

Dr. Chris Martine

Leila Fletcher, Barnard College, Columbia

University, Advisor: Dr. Hilary Callahan

Anna Freundlich, Bucknell University, Advisor:

Dr. Chris Martine

Maria Friedman, Humboldt State University,

Advisor: Dr. Alexandru M. Tomescu

Blake Geraci, University of Florida, Advisor: Dr.

Pamela S. Soltis

Grace Glynn, Connecticut College, Advisor: Dr.

T. Page Owen, Jr.

Cody Groen, College of St. Benedict/St. John’s

University, Advisor: Dr. Stephen G. Saupe, Ph.D.

Anna Herzberger, Eastern Illinois University,

Advisor: Dr. Scott J. Meiners, Ph.D

Julia Hull, Weber State University, Advisor: Dr.

Ron Deckert, Ph.D.

Emily Keil, Ohio University, Advisor: Dr. Sarah

E. Wyatt

Michael LeDuc, Connecticut College, Advisor:

Dr. T. Page Owen, Jr.

Jessica Mikenas, Oberlin College, Advisor: Dr.

Michael J. Moore

Luis Mourino, University of Florida, Advisor:

Dr. Pamela S. Soltis

Taylor J. Nelson, Weber State University,

Advisor: Dr. Sue Harley

Chelsea Obrebski, Miami University, Advisor:

Dr. Michael A. Vincent

Rhys Ormond, Willamette University, Advisor:

Dr. Susan Kephart

Kelsey Phipps, Eastern Illinois University,

Advisor: Dr. Scott J. Meiners, Ph.D.

Molly Sutton, Weber State University, Advisor:

Dr. Barb Wachocki

Amanda Thornton, Campbell University,

Advisor: Dr. Chris Havran

Drew Walters, Fort Lewis College, Advisor: Dr.

Ross A. McCauley, Ph.D.

The BSA PLANTS Grant Recipients

The PLANTS (Preparing Leaders and Nurturing

Tomorrow’s Scientists) program recognizes outstanding

undergraduates from diverse backgrounds and provides

travel grants and mentoring for these students.

Marilyn Creer, Alabama A&M University,

Advisor: Dr. Tatiana Kukhtareva

Gemma Dugan, Bucknell University, Advisor:

Dr. Chris Martine

Shawna Faulkner, Humboldt University,

Advisor: Dr. Alexandru Tomescu

Michelle Garcia, University of Texas-El Paso,

Advisor: Dr. Michael Moody

Aidee Guzman, University of Wisconsin-

Madison, Advisor: Dr. Eve Emshwiller

Timothy Hieger, University of Kansas, Advisor:

Dr. Thomas N. Taylor

Shayla Hobbs, University of Illinois, Advisor:

Dr. Tina M. Knox

Michelle Jackson, Smith College, Advisor: Dr.

Jesse Bellemare

Claudia Christine Marin, University of

California Riverside, Advisor: Dr. Milton McGiffen

Sean Pena, Florida International University,

Advisor: Dr. Suzanne Koptur

David Pozo Garces, Central Michigan State

University, Advisor: Dr. Anna Monfils

Yisu Santamarina, Florida International

University, Advisor: Dr. Bradley Bennett

Samuel Torpey, University of Idaho, Advisor:

Dr. David Tank

77

Plant Science Bulletin 60(2) 2014

BSA students participate in

Congressional Visits Day 2014

BSA Public Policy Award offers

unique and personal experience in

Washington, DC

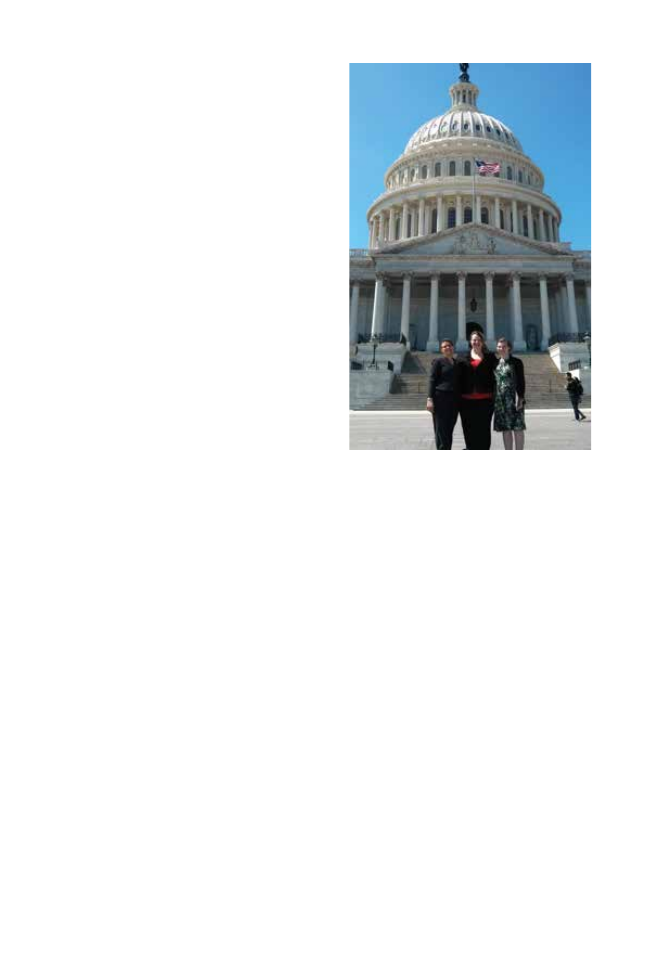

On April 9-10, BSA graduate student members

Megan Philpott (University of Cincinnati), Steven

Callen (Saint Louis University), and Morgan Gostel

(George Mason University) met with members

of Congress to discuss the importance of funding

for basic scientific research through the National

Science Foundation (NSF). This was the third year

that BSA student members have participated in this

annual event, organized by the American Institute

of Biological Sciences (AIBS) and the Biological and

Ecological Science Coalition (BESC) for biologists

to meet with members of congress.

As a bit of background, this year President

Obama’s budget proposal requested $7.255 billion in

appropriations for the National Science Foundation.

This is 1.2% more than last year’s request. Recently,

appropriations request letters were submitted to

House (Representative Butterfield, D–MA) and

Senate (Senator Markey, D–NC) appropriations

committees, requesting this amount be increased

to $7.5 billion for FY 2015, which helps to mitigate

net losses due to inflation and maintains support

for important NSF programs.

Megan and Steven are recipients of the second

annual BSA Public Policy Award and have

described their experience below.

Megan’s experience

Fellow BSA Public Policy Award winner Steven

Callen and I met with BSA student representative,

Morgan Gostel, the day before the festivities

started to get oriented. April 9 kicked off with a

meeting between the first-time Congressional

Visits attendees and members of the scientific

community with extensive experience in public

policy. It was a candid look into the day-to-

day world of communicating science to policy-

makers. Afterward, we got a run-down of the

political climate in Congress right now regarding

science policy and research, the proposed budgets

for various scientific research agencies for 2015,

and how exactly to communicate effectively with

policy-makers regarding our requests.

April 10 was the big day to meet with our

Congress people. I was in a group with two other

graduate students representing Michigan and

Pennsylvania, led by Brian Wee, Chief of Strategic

Alliances for the National Ecological Observatory

Network. We each met with the offices of our two

state senators and state representative, and I led

the meetings with my Ohio congressmen, Sen.

Sherrod Brown, Sen. Rob Portman, and Rep. Steve

Chabot. Our main request was a modest increase

for the NSF budget in FY2015 to $7.5 billion, up

from the proposed budget of $7.255 billion. Most

of the offices we met with seemed very supportive

of funding basic scientific research in their state,

but time and time again, legislative staff stressed

the difficulty of passing any budget increases

given the current political climate. According to

the AIBS, several of the Senator’s offices that CVD

participants met with signed a “Dear Colleague”

letter circulated in support of an increased NSF

budget, so hopefully our meetings had a positive

impact.

All in all, my involvement with CVD was an

eye-opening and educational experience. It’s easy

to get discouraged as a citizen when it feels like

your elected officials don’t share your priorities,

but actually going to Capitol Hill and meeting

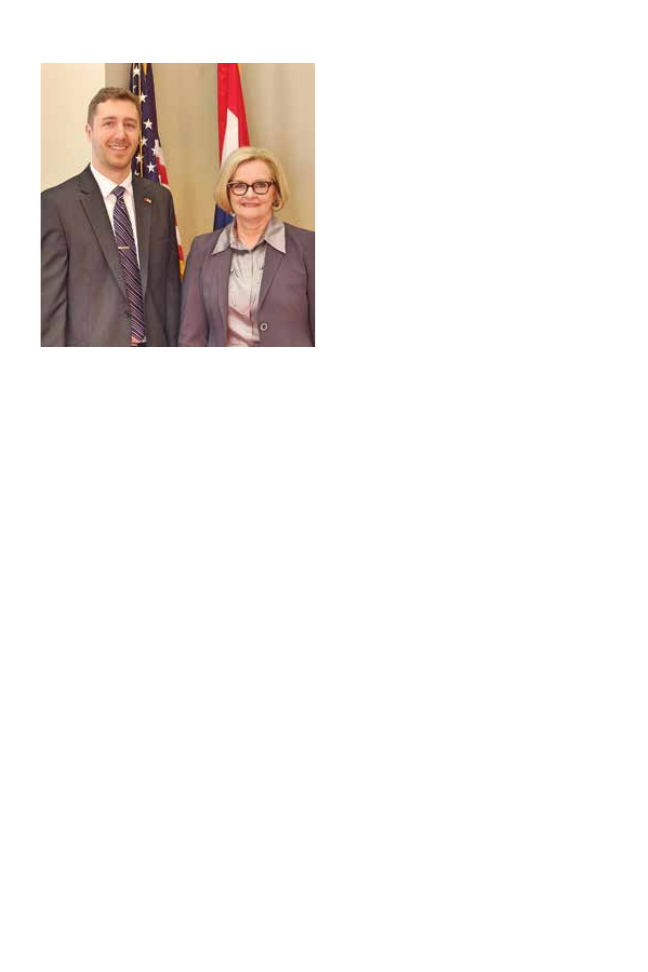

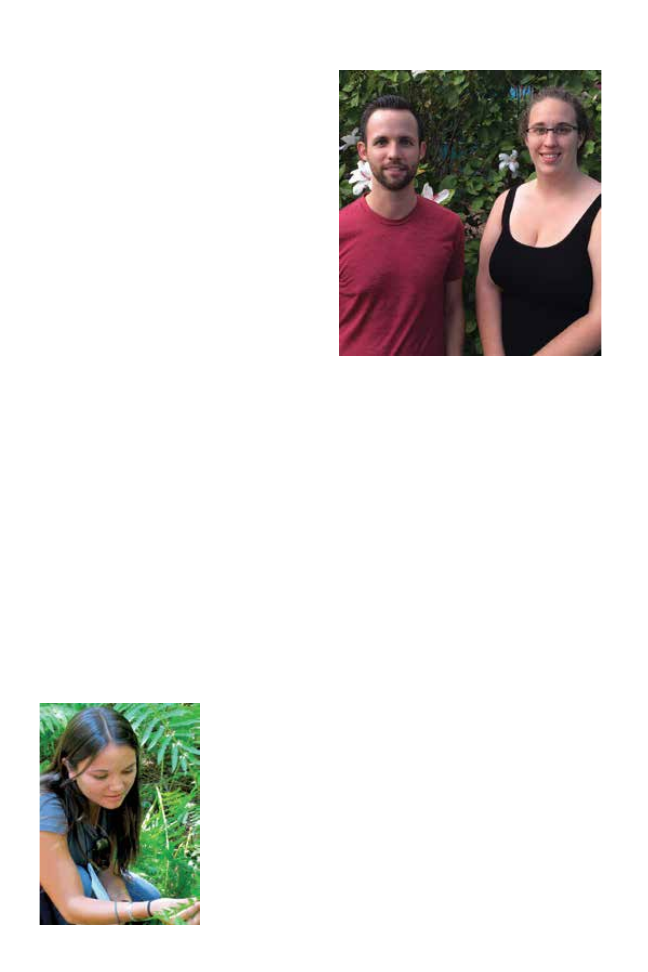

Megan Philpott, University of Cincinnati (right),

with two other graduate students during Congres-

sional Visits Day 2014.

78

Plant Science Bulletin 60(2) 2014

with congressional offices showed that we citizens

can have a little more impact than just going to

the polls on Election Day. I feel inspired to stay

involved with science advocacy and public policy

at the federal level, and I’m currently trying to

get involved at the state level as well. In all, I’m

incredibly grateful to the BSA for allowing me to

have such a great experience.

Steven’s experience

Until my visit to the U.S. Embassy in Beijing

last summer during my 2013 NSF East Asian

and Pacific Summer Institute Fellowship, I had

never considered, or even thought about, how

important science policy and policymakers are

in directing the landscape of scientific research

and development in the United States and in

supporting my own research. Inspired by that

embassy visit, I subsequently began to increase

my awareness and understanding of issues in

science policy and actively started to find avenues

for student participation in policy that would

consequently give me the chance to have an impact

on the current state and future direction of science

R&D. Thanks to the Botanical Society of America,

I was able to take a significant step in that direction

by immersing myself in part of the science policy

process by attending CVD this year.

Our group was lead by Richelle Weihe,

Governmental Grants and Contracts Coordinator

at the Missouri Botanical Garden, and also

included Chris Lorentz (from Thomas More

College in Kentucky) and Don Natvig (from the

University of New Mexico). Since there were four

of us representing three states, we were tasked

with having conversations with Senate and House

members (or their staff) from Missouri (Sen.

McCaskill, Sen. Blunt, and Rep. Clay), Kentucky

(Sen. Paul, Sen. McConnell, and Rep. Massie), and

New Mexico (Sen. Udall, Sen. Heinrich, and Rep.

Lujan Grishman).

What was particularly unique about this group

of Senators and Representatives was the diversity

of their backgrounds: five are Democrats and four

are Republicans; two are women; one is African-

American; collectively they come from six different

religious backgrounds; and, while most are in their

first term, they have different levels of experience

in Congress (up to seven terms)! As a result, it

was interesting seeing first-hand the different

ways that each of their offices operated, their levels

of understanding how science works, and their

individual perspectives on federal funding for

science R&D.

For instance, while the office of Sen. McCaskill

(D-MO) expressed support for federally supported

science research, though her policy is to generally

not sign letters of support for any issue, Sen. Rand

Paul’s (R-KY) office bluntly suggested that the best

we could hope for, since this is an election year,

is to maintain status quo until some time in the

following year, but that his office is generally in

favor of across-the-board budget cuts (not just to

the sciences). Alternatively, the office of Sen. Wm.

Lacy Clay (D-MO) was uniquely transparent in

their complete support of increased federal funding

to science research, which actually was evident

before our meeting, as he had, just days before,

signed the Butterfield-McKinley Dear Colleague

Letter in support of a $7.5 million budget for

NSF for fiscal year 2015 ($245 million more than

currently proposed by Pres. Obama).

While the entire day was full of excitement and

“teachable moments” for me, my experience at

CVD both began and ended with my two biggest

highlights. As residents of Missouri, Richelle

and I were both able to attend Sen. McCaskill’s

constituent coffee hour (along with vacationers

and groups advocating for different issues). It was

a little intimidating meeting with a member of

Congress for the first time, but I was quickly put

at ease by Sen. McCaskill’s sense of humor and

straightforward demeanor. After listening to her

Steve Callen, Saint Louis University, meets with

Senator Claire McCaskill (D-MO) during Congres-

sional Visits Day 2014

79

Plant Science Bulletin 60(2) 2014

tell us about the current state of things in the Senate

and then having our photo taken with her, we met

with one of her policy analysts in the hallway and

were able to get into more detail about the need for

federal funding for science, how it has been used

to support our own work, and other ways in which

federal funding has benefitted science R&D and

STEM training in Missouri. Our message was well-

received, and, just before we left, I offered myself as

an eager source of advice on future science policy

issues.

Toward the end of the day, our group had a

meeting with Rep. Clay. We were not planning on

meeting with him, but, to our surprise, he was in

his office and quickly stepped out to greet us and

say “hello” before he had to run off to vote. A bit

mystified by his unexpected appearance, I collected

myself and was directed into a room to speak

with one of his legislative assistants, Ms. Noelle

Lindsay. The two of us bonded immediately as a

result of some common ground. After I explained

how federal funding is helping to support my

dissertation project on an invasive plant species,

she told me how her dad struggles to remove the

same plant from his backyard year after year! As

Richelle and I were leaving the office, Ms. Lindsay,

laughing, mentioned she was going to text her dad

that she met someone whose research might help to

relieve some of his backache.

Overall, I greatly enjoyed CVD, and it has helped

to solidify my interests in continuing to have a role

in science policy. While we did our best to get our

message across during each of our brief 15-minute

meetings, this is really just the start. As I was told

in a panel discussion the day before at the ESA,

the best way to ensure you have a long-term

impact on science policy is to form relationships

with the members of Congress and their staff by

communicating with them clearly and frequently

and by explaining the ways in which science

issues are relevant to them and the states they

represent. I plan to cultivate the relationships

I started at this 2014 CVD by writing follow-up

emails and letters, sending messages to members

of Congress on social media such as Facebook and

Twitter, and returning to participate in more CVDs.

I am most appreciative to the BSA for sponsoring

my visit; to the ESA, BESC, and AIBS for organizing

it; and to Morgan for coordinating my trip and

showing Megan and me around DC.

Morgan’s experience

This year I led a team, which was markedly

different from my experiences in 2012 and 2013.

Because this was my third time at the CVD, I was

able to share my experience from previous years

with new participants. My team included two other

graduate students from Arizona State University

and the University of Delaware. Our team met

with legislative aides and coordinators from seven

congressional offices, including both senators from

Arizona and Delaware, as well as Representatives

Carney (Delaware) and Sinema (Arizona, 9th).

I also met with a legislative correspondent from

Senator Mark Warner’s office (Virginia). The

week following our meetings, I heard back from

the legislative correspondent I met with that both

Virginia Senators (along with 19 other senators,

including both from Delaware as well) had signed

the Markey “Dear Colleague” letter requesting

increased appropriations for the NSF—it makes me

wonder if our meetings helped make this difference!

The most dramatic difference between the BESC

this year from my previous two years was the overall

nature of the meetings. Last year, the President’s

budget was released on the same day of the event,

so few members of Congress were familiar with the

specificity of the appropriations requests. Rhetoric

surrounding budget priorities was very heated and

the word “funding” had somewhat of a palpable air

of intrigue and suspicion surrounding it. This year I

detected much more of a need to communicate and

cooperate on the budget and a sense of urgency.

Among the legislative staffers our team met with,

all were specialists on science and technology

policy and included a former post-doctoral AAAS

Congressional Fellow. We were able to share stories

about how our work has touched the lives of not

only a local constituency, but also improves our

fundamental understanding of biological systems

at a global scale.

Despite the challenges and opportunities

observed during the CVD, it is satisfying

to realize the underlying support for basic

research and level of understanding among

many congressional offices that basic research

is not a partisan issue. What is most shocking is

the perspective I have gleaned over the past three

years as a participant in the CVD and how radically

attitudes toward funding for basic research can

shift from one year to the next. Despite the shifting

policy climate, the salience of our message remains

the same: basic research supports education

80

Plant Science Bulletin 60(2) 2014

and innovation priorities that help develop

our nation both uni- and multilaterally as a

leader in science and technology. A continued

commitment is necessary to maintain a leadership

role in basic research and it is our job, as botanists,

to communicate the importance of this role, its

breadth, and the interconnectedness we share with

both the biotic and abiotic features of the planet

that botanical research helps us better understand.

Already in the few weeks following the 2014

CVD, we have observed some positive response

to our message, including support in the Senate

for the Senator Markey “Dear Colleague”

appropriations letter and just two weeks ago,

the House voted to pass a bill supporting $7.4

billion for the National Science Foundation—not

quite the amount requested by CVD participants

($7.5 billion), but an increase of $154 million

from President Obama’s request for 2015.

What can you do?

Write to your congressional representatives, sign

up for Public Policy Reports from the American

Institute of Biological Sciences (AIBS, http://

www.aibs.org/public-policy-reports/), and become

involved! If you can’t make it to Washington, D.C.,

the AIBS organizes an annual event in August called

the Biological Sciences Congressional District Visits,

which gives scientists an opportunity to meet locally

with their representatives and senators to discuss the

importance of the work you do and federal funding

that supports it. Registration for the event is free and

should be opening soon! If you can’t attend in

person, remember that you can always write your

representatives and senators to ask for their support

and/or thank them if they already have supported

policy that is important to you!

Finally, if you are a graduate student or post-

doc, be sure to keep an eye out for these important

opportunities to engage in public policy, sponsored

by the BSA and our Public Policy Committee

(become a member!) You can expect a call for

proposals for the 2015 BSA Public Policy Award in

Fall 2014!

With deep gratitude to the BSA membership

for supporting important botanical education and

outreach, as well as the Public Policy Committee’s

commitment to improving opportunities for public

policy action,

—Megan Philpott, Steven Callen, and Morgan

Gostel

81

Plant Science Bulletin 60(2) 2014

The

American Journal of Botany continues Centennial

Celebration throughout 2014

The celebration of the first 100 years of the American Journal of Botany continues! The last issue of the

PSB featured interviews with some of the AJB’s most prolific authors over the years: Karl Niklas, Pam and

Doug Soltis, and Mark Chase. This issue features interviews with more members of this elite group, as the

following pages show.

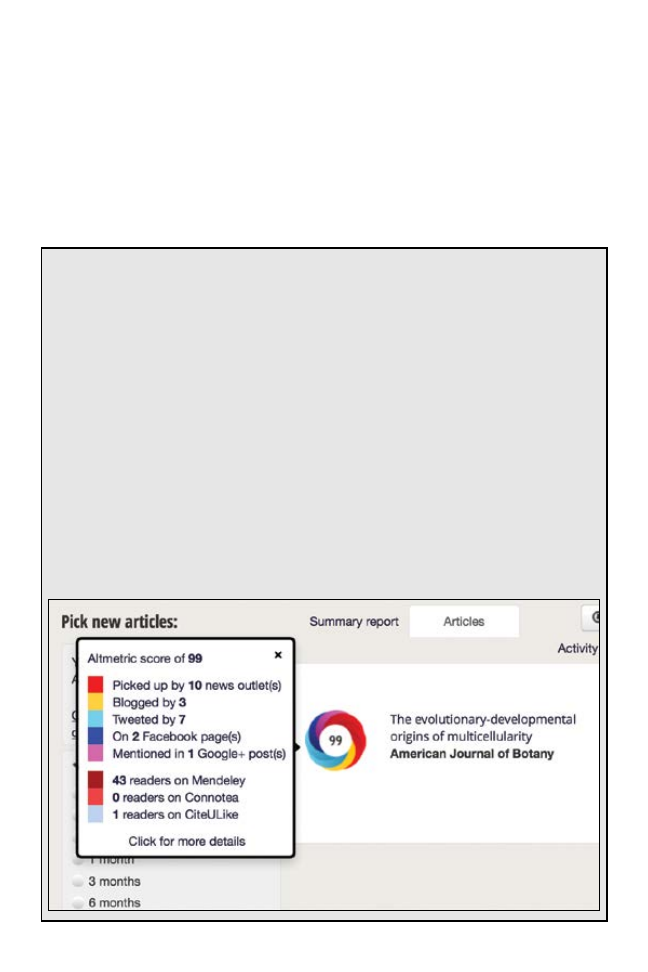

The AJB’s unique Centennial Review papers have also been attracting a lot of attention and positive

comments. These papers take a look at key research from the AJB’s past and re-examines and updates

the research to find where the field stands now and into the future. The following AJB Centennial Review

articles are already available and can be accessed for free:

• “Plant evolution at the interface of paleontology and developmental biology: An organism-centered

paradigm” by Gar W. Rothwell, Sarah E. Wyatt, and Alexandru M. F. Tomescu [101(6):899, 2014]

• “Is gene flow the most important evolutionary force in plants?” by Norman C. Ellstrand [101(5):757, 2014]

• “Repeated evolution of tricellular (and bicellular) pollen” by Joseph H. Williams, Mackenzie L. Taylor,

and Brian C. O’Meara [101(4):559, 2014]

• “The voice of American botanists: The founding and establishment of the American Journal of Botany,

‘American botany,’ and the Great War (1906-1935)” by Vassiliki Betty Smocovitis [101(3):389, 2014]

• “The nature of serpentine endemism” by Brian L. Anacker [101(2):219, 2014]

• “The evolutionary-developmental origins of multicellularity” by Karl J. Niklas [101(1):6, 2014]

• “The American Journal of Botany: Into the Second Century of Publication” by Judy Jernstedt

[101(1):1, 2014]

These articles are also hosted at www.botany.org/ajb100, and the site also hosts other free content---

nearly 1000 articles from the history of the AJB, as written by the journal’s top 25 contributors!

The AJB is one of the few surviving plant science publications published by a non-profit scientific society.

The journal, and its authors, reviewers, editors, readers, and subscribers, are at the heart of the Botanical

Society of America, and the strength of this connection makes the AJB stand out from many other journals.

82

Plant Science Bulletin 60(2) 2014

uniform floral development. Ann found mutants

of Melilotus alba that were non-papilionoid and

hence interesting to both of us; I supplied the SEM

work on it.

Why have you chosen AJB as one of the

journals in which you’ve published throughout

your career?

AJB has always been the premier American

journal in botany, in my opinion. I have had good

relations and help from all its editors from Norman

Boke (1970-1974) onward, mostly fair reviews,

and straightforward procedures toward publication.

The fact that the journal is so widely distributed

worldwide is also very important, since my areas

of research are practiced worldwide.

Shirley’s complete list of AJB publications, which

are free for viewing throughout 2014, can be found at

http://botany.org/ajb100/stucker.php.

Shirley Tucker, University of

California–Santa Barbara

Shirley Tucker has not only published 55 articles

in the American Journal of Botany over 55 years,

but has served as BSA President (1986-1987) and

Program Director (1978). She also won the BSA’s

highest honor, the BSA Merit Award, in 1989. We

asked Shirley to look back over her career and some

of the key research she published in AJB over the

years.

The first article you published in AJB was

“Ontogeny of the Floral Apex of Michelia fuscata”

in 1960. Take us back to that period—where were

you, what were you doing, and what were you

studying/most interested in at the time?

I was a Research Associate in the Botany

Department at the University of Minnesota,

supported halftime on my first NSF research

grant, which was on floral development in

Magnoliaceae. I had completed my PhD at the

University of California (Davis) and moved to

Minnesota with my husband Ken, where he

obtained a position in Entomology. Fortunately

I could work in the laboratory of Dr. Ernst Abbe,

with whom I had done an MS degree working on

Zea mays seedling development. Living material

of Magnoliaceae was scarce in St. Paul, but a small

tree of Michelia fuscata in a public greenhouse was

sufficient to produce four publications (all in AJB)

describing its vegetative and floral development as

well as its odd phyllotaxy. Meanwhile I was also

preparing my PhD work, on floral ontogeny in

Drimys winteri, for publication.

Your most recent article in the AJB was “An

open-flower mutant of Melilotus alba: Potential

for floral-dip transformation of a papilionoid

legume with a short life cycle?” in 2010. How

has the thread of your research changed over

time?

About 1983, my research interest turned

to legume flowers, at first investigating the

developmental distinctions among the three

subfamilies. Fifty-three publications on leguminous

floral ontogeny resulted, 26 of which were in the

AJB. Subfamily Caesalpinieae proved most diverse

in floral ontogeny, and I was fortunate in receiving

material for this work from west African tropics

from systematists. This paper by Ann Hirsch and

her students was among the few papers I published

on subfamily Papilionoideae, which had relative

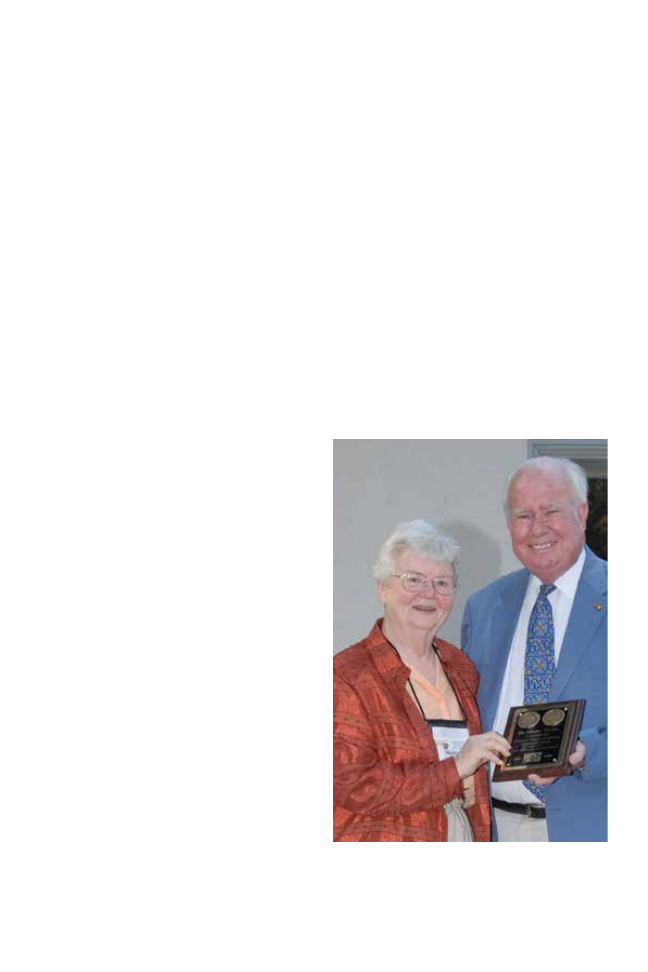

Shirley Tucker, accepting the BSA’s Centennial Award

in 2006 from Dr. Peter Raven. The award acknowl-

edged and honored outstanding service to the plant

sciences and the Society.

83

Plant Science Bulletin 60(2) 2014

and phylogeny from an organismal perspective,

and have employed development as a major focus

throughout. However, I did not ever expect to be

able to include information from molecular biology

and developmental genetics (no such thing for the

first 20-25 years) in my studies.

In looking back at all of the articles you’ve

published in AJB, which stand out and why?

This forces me to look back and remember what I

was thinking when each of the papers was accepted

for publication. I’ll choose my first paper, “Ontogeny

of the Paleozoic Ovule Callospermarion pusillum,”

because it allowed me to develop a new approach for

integrating developmental studies of extinct plants

with similar studies of living plants. It also was the

first project I conceived and implemented entirely on

my own (only one edit by Tom Taylor), and it gave

me confidence in my ability to do what I loved doing

for the rest of my life.

For the same reasons (and to emphasize that it

wasn’t all downhill from the first), I also really like

the 2005 article “Evidence of polar auxin flow in

375 million-year-old fossil wood” with Simcha

Lev-Yadun, which allowed us to begin inferring

the role of regulatory genetics in the growth and

evolution of extinct plants.

Why have you chosen the AJB as one of the

journals in which you’ve published throughout

your career?

The Botanical Society of America is my

organizational scholastic “home,” and the widely

read “house journal” is a natural for the audience

I wish to reach.

To delve deeper into Gar’s extensive research in the

AJB, please see his full list of articles at www.botany.

org/ajb100/grothwell.php

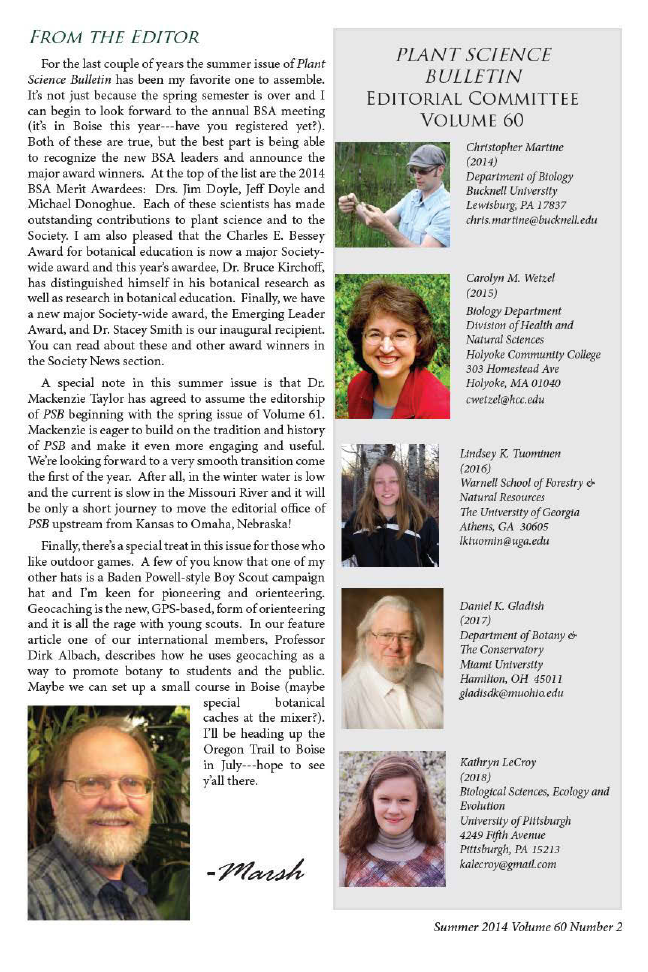

Gar Rothwell

Ohio State University and

Oregon State University

Gar Rothwell has been a prominent member of

the BSA for more than 45 years, and over that time,

he has published nearly 50 articles in the American

Journal of Botany---including his just-released AJB

Centennial Review article in the June 2014 issue. He

shared his thoughts about his research.

The first article you published in AJB

was “Ontogeny of the Paleozoic Ovule,

Callospermarion pusillum” in 1971. Take us

back to that period; where were you, what were

you doing, and what were you studying/most

interested in at the time?

I did that paper in the summer between my MS

and PhD studies at the University of Illinois at

Chicago when I had a short window of time to do

a study that others thought unlikely, but that I was

convinced could succeed.

Your most recent research article in the AJB

was “Seed cone anatomy of Cheirolepidiaceae

(Coniferales): Reinterpreting Pararaucaria

patagonica Wieland” in 2012. How has the thread

of your research changed over time?

The scope of my studies has broadened from

Pennsylvanian age, anatomically preserved fossil

plant structure, development, and evolution,

to fossil and living plants of all ages and modes

of preservation from around the world—but

otherwise it maintains the same basic emphasis.

In looking back over the course of your

research, what areas have you consistently

explored? What areas did you not expect to

explore?

I have consistently explored plant evolution

Gar Rothwell and his spouse, Ruth Stockey, fol-

lowing Gar’s American Journal of Botany Special

Lecture at BOTANY 2012.

Gar Rothwell at the 1975 Botany meeting.

84

Plant Science Bulletin 60(2) 2014

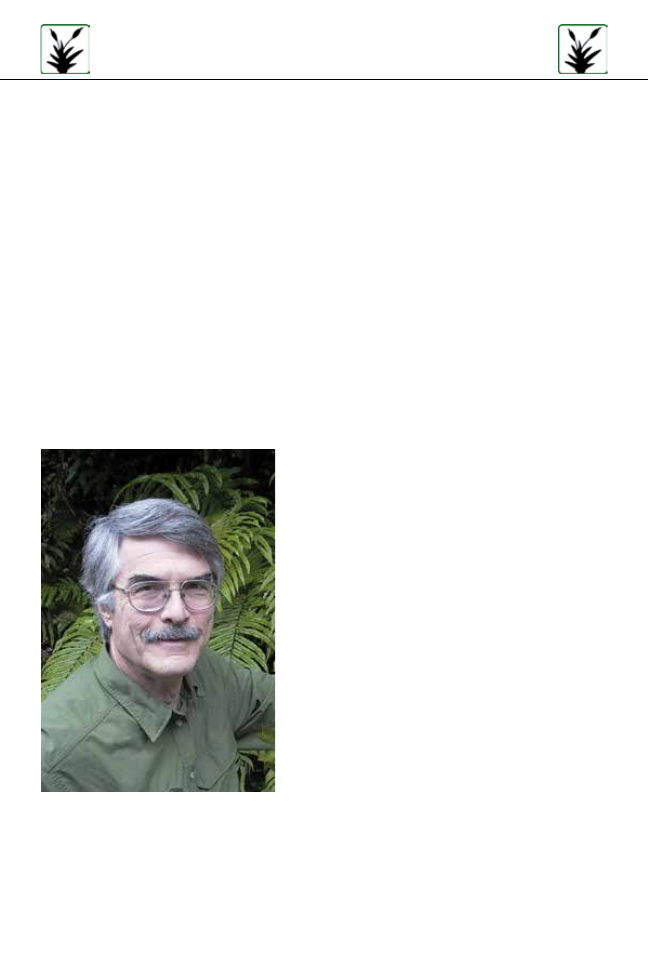

Daniel Crawford

University of Kansas

Dr. Daniel Crawford, who has served as BSA

President in 1996 and received the prestigious BSA

Merit Award, has been publishing in the American

Journal of Botany for nearly 45 years. He shared his

thoughts about publishing his systematics work most

prominently in the AJB over the years.

Your most recent article in the AJB was

“Invasive congeners are unlikely to hybridize with

native Hawaiian Bidens (Asteraceae)” in 2013.

Tell us a little about how systematics research

has changed since your first AJB article in 1971

(“Systematics of the Coreopsis petrophiloides-

Lucida-Teotepecensis Complex”).

One driver of change has been the availability

of new methods for generating data. In initial

studies in the ’60s and ’70s, the “new” data were

comparative secondary chemistry, with enzyme

electrophoresis and DNA not in the “tool kit” of the

plant systematist. New methods drove the direction

of research and the kinds of questions that could

be addressed. Of course, explicit methods of

phylogenetic analysis changed the thread of

research.

How has the thread of your own research

changed over this time?

Two constant themes have been studies of a

particular group of Asteraceae, tribe Coreopsideae,

and especially the genus Coreopsis, and the origin

and evolution of island plants. During my first eight

years on the faculty at the University of Wyoming, I

did not even contemplate studying plants of oceanic

islands, but interactions with Tod Stuessy following

the move to Ohio State initiated and nurtured a

long-standing interest in island plants.

In looking back at all of the articles you’ve

published in AJB, which stand out and why?

While it is difficult to select among articles

published in AJB, the two papers summarizing

allozyme diversity in native and endemic plants of

the Canary and Juan

Fernández Islands published in

2000 and 2001 are especially rewarding (

Francisco-

Ortega et al. “Plant genetic diversity in the Canary

Islands: a conservation perspective” and Crawford

et al. “Allozyme diversity in the endemic flowering

plant species of the Juan Fernández Archipelago,

Chile: ecological and historical factors with

implications for conservation”). Both articles are

the products of collaborative efforts with long-time

colleagues and friends in the U.S., Chile, and the

Canaries

. Also, both papers have discussions of the

conservation of the floras of the two archipelagos.

Why have you chosen AJB as one of the

journals in which you’ve published throughout

your career?

Since 1971, a substantial number of new journals

have been established, thus providing more places

to submit papers. Yet, AJB and Systematic Botany

have always been my two “home” journals, as I am

basically a botanist and a systematist. Also, AJB has

stayed with the trends in making the journal visibly

more attractive and in incorporating features such

as special issues centered on topics of current and

general interest.

Dr. Crawford’s complete list of AJB publications,

which are free for viewing throughout 2014, can be

found at http://botany.org/ajb100/dcrawford.php

Daniel Crawford in the late 1980s from Juan

Fernandez (Robinson Crusoe) Islands, placing plant

material into liquid nitrogen for use in allozyme and

DNA studies.

Daniel Crawford, 2014, at the University of Kansas.

85

Plant Science Bulletin 60(2) 2014

Paul Mahlberg

Paul Mahlberg has been a member of the BSA

since 1951—an incredible 63 years! In that time, he

has published 37 articles between 1961 and 2004. He

recently expressed his thoughts about his work over

his career.

The first article you published in AJB was

“Embryogeny and Histogenesis in Nerium

oleander. II. Origin and Development of the

Non-articulated Laticifer” in 1961. Please take

us back to that period: what were you studying/

most interested in at the time?

I chose for my doctoral study the non-articulated

laticifer, a most unusual cell type present in a small

number of angiospermous families. I became

intrigued by this cell from previous knowledge of it

during my earlier graduate studies (Master’s degree

in Botany, University of Wisconsin) and readings

of the classical literature on this cell type. When

I entered the Botany Department, University of

California, Berkeley (1954), and discussed a thesis

topic with Professor Adriance Foster, I selected this

cell type for my dissertation. Because the Oleander

(Nerium oleander L.) and Euphorbia marginata

Pursh. were generally available in the area, I

selected them as models for my study.

Perhaps I was intrigued most by the broad

questions of how a body cell could evolve into

such an unusual form, and what physiological and/

or genetic phenomena gave rise to its intrusive

growth capability. These broad questions remain

unresolved, in part perhaps because the techniques

were not yet available to provide full answers to

them. We learned many details about its features

but, as we know, answerable questions only lead to

new questions. I certainly would like to continue

this quest especially with the new techniques only

recently available that could probe deeply into

the laticifer proteins and genes associated with it

growth and differentiation.

Your most recent article in the AJB was “A

Chemotaxonomic Analysis of Cannabinoid

Variation in Cannabis (Cannabaceae)” in 2004.

How did the thread of your research change over

time?

My broadened interests in lipopilic secretory

cells and structures placed emphasis upon secretory

glands such as those in Cannabis, also a laticifer-

bearing plant. Our gland studies would focus on

electron microscopic examination of glands during

development and chemical analyses of the contents

within the gland. The distinguishing characteristics

for such a study required an extremely abundant

number and localized density of glands to facilitate

their electron microscopic examination, and glands

of large size and great numbers to probe individual

glands as well as their concentration so as to aid

examination of their structure and contents. I also

acquired a large number of accessions, nearly 200, of

Cannabis to research as a model for gland character

and analyses of their specialized lipophilic chemical

contents. Our studies linked cannabinoid synthesis

to the gland with its accumulation in the specialized

secretory cavity rather than in cells of the gland,

and the genetically defined cannabinoid contents,

in particular, to strains of distinct geographical

origin and distribution.

In looking back at all of the articles you’ve

published in AJB, which ones stand out and why?

My very first article provided the perspective

of the long-term, perhaps elusive, goal to identify

those factors that control the differentiation of this

unique cell type. It was a consideration of many

early biologically oriented scientists as attested in

the surprisingly extensive historical literature on

this cell type. Those early students of laticifer study

were unable to define the nature of this cell type.

They were unable to place it into perspective with

other cell types as they defined them within the

plant body. And I, too, remain unsatisfied in my

quest to elucidate those subtle factors that must

define the origin and development of this cell

among all other cells of the plant body. Detection of

Paul Mahlberg from the mid-1960s, shorty after

completing his PhD, on the campus of University of

Pittsburgh.

86

Plant Science Bulletin 60(2) 2014

other cells of the plant body. Utilization of recently

developed cell and tissue probes involving protein

and gene techniques, not available during our

previous studies, may elucidate the origin and

relationship of this laticifer among other cells of the

plant body.

But I do wonder at times—how could I still be

a part of such studies of this cell type? Perhaps I

still haven’t left the laboratory. It reminds me of the

axiom; there is so much to learn, and so little time.

Why have you chosen AJB as one of the

journals in which you’ve published throughout

your career?

I chose the American Journal of Botany for many

of our publications because I consider it a leading

journal in the field of botanical sciences. It has an

international reputation for publishing manuscripts

of the highest quality. I consider myself to be a

part of the Journal. Our Journal is international

in scope and is read by botanists throughout the

world. It utilizes the highest quality materials for

preparation resulting in excellent reproduction of

illustrations provided by authors. These qualities

contribute to making our Journal one of the finest

of international science journals.

Dr. Mahlberg’s complete list of AJB publications,

which are free for viewing throughout 2014, can be

found at http://botany.org/ajb100/pmahlberg.php

the laticifer as fossil laticifer structures, dating back

perhaps 50 million years, indicate that it originated

early in the evolution of angiospermy, but is limited

in its distribution among these plants.

I remain enthused that further studies on

laticifers, particularly the non-articulated form,

will elucidate its phylogenetic relationship with

Paul Mahlberg, 2013, enjoying retirement in Door

County, WI.

87

Plant Science Bulletin 60(2) 2014

Whitney R. Reyes Student

Travel Award provides funds

for BSA Hawai‘i Student

Chapter members to attend

Botany 2014 in Boise, Idaho

Whitney Reyes was a bright young scientist

whose enthusiasm and passion for botany inspired

many. She studied a variety of plants and had field

experience in many different ecosystems in Hawai‘i,

but those who knew her know that her favorites

were ferns and fungi. Whitney graduated with a

Bachelor’s degree in Botany from the University

of Hawai‘i at Mānoa in 2012, with several years of

research experience in the field and laboratory. She

is the coauthor of two peer-reviewed publications

on the ecology and restoration of the endangered

fern ‘ihi‘ihi (Marsilea villosa), in American Journal

of Botany and Restoration Ecology. Whitney was

the recipient of a BSA PLANTS Grant in its

inaugural year (Botany 2010 in Providence, RI).

She also presented her undergraduate research

at Botany 2012 in Columbus, OH. Whitney was

the co-founder and president of the BSA Hawai‘i

Student Chapter, and in its first year (2011) she

raised thousands in grant funds to give away native

Hawaiian plants at local festivals as public outreach

and education events.

Whitney passed away unexpectedly in October

2012 and is dearly missed, but she leaves behind

a rich legacy of botanical science, conservation,

and outreach. The Botanical Society of America

was very much her extended family, so it is fitting

to honor her with a travel grant that provides

young Hawaiian botanists the opportunity to

attend Botany meetings in the future. Officers

and members of the BSA Hawai‘i Student Chapter

worked hard to raise funds for this grant, both

locally and at national meetings, beginning with

Botany 2013. Many generous donations from BSA

national members have helped to fund this grant in

Whitney’s memory.

The Hawai‘i Chapter is pleased to announce

the first winners of the Whitney R. Reyes Student

Travel Award: Monica Dittbern (Senior, Botany

Major) and Jason Cantley (PhD Candidate in

Botany). They will have domestic airfare and

accommodation expenses covered, up to $1500

total, to attend Botany 2014 in Boise, ID, where

they will gain valuable experience, knowledge, and

opportunities to network with other BSA members.

The awardees will also give a short presentation

on their Botany 2014 experience at the first

BSA Chapter meeting of fall 2014, sharing their

experience with potential future BSA members. The

Hawai‘i Chapter would like to sincerely thank the

BSA membership for their support in the success of

the Whitney R. Reyes Student Travel Award.

—Dr. Marian Chau, Chair, Whitney R. Reyes

Student Travel Award Committee

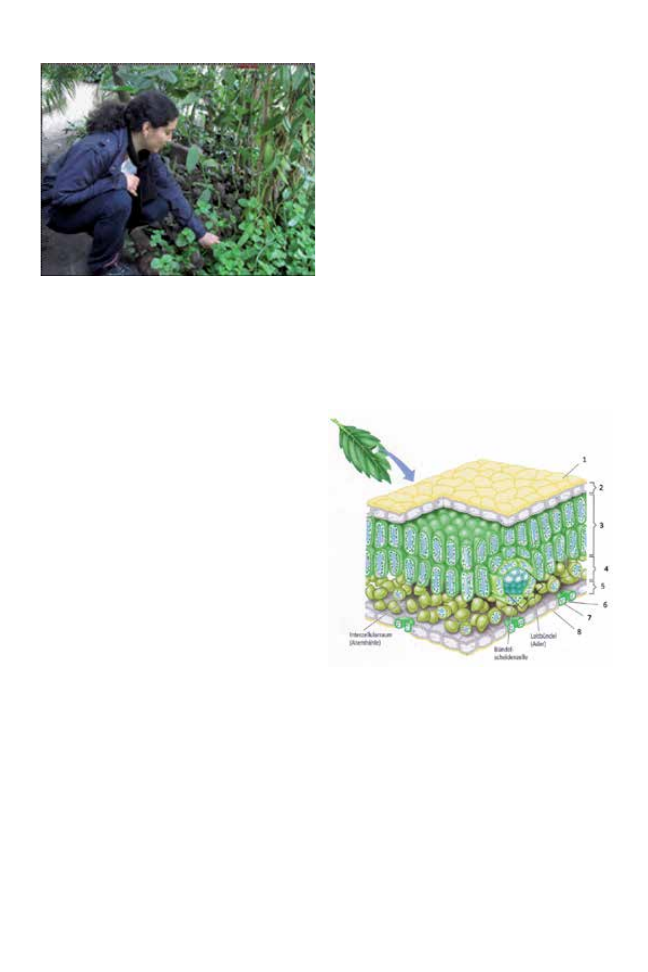

Whitney R. Reyes Student Travel Award winners:

Jason Cantley (PhD Candidate in Botany) and

Monica Dittbern (Senior, Botany Major). The

plants in the background are native Hawaiian hibis-

cus, koki’o ke’oke’o, Hibiscus arnottianus.

Photo by Marian Chau.

Whitney R. Reyes

88

BSA Science Education

News and Notes

BSA Science Education News and Notes is a quarterly update about the BSA’s education efforts and the

broader education scene. We invite you to submit news items or ideas for future features. Contact: Catrina

Adams, Acting Director of Education, at CAdams@botany.org or Marshall Sundberg, PSB Editor, at psb@

botany.org.

SOCIETY INITIATIVES AND

MEMBERS IN ACTION

USA SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING

FESTIVAL

BSA was well represented at the 2014 USA Science

and Engineering festival in Washington D.C. in

late April. The 3-day festival was enormous and

extremely well attended. Several thousand people,

including K-12 students and teachers, families, and

adults, stopped by our booth to learn about plants,

plant science careers, and PlantingScience.

Our volunteers entertained and educated an

almost constant stream of visitors, engaging them

with a choice of several activities. A “Guess the

Plant” scent-identification quiz was very popular.

(Cinnamon and coffee were the most recognized

plant scents, while rosemary stumped many!) Few

visitors were aware of plants’ use of chemicals

for defense against herbivores, and many were

surprised to learn how cinnamon bark is harvested.

Plastic fruits and vegetables were sorted hundreds

of times by visitors of all ages. Although visitors

often categorized tomatoes as fruits, bell peppers

and corn were very rarely placed in the same group.

Many visitors were shocked to learn how botanists

define fruits.

A plant evolution/phylogeny card sorting game

developed by Phil Gibson and Josh Cooper was

another popular activity used to teach very basic

plant evolution concepts. Sorting plant cards

by image, by a stylized representation of plants’

characteristics, and/or by a stylized molecular

code, visitors could experience how scientists

organize plants and construct phylogenies.

Fairhope Graphics (http://www.fairhopegraphics.

com), a neighboring booth offering a poster-sized

watercolor depiction of the phylogenetic “History

of Existing Life,” provided a serendipitous visual we

referred to often.

Chris Martine’s “Plants are Cool, Too” video

series was running on a screen for much of the

event, as well as a video series of “flashcards” for

identification of common plants of Manassas

National Battlefield Park courtesy of Greg Perrier.

We also gave some career advice and information

to students interested in botany, including a

parent of an undergraduate student considering

abandoning pre-med for a career in plant biology,

several high school students seeking college advice,

and a number of elementary-aged students who

were extremely enthusiastic about plants. The

PlantingScience program intrigued many K-12

BSA members Phil Gibson, Greg Perrier, Owen Schwartz, and Linda Franklin sharing their love of plants

with thousands of visitors at the USA Science and Engineering Festival.

89

Plant Science Bulletin 60(2) 2014

teachers in attendance, and we hope to recruit some

new teachers to the program as a result of the event.

“Wow, thanks! I learned something new today!”

was a constant refrain from visitors leaving our

booth, adults and children alike.

The booth would not have been possible

without the help of volunteers Josh Cooper, Linda

Franklin, Phil Gibson, Morgan Gostel, Kristen

Hoefke, Ingrid Jordan-Thaden, Amy Litt, Greg

Perrier, and Owen Schwartz. We’d also like to thank

members of the Education Committee who helped

with early planning for the event. We learned a lot

about logistics that will help us improve our booth

and plan engaging activities for the future.

PLANTINGSCIENCE

The PlantingScience team would like to thank

the many scientists who volunteered their time to

share their excitement about plant science with

the 200+ teams participating in PlantingScience

this spring. It makes such a difference for students

to have the opportunity to work with and get to

know scientists as they design projects. Here are

some thanks students and teachers offered to their

scientist mentors:

STUDENT THANKS:

“

I would like to thank you for all of your advice

to me and my team. You were a great helper to us!

I must say, our final conclusion was satisfying in a

way that we didn’t get what we were expecting and

learned something new about the growth of spores.

I had a great time working on the lab and your

advice was always useful. Thank you VERY much

for everything.”-greenhorse (The Herbivores)

“To wrap up the project, I would like to say how

happy I am to have this experience and participate

in such a cool project. I never would have fathomed

I would communicate with you and the students in

the Netherlands. Thank you for all your help and

advice throughout our experiments! The whole

project was really fascinating and I would like

to do more things like it. Thanks again!”-Gabby

(The Wolf Pack)

TEACHER THANKS:

“The kids have really enjoyed working with

the scientists this year—some actually checked

their page on a daily basis to see if their scientist

communicated with them. For several students

this experience was a total transformation—one

of my kids who was reluctant to complete anything

has been communicating with his scientist and

researching what his scientist works on so he can

ask his scientist. He also is a perfect, tuned in,

interested student. His grades are up all around

and he will be in my AP Environmental next year. I

love Planting Science!” -Ms. Lauer

“Hi Mentors! I wanted to thank all of you for

working with my kids! I have two very diverse

groups, but they’ve all enjoyed their time working

on this project...It has been a great learning

experience for the kids and for me, as well! Who

knows, perhaps you have inspired some future

plant scientists!” -Mrs. Buzzell

“Thanks to all the Mentors, Liaisons, and the PS

Team for everything you are doing to make science

class come to life for my students! My colleagues

have told me that they’ve been hearing students

talk enthusiastically about their projects in the

halls or in other classes! If they’re talking science

when they don’t even have to be, that must mean

the PlantingScience program is making a definite

impact! :)”-Ms. Schraeder

Student teams developed many excellent and

ambitious projects this spring. Many teams have

produced videos to present their project results

this session. This spring’s star project winners are

featured on the homepage of www.plantingscience.

org, so please stop by to see what the students have

been up to.

Mr. de Graaf has put together a video of

highlights from this spring’s Netherlands/Florida

class videoconference, viewable on YouTube:

http://youtu.be/e-gvWHNj4Es

Inquiring About Plants

e-book now on sale

The e-book Inquiring About Plants: A Practical

Guide to Engaging Science Practices by Gordon Uno,

Marshall Sundberg, and Claire Hemingway is now

available. All proceeds from the sale of the $9.99

e-book will benefit the PlantingScience program.

http://www.amazon.com/Inquiring-About-Plants-

Practical-Practices-ebook/dp/B00KI2GVD0/

90

Plant Science Bulletin 60(2) 2014

DON’T MISS BOTANY 2014: NEW

FRONTIERS IN BOTANY

An exciting number of education, outreach, and

training offerings for you to consider:

Sunday

•

Workshops on genomics, the PlantED

digital library, visual learning, developing

a hands-on distance education botany

lab course, incorporating the plant fossil

record into your botany course, software for

teaching plant ID, preparing digital images

for publication, and more.

•

Professional Development workshops for

students: Graduate School: how to apply

and what to expect; Crafting an effective

elevator speech and communicating

broader impacts of your work; networking

workshop for students and postdocs.

•

Firewise! Botany-in-Action Service Project

Tuesday

•

Vision & Change in Undergraduate Botany

Education, organized by J. Phil Gibson

Also, don’t miss the Teaching Section presentations

and posters, and the PlantingScience mixer. Check

the website for schedule updates. http://www.2014.

botanyconference.org

CHARLES E. BESSEY AWARD

Our congratulations to Bruce Kirchoff,

University of North Carolina, Greensboro, who is

the 2014 recipient of the Charles E. Bessey Award.

Please see the separate announcement on page 72.

UPCOMING OPPORTUNITIES

TO ENHANCE TEACHING AND

LEARNING

Attend the Society for the Advancement of

Biology Education Research (SABER)2014 National

Meeting, July 17-20 at the University of Minnesota,

Twin Cities, MN. Learn more at http://saber-

biologyeducationresearch.wikispaces.com/

National+Meeting+2014.

Make plans to attend the 2nd Life Discovery –

Doing Science Education Conference, October 3-4 at

San Jose State University in San Jose, CA. The theme

for this year’s conference is “Realizing Vision and

Change, Preparing for Next Generation Biology.”

Learn more about this upcoming conference at

http://www.esa.org/ldc/.

Team H2OMuchForYou from Springfield Central High School, one of 10 Star Project winning

teams of the Spring 2014 PlantingScience session.

91

Plant Science Bulletin 60(2) 2014

Mackenzie Taylor Named New Editor for

Plant Science Bulletin

Dr. Mackenzie Taylor (Creighton University) has agreed to assume the

editorship of the Plant Science Bulletin beginning in January 2015 with

Volume 61. Mackenzie has a strong connection to the Society, having

served on the Esau awards committee, the BSA investment committee,

the BSA strategic planning committee, and the AJB editor-in-chief search

committee. She also served as the first student representative to the BSA

executive committee.

Mackenzie is an excellent young researcher (PhD in 2011) with nine

published journal articles, including co-author of an AJB Centennial Review

article in the April American Journal of Botany, a book chapter and several education and outreach publications.

Dr. Taylor indicated that as a student she read every issue of Plant Science Bulletin “from cover to cover”