P

LANT

S

CIENCE

Bulletin

Fall 2014 Volume 60 Number 3

In This Issue..............

Rutgers University. combating

plant blindness.....p. 159

The season of awards......p. 119

Scientists proudly state their profession!

Botany 2014 in Boise: a fantastic

event......p.114

From the Editor

Fall 2014 Volume 60 Number 3

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

Editorial Committee

Volume 60

-

Marsh

Kathryn LeCroy

(2018)

Biological Sciences, Ecology and

Evolution

University of Pittsburgh

4249 Fifth Avenue

Pittsburgh, PA 15213

kalecroy@gmail.com

Christopher Martine

(2014)

Department of Biology

Bucknell University

Lewisburg, PA 17837

chris.martine@bucknell.edu

Lindsey K. Tuominen

(2016)

Warnell School of Forestry &

Natural Resources

The University of Georgia

Athens, GA 30605

lktuomin@uga.edu

Daniel K. Gladish

(2017)

Department of Botany &

The Conservatory

Miami University

Hamilton, OH 45011

gladisdk@muohio.edu

Carolyn M. Wetzel

(2015)

Biology Department

Division of Health and

Natural Sciences

Holyoke Community College

303 Homestead Ave

Holyoke, MA 01040

cwetzel@hcc.edu

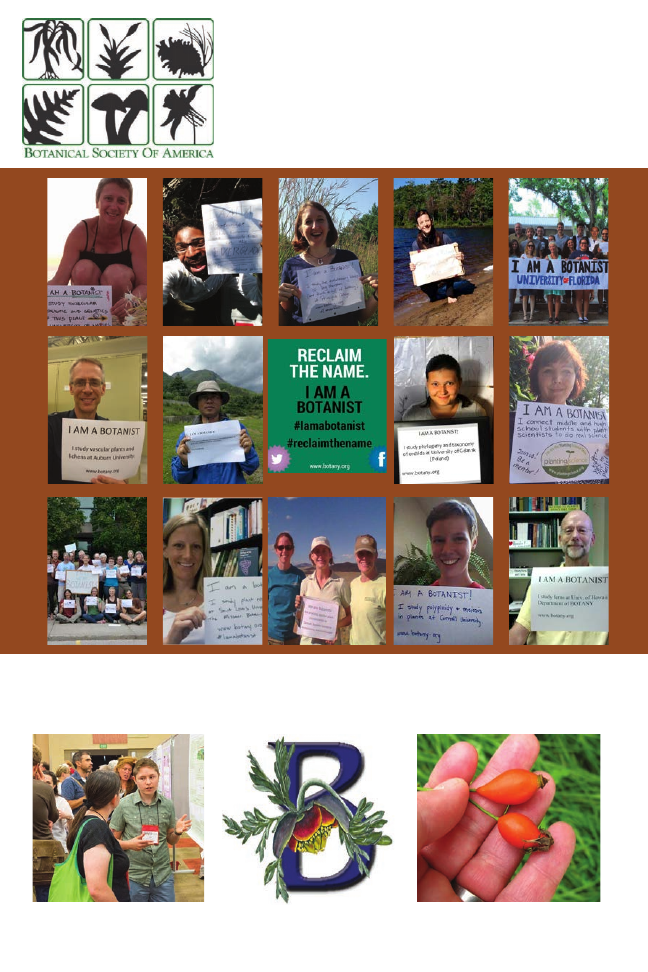

Reclaim the name: #Iamabotanist is the latest

sensation on the internet! Well, perhaps this is a bit of

an overstatement, but for those of us in the discipline,

it is a real ego boost and a bit of ground truthing. We

do identify with our specialties and subdisciplines,

but the overarching truth that we have in common

is that we are botanists! It is especially timely that

in this issue we publish two articles directly relevant

to reclaiming the name. “Reclaim” suggests that

there was something very special in the past that

perhaps has lost its luster and value. A century ago

botany was a premier scientific discipline in the life

sciences. It was taught in all the high schools and

most colleges and universities. Leaders of the BSA

were national leaders in science and many of them

had their botanical roots in Cornell University, as

well documented by Ed Cobb in his article “Cornell

University Celebrates its Botanical Roots.” While

Cornell is exemplary, many institutions throughout

the country, and especially in the Midwest, were

leading botany to a position of distinction in the

development of U.S. science.

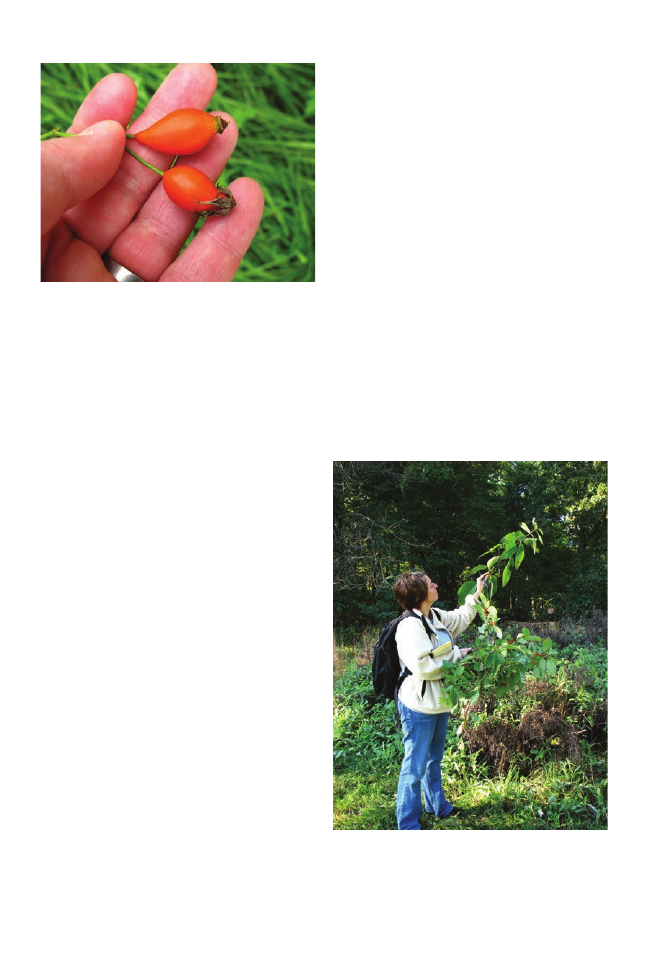

Beginning in the late 1930s and early 1940s a

serious disease began to appear in the U.S. that was

only diagnosed in 1998—PLANT BLINDNESS! In

hindsight, this serious disease was a major factor

in the steady erosion of botany and the status of

botanists. How can we overcome this epidemic

to help “reclaim the name”? Strong doses of local

treatment are indicated, and Lena Struwe and her

collaborators provide a good example of opening

students’ eyes in their article, “The Making of a

Student-Driven Online Campus Flora: An example

from Rutgers University.” Student engagement,

hands-on with plants, should provide the stimulus

for redeveloping plant sightedness—and a greater

appreciation for botany both within the scientific

community and with the public at large.

I’m sure that many of you have additional examples

d e m o n s t r a t i n g

effective treatment

of the insidious

disease, Plant

Blindness. I

encourage you to

share your results

by submitting a

manuscript to PSB.

113

Table of Contents

Society News

Annual Meeting ..............................................................................................................114

Awards .........................................................................................................................120

“Crowdfund” your research ............................................................................................123

BSA Science Education News and Notes ....................................................

125

Editor’s Choice ............................................................................................

127

Announcements

Personalia

ASPT Honors Chris Martine ................................................................................128

AIBS Releases New Science Advocacy Toolkit .............................................................129

National Cleared Leaf Collection ...................................................................................129

Funding Opportunities

American Philosophical Society ..........................................................................130

Bullard Fellowship ...............................................................................................130

Missouri Botanical Garden hosts Meeting of Ecological Restoration Alliance .............131

In Memoriam

Matthew H. Hils, 1955 - 2014 ..............................................................................132

Otto Ludwig Stein, 1925 - 2014 ...........................................................................132

AJB Celebration Continues .............................................................................................134

Reports

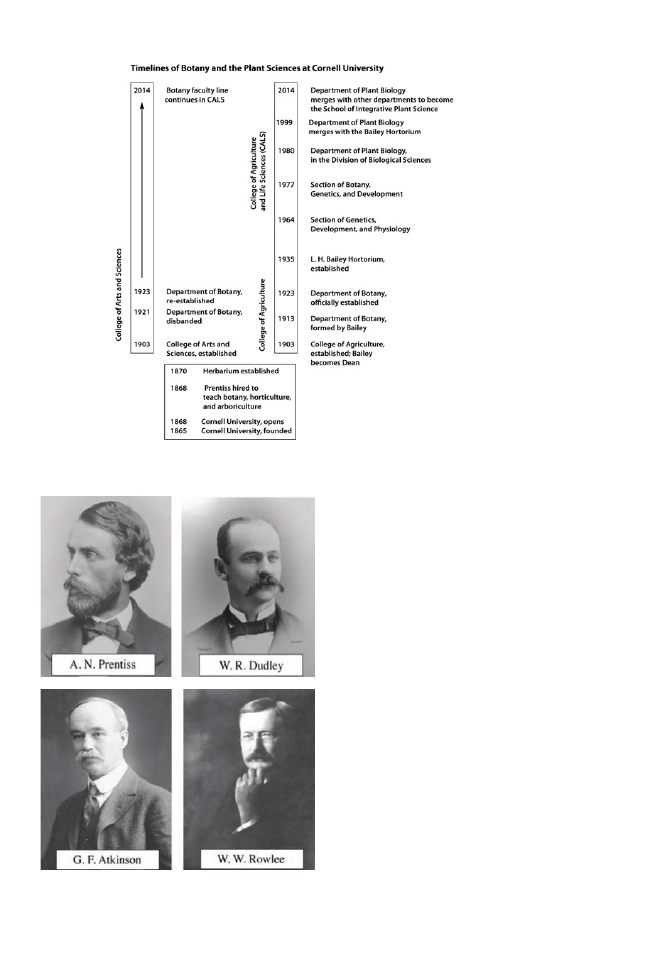

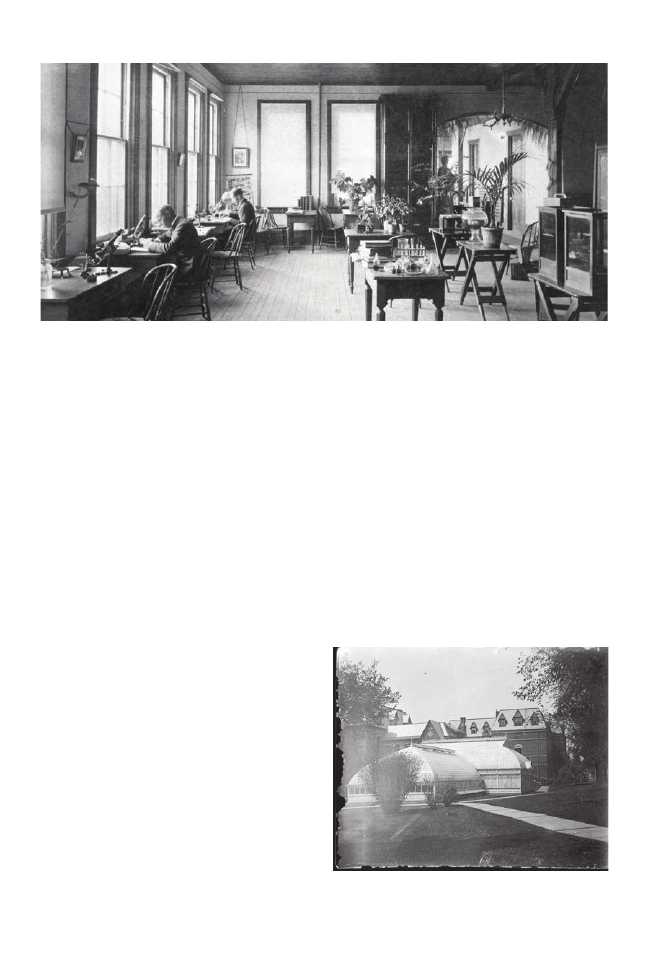

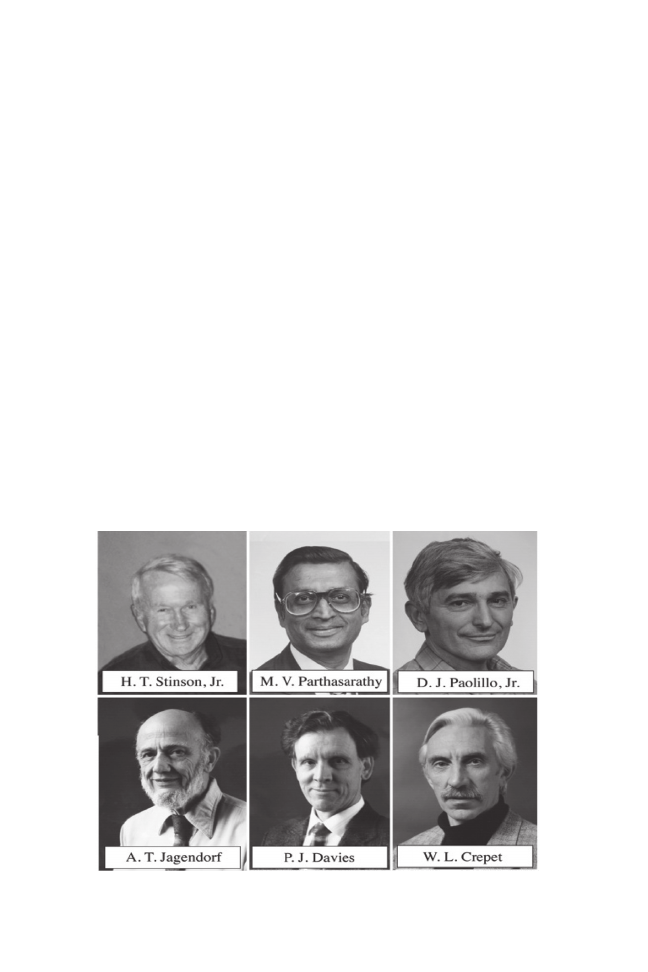

Cornell University Celebrates its Botanical Roots. ........................................................141

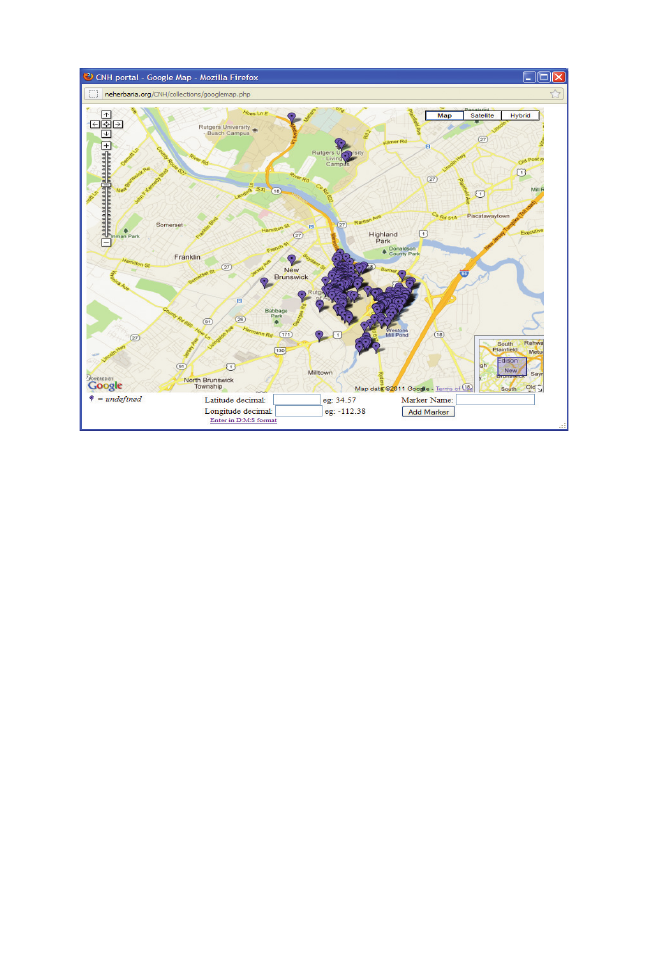

The Making of a Student-Driven Online Campus Flora: an example from Rutgers

University .............................................................................................................159

Book Reviews

Economic Botany ...........................................................................................................170

Systematics ....................................................................................................................174

Books Received ...........................................................................................

182

Science and Plants for People

Shaw Convention Centre

July 25 - 29, 2015

Submit your symposia proposal now at

www.botanyconference.org

114

Society News

BOTANY 2014 Conference

A Success

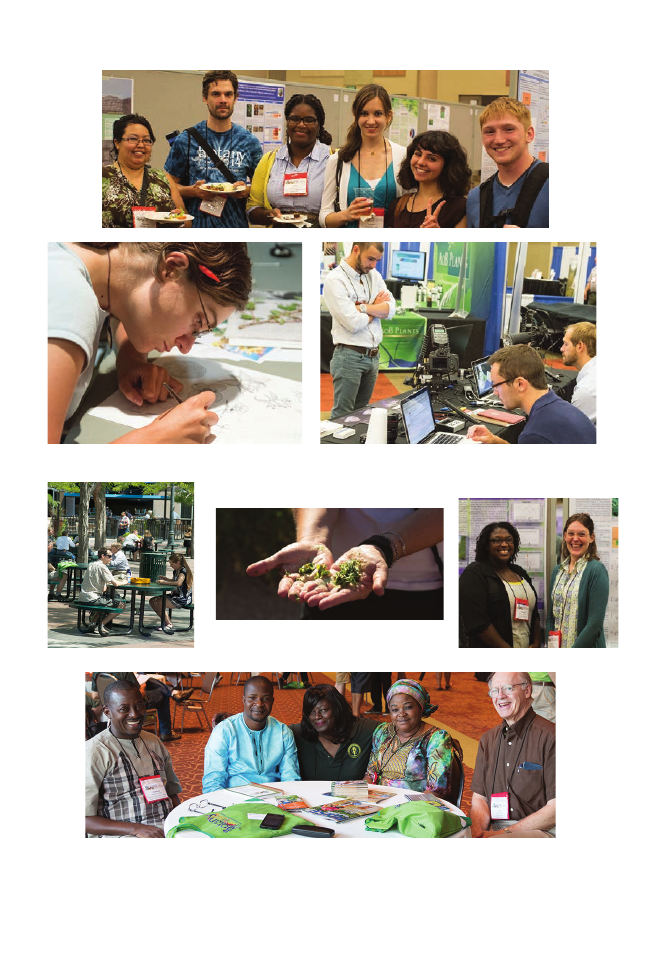

BOTANY 2014 in Boise was an amazing success,

with 1056 botanists from 49 states and 39 countries

in attendance. (From the United States, only

Delaware was missing!) The conference welcomed a

large international contingent, from China, Bhutan,

New Zealand, Nigeria, Vietnam, and more.

Boise rolled out the red carpet for the conference,

with stores displaying “Welcome Botany” signs in

windows throughout the city, and attendees were

enthusiastic about the cities welcoming ambiance,

safe and walkable venues, delicious and affordable

restaurants. The Boise Center and host hotel, The

Grove, provided not only great meeting sites, but

the important places for impromptu and planned

locations for the attendees to meet with each other.

One attendee described the conference as “an

explosion of science,” and another as the “single

week that keeps me excited and challenged

throughout the year.”

As always, the Exhibit Hall was popular, with

32 exhibitors on hand to bring some of the newest

industry information to conference attendees. And

the Poster Session was a wealth of information

from some of the up-and-coming young scientists

ready to present during the week-long conference.

The week started out with the traditional Botany

in Action service project—approximately 30

botanists put their backs into the work of weeding,

pruning and generally buffing up for “Firewise!”---

the program designed to teach citizens how to

design, plant, and care for their property so it

survives a wildfire.

That field trip, along with others, was well-

attended and popular. While some attendees went

out to enjoy Idaho’s spectacular weather, others

stayed in for an array of workshops designed to

hone professional skills.

This year, awards were given in a new format

called “Celebrate!” featuring a reception and an

informal ceremony, which replaced the banquet

from previous years. The mixer furthered the

meeting’s reputation for opportunities to meet and

network.

....The week is an an explosion of science....

115

Plant Science Bulletin 60(3) 2014

The 2014 Conference sets the stage for Botany 2015, July 25-29 in Edmonton, Alberta, with the theme

“Science and Plants for People.” The conference site http://www.botanyconference.org/ is now open for

symposia proposals.

116

Plant Science Bulletin 60(3) 2014

Conference Attendees Give

Back to Boise with “Botany in

Action” Service Project

Most scientific conferences feature lectures and

posters, but attendees rarely get a chance to actually

give back to the host city---but then, Botany

Conferences have always stood out for offering

above-and-beyond experiences.

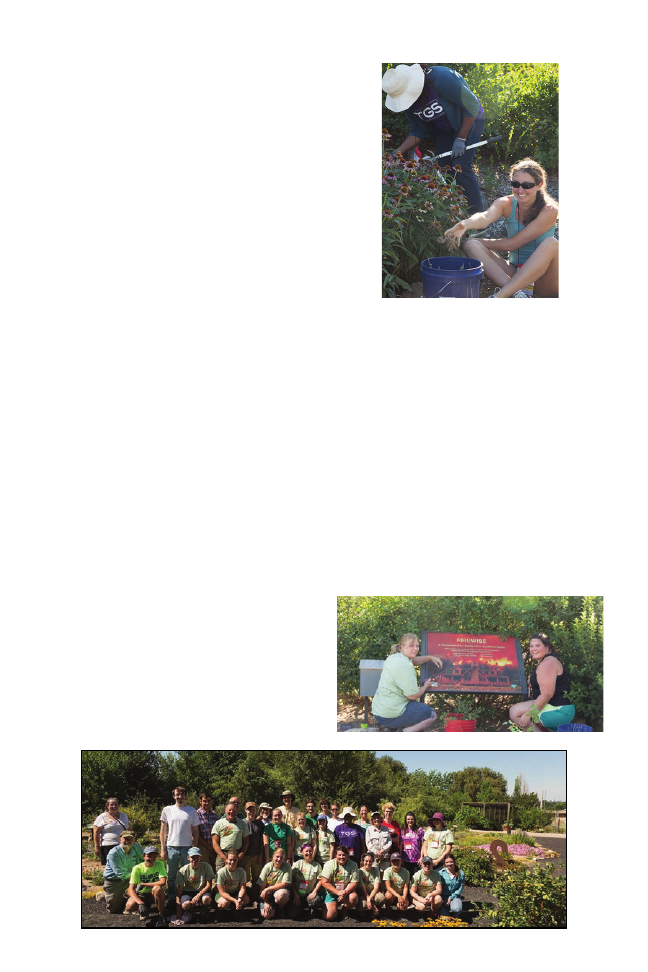

At Botany 2014 in Boise, more than 30 botanists

put their backs to work spiffing up the two-acre

Firewise Demonstration Garden during the Botany

in Action field trip. They descended on the flower

beds to weed, prune, and deadhead as well as

climb over the massive hill to remove the invading

weeds to once again render the hills fireproof.

The Garden—a cooperative project between the

Bureau of Land Management (BLM), the college

of Western Idaho Horticulture program, and the

Idaho Botanical Garden—is used to show the

public an example of how plantings can be used to

protect homes and property in the area.

The “before and after” was evident as the group

put their expertise to work, with the organizers of

the trip noting the difference between the “botany

volunteers” and some other groups, in terms of

their unwavering energy for the task.

It may have been more than energy, one volunteer

said. “We just know what we are looking at with the

plants. We know what to prune and where, how to

deadhead, what is a weed and what is a plant. That

makes the work fun for us. And we are learning

here too.”

The project, located adjacent to the Idaho

Botanical Garden, includes more than 350 native

and domestic species, all being evaluated for

performance and fire resistance in the Idaho

climate. The plants are watered in a drip system.

The Firewise project also focuses on teaching

residents about plant choice, maintenance, and

spacing, as well as how to plant in zones so that

structures do not burn. The concept of “defensible

space” is taught so that owners learn about planting

the right plants in the right place.

Roger Rosentreter, a botanist now retired from

the BLM and Boise State University who started

the Firewise project, coordinated the 2014 Botany

in Action for the Botany Conference. He explained

that today, perhaps with the onslaught of many

forest fires throughout the West, the idea of the

program is spreading. He says there is support from

the environmental community as well as the public.

“Landscaping and roofing materials will literally

determine if your house will burn,” Rosentreter

said. “What the public cares about is their houses.”

---Janice Dahl, Great Story!

117

Plant Science Bulletin 60(3) 2014

A (Much) Younger Crowd at Botany 2014

Botany 2014 attendees may have noticed a few younger-than-usual botanists in the mix this year. Here

are two stories of how the conference can affect those whose interest in botany has started early in life.

Youngest-Ever Presenters Win Physiological Section Award

High school students Eli Echt-Wilson and Albert Zuo were excited to be accepted to present their poster

at Botany 2014---but they never dreamed they would win the award for the best poster presentation in

the Physiological Section.

They developed their project, “Detailed Computational Model of Tree Growth,” working with mentor

and post-doc Sean Hammond and spurred to achieve more by their high school science teacher, Jason

DeWitte. DeWitte connected the students with Hammond, who started the tree modeling work. The two

students did the work as juniors at La Cueva High School in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

“Mr. Hammond told us about the Botany conference,” said Eli. “It is very exciting to be here,” chimed

in Albert. “People have been friendly and open to come up to our poster to talk about it.”

“The project started out as fun thing, a local challenge, but it snowballed and became something really

good,” Albert explained. “We just went with the flow!”

The young scientists entered their work earlier in the year in the Intel Science Fair and were delighted

to see one of the judges at the Botany conference. They found their own excitement growing at the

opportunity to attend presentations by scientists from all over the world.

With such a stellar performance, where do these young men plan to head in their careers? Both are

interested in computer sciences and how those are applied to other fields. Botany is definitely still in the

mix.

“I always wanted to be a scientist,” Eli said. “If I can apply com sci to botany or biology, it would be of

interest to me.”

“I would definitely come back,” said Albert with a smile, his fellow scientist adding, “We’re already

thinking about our next project.”

Eli Echt-Wilson and Albert Zuo, in the middle of filming a video presentation of their award-winning

Physiological Section poster.

118

Plant Science Bulletin 60(3) 2014

techniques for lifting the leaves from the rock.

“I grew up with my father being a scientist in

Los Alamos, a town of scientists, and was able to

feel the excitement my father had for discovery

and science,” Sarah said of the Botany Conference

experience. “Eagan was able to pick up on that and

feel it himself. That was the best/most a mother

could have hoped for and was not disappointed.”

Sarah said Eagan began collecting unusual plants

at age 4 with bromeliads, figuring out on his own

what that was. This year, he made several flower

gardens for his mother on Mother’s Day and has

created window gardens in every available space.

Already, Eagan has shown an interest in the loss

of plant diversity on the planet, though his mother

says he is not a prodigy botanist.

Sarah said she has worked to get her son

interested in other things, to make him better-

rounded. But his fascination with plants remains.

And perhaps, at the center of this ongoing discover,

the Botanical Society of America will help lead the

way.

---Janice Dahl, Great Story!

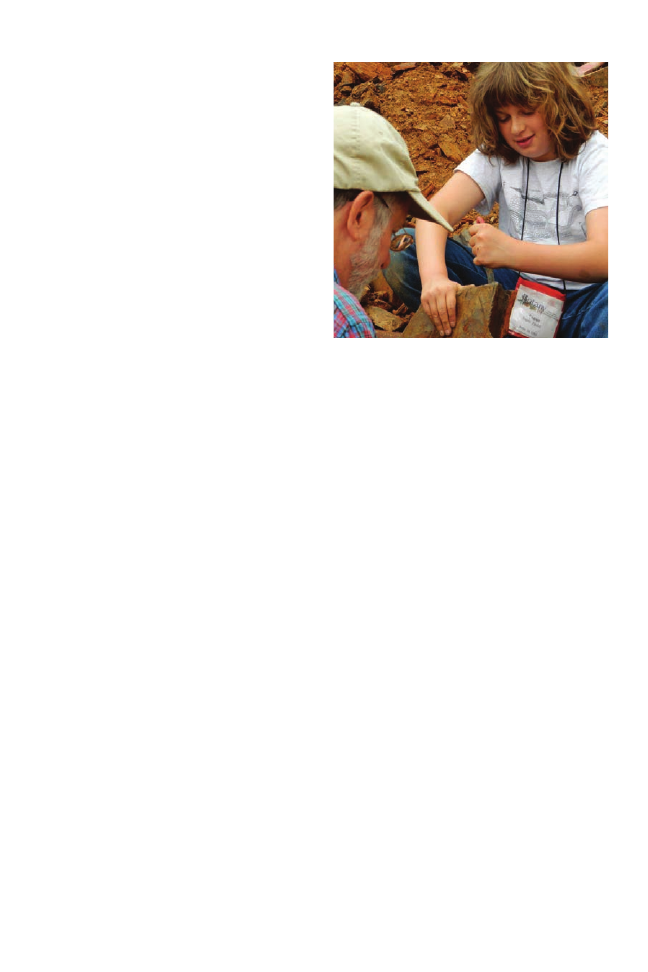

The Making of a Botanist

Although Botany conference organizers are

proud to have a large representation of students,

it’s rare when one of those students hasn’t even

entered high school. When 11-year-old Eagan

Brandenberger signed up for a Botany Conference

field trip, he and his mother Sarah Brandenberger

didn’t know quite what to expect---so perhaps they

were surprised to see world-renowned botanists

open their arms to someone so young.

Eagan talked about the many botanists on

the “Fossil floras associated with the Middle

Miocene Columbia River Basalts of Northern

Idaho” field trip who were eager to share their

help, showing him the plants and fossils. He saw

the professional botanists keeping drawings and

journal entries, and he kept his own journal during

the field trips. His mother said he started out by

drawing flowers, emulating the botanists he saw

doing the same, and then making notes about what

he saw. It’s something a bit unusual for 11-year-

olds, but maybe not for those headed so intently for

a career they’ve fallen in love with at such a young

age.

“The experience was amazing,” Eagan said,

talking about 50-million-year-old fossils he

unearthed on the three-day trip led by Dr. Steve

Manchester. Big leafs, little leafs, all different leafs

clustered on a rock just “this big,” he gestured in

excitedly explaining his discovery of fractured bald

Cyprus. “I was really looking for an avocado…but

I didn’t find it,” he added with the exasperation

reserved for pre-teens.

During the trip, they learned about geography,

stopping at Whitebird to discover fossils right at the

side of the road. Side by side with botanists, Eagan

learned how to split the rock, looking at each find

with fascination as each fossil was identified. The

scientists taught Eagan how to split the fossils from

the rock so that the entire rock doesn’t have to be

carried to preserve the fossil.

“(Field trip coordinator) Bill (Rember) was

showing me the leaf and I realized it wasn’t yet rock

or simply impression—but an actual organic leaf,”

Sarah said. Later, some of the participants invited

Eagan to “botanize” the wet lands, so they went and

checked out the flora of the wetlands and “freed”

some fossils from the dig. The botanists worked

with Eagan, Sarah said, showing him different

Eagan Brandenberger, 11, learning about plant fossil

identification during a Botany 2014 field trip.

119

Plant Science Bulletin 60(3) 2014

120

Plant Science Bulletin 60(3) 2014

Isabel Cookson

Award (Paleobotanical Section)

Established in 1976, the Isabel Cookson Award

recognizes the best student paper presented in the

Paleobotanical Section.

Kelly K.S. Matsunaga from Humboldt State

University, for the paper, “A whole-plant concept for

an Early Devonian (Lochkovian-Pragian) lycophyte

from the Beartooth Butte Formation (Wyoming)”

Co-author: Alexandru M.F. Tomescu.

Katherine Esau Award

(Developmental and Structural

Section)

This award was established in 1985 with a

gift from Dr. Esau and is augmented by ongoing

contributions from Section members. It is given to

the graduate student who presents the outstanding

paper in developmental and structural botany at

the annual meeting.

This year’s award goes to Rebecca Povilus, from

Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University, for the

paper “Pre-fertilization reproductive development

and floral biology in the remarkable water

lily, Nymphaea thermarum.” Co-authors: Juan M.

Losada and William E. Friedman.

Physiological Section

Li-Cor Prize

Christina Hilt, Fort Hays State University-

Advisor, Dr. Brian Maricle, for the poster

“Physiological responses of grasses to drought and

flooding treatments” Co-author: Brian Maricle

Maynard Moseley Award

(Developmental & Structural and

Paleobotanical Sections)

The Maynard Moseley Award was established

in 1995 to honor a career of dedicated teaching,

scholarship, and service to the furtherance of the

botanical sciences. Dr. Moseley, known to his

students as “Dr. Mo”, died Jan. 16, 2003 in Santa

Barbara, CA, where he had been a professor

since 1949. He was widely recognized for his

enthusiasm for and dedication to teaching and

his students, as well as for his research using floral

and wood anatomy to understand the systematics

and evolution of angiosperm taxa, especially

waterlilies (PSB, Spring, 2003). The award is given

to the best student paper, presented in either the

Paleobotanical or Developmental and Structural

sessions, that advances our understanding of plant

structure in an evolutionary context.

Fabiany Herrera, from the University of Florida,

Florida Museum of Natural History, for the

paper “Revealing the Floristic and Biogeographic

Composition of Paleocene to Miocene Neotropical

Forests “ Co-authors: Steven Manchester and Carlos

Jaramillo

Developmental & Structural

Section

Best Student Presentation Awards

Kelsey Galimba, University of Washington,

for the poster “Gene duplication and neo-

functionalization in the APETALA3 lineage of floral

organ identity genes in a non-core eudicot” Co-

author: Jesus Martinez-Gomez and Veronica S Di

Stilio

Ecology Section Student

Presentation Awards

Rachel M. Germain (Graduate Student),

University of Toronto, for the paper “Hidden

responses to environmental variation: maternal

effects reveal species niche dimensions” Co-author:

Benjamin Gilbert

Clayton J. Visger (Graduate Student), University

of Florida, Florida Museum of Natural History,

for the paper “Niche Divergence in Tolmiea

(Saxifragaceae): using Ecological Niche Modeling

to develop a testable hypothesis for a diploid-

autotetraploid species pair” Co-authors: Charlotte

Germain-Aubrey, Pamela S. Soltis, and Douglas E.

Soltis

Takashi Yamamoto, Chiba University, for the

best Graduate Student poster “Refugia might affect

the genetic structure of a sea-dispersal plants: Vigna

marina” Co-authors: Koji Takayama, Reiko

Nagashima, Yoichi Tateishi, and Tadashi Kajita

Ignacio Vera, for the best Undergraduate

Student poster “Comparing Seed Viability and

Harvest Consistency Across Sites and Years for the

Federally Endangered Plant Eriastrum densifolium

spp. sanctorum”

Davis Blasini, Chicago Botanic Garden,

for the best Undergraduate Student poster

“Introduction of Echinacea pallida in the Prairies

of Western Minnesota and its Possible Effects on

Native Echinacea angustifolia” Co-author: Stuart

Wagenius

Botany 2014 AWARDS

121

Plant Science Bulletin 60(3) 2014

Genetics Section

Student Presentation Award

Morgan Roche, Bucknell University, for the

poster “When dioecy doesn’t pay: Population genetic

comparisons across three breeding systems and five

species in Australia Solanum” Co-authors: Ingrid

Jordon-Thaden and Chris Martine

Physiological Section Student

Presentation Awards

Eli Echt-Wilson and Albert Zuo, La Cueva

High School - Advisor, Jason DeWitte, for the paper

“A Detailed Computational Model of Tree Growth”

Co-authors: Sean Hammond, David Hanson and

Jason DeWitte

Keri Caudle, Fort Hays State University

- Advisor, Dr. Brian Maricle, for the poster

“Pigment variation among ecotypes of big bluestem

(Andropogon gerardii) across a precipitation

gradient” Co-authors: Christina Hilt, Cera Smart,

Diedre Kramer, Sana Cheema, Loretta Johnson,

Sara Baer and Brian Maricle

Southeastern Section -

Association of Southeastern

Biologists, Poster/Paper Awards

Titian Ghandforoush, Wake Forest

University - for the ASB 2014 presentation:

“Phylogenetic reconstruction of relationships I the

paleotropical Vaccinieae (Ericaceae) based on DNA

sequence data” Co-author Kathleen Kron

Kristin Emery, University of North

Carolina at Asheville - for the ASB 2014 poster:

“Effects of open pollination, selfing, inbreeding and

outbreeding treatments on seed set and viability

in Spiraea virginiana, an endangered rose” Co-

authors Jennifer Rhode Ward and H. David Clarke

Developmental & Structural

Section Student Travel Awards

Italo Antonio Cotta Coutinho, Universidade

Federal de Vicosa - Advisor, Renata Maria Strozi

Alves Meira - for the Botany 2014 presentation:

“Diversity of secretory structures in Urena

lobata L.: ontogenesis, anatomy and biology of the

secretion” Co-authors: Sara Akemi Ponce Otuki,

Valéria Ferreira Fernandes, Renata Maria Strozi

Alves Meira

Roux Florian, INRA - Advisor, Jana Dlouhá - for

the Botany 2014 presentation: “Flexible juveniles or

why trees produce ‘low quality’ wood?” Co-authors:

Jana Dlouhá, Tancrède Almeras, Meriem Fournier

Rebecca Povilus, Harvard University -

Advisor, William E. Friedman - for the Botany

2014 presentation: “Pre-fertilization reproductive

development and floral biology in the remarkable

water lily, Nymphaea thermarum” Co-authors: Juan

M. Losada, William E. Friedman

Beck Powers, University of Vermont - Advisor,

Jill Preston - for the Botany 2014 presentation:

“Evolution of asterid HANABA TARANU-like genes

and their role in petal fusion” Co-author: Jill Preston

Ecology Section Student Travel

Awards

Rachel Germain, University of Toronto -

Advisor, Dr. Benjamin Gilbert - for the Botany 2014

presentation: “Hidden responses to environmental

variation: maternal effects reveal species niche

dimensions” Co-author: Benjamin Gilbert

Jessica Peebles Spencer, Miami University -

Advisor, Dr. David L. Gorchov - for the Botany 2014

presentation: “Effects of the Invasive Shrub, Lonicera

maackii, and a Generalist Herbivore, White-

tailed Deer, on Forest Floor Plant Community

Composition” Co-author: David L. Gorchov

Economic Botany Section

Student Travel Awards

Lauren J. Frazee, Rutgers University - Advisor,

Lena Struwe - for the Botany 2014 presentation:

“Urban Environmental Education and Outreach

using Edible, Wild, and Weedy Plants” Co-authors:

Sara Morris-Marano and Lena Struwe

Jacob Wasburn, University of Missouri -

Advisor, J. Chris Pires - for the Botany 2014

presentation: “Photosynthetic evolution in the grass

tribe Paniceae” Co-authors: James Schnable, Gavin

Conant and J. Chris Pires

Genetics Section Student Travel

Awards

Heather Dame, University of Ottawa - for

the Botany 2014 presentation: “Phylogeny of the

paraphyletic Fuireneae (Cyperaceae)” Co-authors:

Anna K. Monfils, Derek R. Shiels, Julian Starr,

David Pozo, Adriane L. Shorkey and Elizabeth R.

Schick

Robert Massatti, University of Michigan -

for the Botany 2014 presentation: “Microhabitat

differences impact phylogeographic concordance of

co-distributed species: genomic evidence in montane

sedges (Carex L.) from the Rocky Mountains” Co-

author: Lacey Knowles

122

Plant Science Bulletin 60(3) 2014

Rosa Rodriguez, Florida International

University - for the Botany 2014 presentation:

“Genetic structure, diversity, and differentiation

of Pseudophoenix (Arecaceae) in Hispaniola” Co-

authors: Brett Jestrow, Teodoro Clase, Francisco

Jimenez, Alan Meerow, Eugenio Valentin Santiago,

Jose Sustache, Patrick Griffith and Javier Francisco-

Ortega

Pteridological Section &

American Fern Society Student

Travel Awards

Alyssa Cochran, University of North Carolina,

Wilmington - Advisor, Dr. Eric Schuettpelz - for

the Botany 2014 presentation: “Tryonia, a new

taenitidoid fern genus segregated from Jamesonia

and Eriosorus (Pteridaceae)” Co-authors: Jefferson

Prado and Eric Schuettpelz

Jordan Metzgar, University of Alaska, Fairbanks

- Advisor, Dr. Stefanie Ickert-Bond - for the Botany

2014 presentation: “From eastern Asia to North

America: historical biogeography of the parsley ferns

(Cryptogramma)” Co-author: Stefanie Ickert-Bond

Jerald Pinson, University of North Carolina,

Wilmington - Advisor, Dr. Eric Schuettpelz - for

the Botany 2014 presentation: “Origin of Vittaria

appalachiana, the “Appalachian gametophyte”” Co-

author: Eric Schuettpelz

Sally Stevens, Purdue University - Advisor, Dr.

Nancy C. Emery - for the Botany 2014 presentation:

“Home is Where the Heat Is? Temperature and

Humidity Responses in a Fern Gametophytex” Co-

author: Nancy C. Emery

SPECIAL AWARDS:

Dr. Elizabeth Kellogg

Out-going BSA Past-President,

Danforth Center

The Botanical Society of America presents a

special award to Dr. Kellogg expressing gratitude

and appreciation for outstanding contributions

and support for the Society. Toby has provided

exemplary contributions to the Society in terms of

leadership, time, and effort.

Dr. David Spooner

Out-going Program Director,

University of Wisconson

The Botanical Society of America presents a

special award to Dr. Spooner expressing gratitude

and appreciation for outstanding contributions

and support for the Society. David has provided

exemplary contributions to the Society in terms of

leadership, time, and effort.

Dr. Linda Graham

Out-going Director-at-large

for Development, University of

Wisconson

The Botanical Society of America presents a

special award to Dr. Graham expressing gratitude

and appreciation for outstanding contributions

and support for the Society. Linda has provided

exemplary contributions to the Society in terms of

leadership, time, and effort.

Morgan Gostel

BSA Student Representative to the

Board, George Mason University

The Botanical Society of America presents a

special award to Morgan expressing gratitude and

appreciation for outstanding contributions and

support for the Society.

123

Plant Science Bulletin 60(3) 2014

well for increasing the number of potential donors

for one campaign, Experiment.com is structured

for a single principal investigator to launch a

campaign. This is something they are actively

working to change as numerous researchers have

requested for group campaign options.

If you already have a polished grant proposal,

this is a good place to a start. You will have to

modify it, though, dividing it into smaller sections

and removing ALL undefined technical language.

This will enable the public, particularly your friends

and family, to comprehend the importance of your

campaign and be motivated to contribute to your

science. A highlight of this alternative ‘open source’

research is that the backers (e.g. donors) receive

updates from you as your campaign progresses and

as your successfully funded project generates new

data. These updates are posted by the researcher,

and the website automatically sends an email to

donors saying that something has been posted that

they might be interested in. As with any company,

though, the backers agree to be part of this

community after they contribute until they remove

their email from the Experiment.com database.

Donors will continue to get notifications from

Experiment.com when other projects they might be

interested have been launched or are close to being

funded. In addition, researchers using Experiment.

com must agree to publish their research in an open

access journal.

The staff at Experiment.com will review your

campaign page multiple times until you and they

”Crowdfund” your research

What do you do when you have a great research

idea but can’t afford to pay for it?

One option is to “crowdfund” your idea using

Experiment.com, a small private company based

in the venture capital of the world, San Francisco.

From an office in the living room of a shared

apartment in the Mission District, the staff at

Experiment.com invited me to sit on a beanbag

chair on their deck and talk about my research. We

used Skype to bring Tommy Stoughton, my field

partner, into the discussion from the other side of

the state nearer Los Angeles. We focused on the

differences between a crowdfunding campaign and

a grant proposal, and the psychology of potential

donors. Following this conversation, we hashed

out a schedule and planned for the launch of our

crowdfunding campaign involving alpine plant

research.

It isn’t necessary that you make a personal visit to

establish a connection with the staff at Experiment.

com, but since I was in town, I wanted to meet

these folks in their element. The bare-essentials

living room had a large table with chairs around

and was crowded with computer equipment -- they

all slept in the apartment. Their job, and why we

hire them, is to help promote and manage your

social web-based presence to the World Wide Web

via Social Media in this new age of technology and

connectedness. They also manage the collection

of individual donations that are made to your

campaign, spending plenty of time encouraging

principle investigators (like us) to get out there and

find more backers.

Experiment.com is creating a different kind of

community of public involvement in the Scientific

Community. What most people ask is, “It is like

Kickstarter.com, but for science, right?” That is

exactly right. In the fall of 2013, Tommy Stoughton

launched his own all-or-nothing $20,000 campaign

on Experiment.com, but he ultimately received

nothing when his fundraising efforts fell short by

about $13,000. After great consideration regarding

how or why Tommy had failed, we received

encouragement to try again with a more realistic

goal. Tommy’s first attempt was designed to fund

an entire Ph.D. dissertation, not a small paper or

individual chapter. We decided to combine forces

and launch the campaign together as a team,

taking advantage of mostly non-overlapping social

network outlets. While this strategy might work

Ingrid Jordon-Thaden and Thomas Stoughton in

the Ruby Mountains, Humboldt National Forest,

Nevada.

124

Plant Science Bulletin 60(3) 2014

are confident that the public will understand your

goals and descriptions. It helps to make a video

of your research, your field trips, or even a small

dialogue of you talking about your goals. You

can repost this video on YouTube, for example,

providing information to link the video to your

campaign page. I posted our video before the

launch in order to prepare our network of friends

for the 30-day campaign.

When it really comes down to it, there were three

major sources of backers for our project: (1) our

contacts and posts on Facebook, (2) the Twitter

network, and (3) old-fashioned email, phone, and

personal communications. Immediately upon

launching the project, we sent individual emails

to friends, family and colleagues, asking them to

support our research. A high percentage of our

backers were people we already knew. In order

to entice an unknown science enthusiast, it’s best

to prepare interviews with journalists or bloggers

in advance, to promote your campaign before

it even begins. I was a bit late in that aspect, but

did arrange to have an article in my hometown

newspaper (The Omaha World-Herald) a few

days before our campaign ended. This did find a

few people who knew me as a child and reached

out to help. I can say that I spent approximately

10 hours a week in a 30-day period using my

communication outlets to encourage people to

donate. Tommy spent an equivalent amount of time

blogging and communicating with friends, family,

and others. Even though Experiment.com helps

with this aspect, they do not have access to your

personal contacts, and responsibility of promoting

your project lies almost entirely on you. Reflecting

again on Tommy’s first attempt to raise funds on

Experiment.com, having a slew of project backers

before the launch may be the quintessential key to

a successful crowdfunding effort. Project backers

attract more project backers as momentum builds

toward a 100% funded campaign.

We raised $7,170 in pledges. After a couple

of backers’ declined credit card attempts, and

Experiment.com’s 8% commission, we came

away with $6,593.80. This will cover our two field

trips this summer to the mountains of western

Montana, central Idaho, and the Yukon, Canada.

Any remaining funds will be used in the lab on our

newly acquired samples. We are already planning

a second campaign to fund the lab work we have

proposed for newly collected samples. We will likely

set a higher goal of $10,000 for this campaign, but

that number is not seen by the public right away. If

you are 100% funded before your campaign time

ends (set by the researcher to 30, 60, or 90 days),

this higher goal will be shown on your page as an

‘extension’ goal. Once a project has reached greater

than 100%, more members of the general public are

likely to chip in. We were funded 103%, but there

have been numerous successful projects that were

funded over 150%.

Overall, it has been a very positive experience

working with the team at Experiment.com.

Crowdfunding won’t replace grant-writing—

you can’t depend on the public and your family/

friends to continue funding your research—but

it can work once or twice as an excellent method

for generating preliminary data for larger grant

proposals. Crowd-source funding takes advantage

of the natural tendency of people to get excited

about scientific research. When a project is 85%

funded, for example, and you let people know

that you are progressing towards your goal, the

momentum can REALLY build. People talk about

your project, other backers chip in, the goal is met.

It is like an old-fashioned fundraiser at your school

or church, but with more technology and fewer

chocolate chip cookies... unless you want to try

your luck at Kickstarter.com and promise a rewards

like oatmeal raisin or external hard drives with all

the raw data.

---by Ingrid Jordan-Thaden, Bucknell University

125

BSA Science Education

News and Notes

BSA Science Education News and Notes is a quarterly update about the BSA’s education efforts and the

broader education scene. We invite you to submit news items or ideas for future features. Contact: Catrina

Adams, Acting Director of Education, at CAdams@botany.org or Marshall Sundberg, PSB Editor, at psb@

botany.org.

New and Ongoing Society

Efforts

PlantingScience Launches 17th

Session, Welcomes New Teachers

and Mentors

PlantingScience, the online mentoring program

started by the BSA in 2005, continues to reach

hundreds of students each session. Through

PlantingScience, plant scientists take advantage

of the opportunity to conduct K-12 outreach

from their own offices. They inspire middle- and

high-school student teams to do real science

investigations, to see themselves as scientists, and

to open students’ eyes to plants in their world.

We’d like to welcome the 30 new mentors

who have registered with PlantingScience since

last spring, and the 11 teachers who will use

PlantingScience in their classrooms for the first

time this fall. We also welcome back our dedicated

mentoring team, many of whom have been

mentoring for over 5 years.

We expect about 250 teams at 27 schools to

participate this fall, from 12 states in the USA as well

as from The Netherlands, Nigeria, and Indonesia.

By the end of the fall’s session we will have reached

well over 14,000 students with the program.

If you aren’t familiar with PlantingScience,

please stop by the website this session to see how

the teams are doing. We feature teams each week on

the homepage, www.plantingscience.org. If you are

interested in becoming a scientist mentor, please

apply! The time commitment is small, and you can

really make a difference in the students’ lives. We

are recruiting now for the upcoming spring session,

which will run from mid-February through mid-

April.

BSA is pleased to sponsor the following BSA

graduate students and post-docs as part of our

Master Plant Science Team this year: Jesse W.

Adams, Katie Becklin, Alan Bowsher, Riva

Bruenn, Steven Callen, Elizabeth Georgian, Tara

Caton, Julia Chapman, Taylor Crow, Cameron

Douglass, Rachel Hackett, Julie Herman, Cody

Hinchliff, Ingrid Jordon-Thaden, Irene Liao,

Daniel Blaine Marchant, Angela McDonnell,

Nora Mitchel, Mischa Olson, Rhiannon Peery,

Megan Philpott, Jerald Pinson, Adam Ramsey,

Amanda Tracey, Maria Vasquez, Evelyn Williams,

and Bethany Zumwalde.

Fundraising efforts continue as we strive to

expand and provide long-term support for this

successful program. A crowdfunding campaign

through the website www.Indiegogo.com is planned

for mid-September. Sales of the ebook Inquiring

About Plants: A Practical Guide to Engaging

Science Practices are going well. If you have not

gotten your copy of the e-book yet, you can learn

more and purchase a copy at www.plantingscience.

org. All proceeds support the PlantingScience

program.

Join us at the Life Discovery –

Doing Science Conference in San

Jose, California, October 3-4

The theme for this year’s Life Discovery

Conference (LDC) is “Realizing Vision & Change,

Preparing for Next Generation Biology.”

Designed as a “working conference,” the LDC is

organized to maximize interaction and exchange

among participants. The conference features 2

keynote speakers, 30 short presentations of best

practices in Biology education, 9 workshops and

more than 30 Education Share Fair Roundtable

discussions over the 2 days of the conference.

Additionally, there will be time for discussion

and networking by special interest groups. All

are welcome to bring your ideas and solutions to

advance Biology education in the 21st century.

Learn more and register here: http://www.esa.

org/ldc/2014-ldc-conference/information/

126

Plant Science Bulletin 60(3) 2014

Apply now for Upcoming Gordon Research Conference on

Undergraduate Biology Education Research (UBER) - July 12-17, 2015, Bates

College, Maine

Join a stellar group of colleagues from across the nation to advance our understanding of what it takes to

change undergraduate biology programs systemically and to catalyze novel directions for future research

at this new Gordon Research Conference.

The specific goals of the conference are to:

• Bring together a diverse community of biologists, biology education scholars, disciplinary society

leaders, and others to discuss current issues, drivers, trends and future directions in undergraduate

biology education research.

• Exchange information and ideas about best practices and their implementation.

• Foster development of new research ideas and collaborations among attendees.

• Develop a longer-term vision for regular UBER GRC meetings.

Applications for this meeting are currently available at: http://www.grc.org/programs.aspx?id=16908

www.plantingscience.org

127

Two of the articles explore “plant blindness,”

the concept developed by the late BSA member

Jim Wandersee to describe the public’s failure to

notice or appreciate plants. In “Attention ‘Blinks’

Differently for Plants and Animals,” Benjamin

Balas and Jennifer L. Momsen demonstrate that

there is, in fact, a fundamental difference in how

the visual systems of college students process plant

images versus animal images. They suggest several

useful strategies for overcoming zoocentrism.

Janice L. Anderson, Jane P. Ellis, and Alan

M. Jones use drawings of plant structures to

examine plant blindness in school students. In

“Understanding Early Elementary Children’s

Conceptual Knowledge of Plant Structure

and Function through Drawings,” the authors

demonstrate that young children have a basic

knowledge of plant structure and some functions,

but also identify some common misconceptions.

They conclude that drawings are a very useful tool

for assessing student understanding at this level.

In “An Evaluation of Two Hands-On Lab Styles

for Plant Biodiversity in Undergraduate Biology,”

John M. Basey, Anastasia P. Maines, Clinton D.

Francis, and Brett Melbourne describe two very

basic modifications to incorporate more student-

active learning into a traditional biodiversity course.

Finally, Jennifer Rhode Ward, H. David Clarke, and

Jonathan L. Horton, in “Effects of a Research-Infused

Botanical Curriculum on Undergraduates’ Content

Knowledge, SEM Competencies, and Attitudes

toward Plant Sciences,” describe the benefits of

incorporating plant-based field and laboratory

research throughout the undergraduate curriculum

at their institution, a public liberal arts college,

beginning with the introductory sophomore level

course and extending throughout the curriculum.

They provide some useful suggestions for keeping

the time demand manageable for faculty members.

The Plant Sciences Education issue of CBE-Life

Sciences Education [13(3)] is live at http://www.

lifescied.org/content/current! CBE-Life Sciences

Education is online and open access, and this issue

features an essay on Plant Behavior, by Dennis W.C.

Liu of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute; a book

review of the children’s book, My Life as A Plant,

published by ASPB; and seven research articles all

linked by a pithy editorial by Diane Ebert-May and

BSA member Emily Holt titled “Seeing the Forest

and the Trees: Research on Plant Science Teaching

and Learning.”

Three of the articles report on original inquiry-

based instructional materials. “Connections

between Student Explanations and Arguments

from Evidence about Plant Growth,” by Jenny

Dauer, Jennifer Doherty, Allison Freed, and Charles

Anderson, focuses on understanding matter and

energy transformations during growth. Although

the study examines middle and high school

students, the results and suggestions are clearly

applicable to college freshman courses.

In “Beyond Punnett Squares: Student Word

Association and Explanations of Phenotypic

Variation through an Integrative Quantitative

Genetics Unit Investigating Anthocyanin

Inheritance and Expression in Brassica rapa Fast

Plants,” Janet Batzli, Amber Smith, Paul Williams,

Seth McGee, Katalin Dosa, and Jesse Pfammater

describe a 4-week inquiry focusing first on

quantitative inheritance and then effectively

integrating Mendelian genetics.

“Optimizing Learning of Scientific Category

Knowledge in the Classroom: The Case of Plant

Identification” by Bruce Kirchoff, Peter Delaney,

Meg Horton, and Rebecca Dellinger-Johnston,

describes the application of computer software

in an active-learning format to improve sight

recognition of plants. The experimental design

provides proof of concept of the tools Bruce has

developed and demonstrated at BSA workshops for

the past several years.

Editor’s Choice

128

ANNOUNCEMENTS

Personalia

The American Society of Plant

Taxonomists honored BSA Member

Chris Martine for his emphatic

teaching and social media

outreach

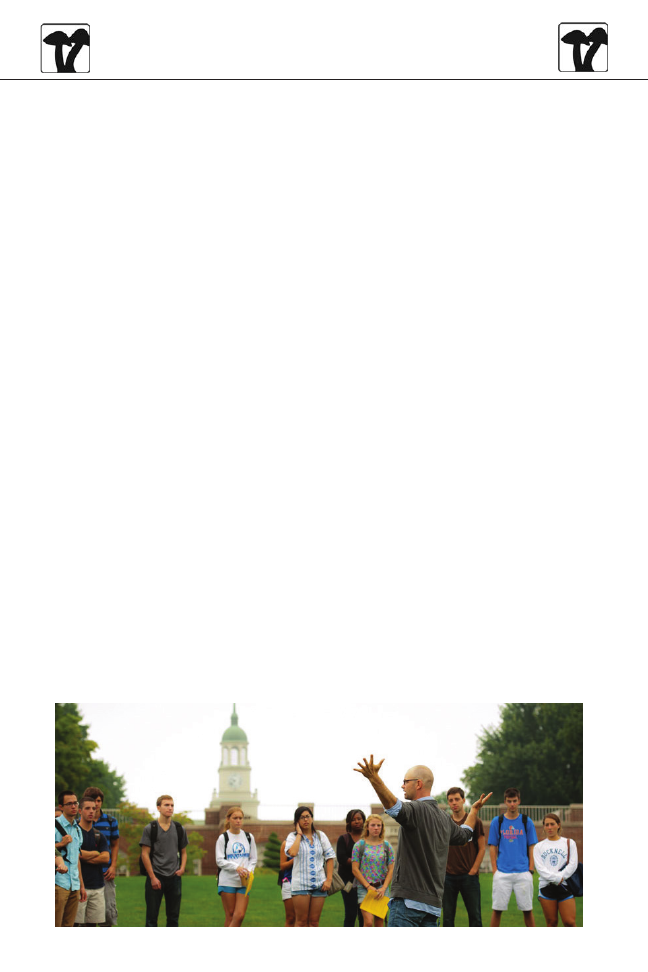

Teaching is like planting seeds. Lessons take root,

understanding grows and knowledge branches

out to new ground. Professor of Biology Chris

Martine has been planting seeds at Bucknell for two

years, and was recently honored for his efforts in

disseminating knowledge of the plant sciences far

and wide. The budding scientists he has nurtured

here too have garnered recognition for their own

research.

In May, Martine was honored by the American

Society of Plant Taxonomists with its Innovations

in Plant Systematics Education prize. The society

lauded Martine not only for his “contagiously

positive and fact-based way of enhancing botanical

learning especially among college undergraduates,”

but also for his efforts to reach a broader audience

through new and social media. Martine has more

than 1,600 Twitter followers (@MartineBotany);

blogs about plants, science and teaching for the

Huffington Post; and writes, produces and stars in

an educational YouTube series, “Plants are Cool,

Too!”

“People are using social media; people are

watching things on YouTube; people are reading

the Huffington Post,” Martine said. “I try to place

content where people are already spending time

watching things and reading things.”

Martine, the David Burpee Chair in Plant

Genetics and Research, said there’s a serious motive

underlying the entertaining, sometimes playful

content he posts.

“I’m really concerned about people recognizing

not only that biodiversity is declining on Earth, but

also that there is a lot of unknown biodiversity on

Earth that we still have a chance to discover,” he

said. “As a botanist, I try to use plants to help people

develop a greater appreciation for biodiversity,

nature and this sense of discovery that we still can

embrace. One of the things that makes plants an

ideal model for that sort of outreach is that they’re

everywhere—they’re really easy to find and they

don’t move.”

He also incorporates his online persona in the

classroom, whether by assigning his videos or

blog posts as homework, or casually suggesting his

students check out what he’s done next time they’re

hanging out in one of those virtual spaces.

The seeds of curiosity Martine has planted in the

minds of his students have clearly taken root. For

the second year in a row, three of Martine’s students

(Alice Butler, Ian Gilman and Morgan Roche)

were selected to receive Undergraduate Research

Awards by the Botanical Society of America (BSA),

the foremost group promoting plant sciences in

the United States. Last year the society parsed

out only six such grants to undergraduates, with

Bucknellians receiving half; this year it awarded

seven, with Bucknell students again earning three

grants. Three members of the Class of 2014—

Gemma Dugan, Anna Freundlich and Vince

Fasanello — were also honored with Young Botanist

of the Year awards, which recognize the cumulative

129

Plant Science Bulletin 60(3) 2014

accomplishments made by undergraduates during

their collegiate years.

“I get emails from [Chris] all the time saying, ‘I

heard about this; you should apply,’ and it’s always

something specific to my interests,” Dugan said. “He

pays a lot of attention to helping us as individuals

get what we want from our careers; he doesn’t just

forward everyone the same email. To have someone

who pushes you to apply for grants and scholarships

has been super helpful, and I think that’s why this

lab has been so successful.”

Martine is quick to note, however, that the

students wrote their own grant and scholarship

applications, and deserve final credit for their

accomplishments. He marked two additional

accolades garnered this year by his students

as particularly impressive. Gilman received an

Undergraduate and Graduate Student Training

Fellowship from the Torrey Botanical Society,

which he will use to attend a field course in the

Rocky Mountains through the University of Idaho.

“It’s an award that both graduate students and

undergraduates are eligible for,” Martine said. “It’s

hard to know what the pool was, but he likely

went up against graduate students as well as

undergraduates, and was chosen.”

Martine hopes his students and those he inspires

online will continue to nurture an interest in botany

as they move on. As they do, Martine will keep on

planting seeds, wherever he can.

“Everybody can find a plant,” he said. “Everybody

can learn something about one plant. That’s such an

easy jumping off point to help people develop an

understanding about nature, biodiversity and non-

human organisms.”

--Matt Hughes

AIBS Releases New Science

Advocacy Toolkit

The American Institute of Biological Sciences

(AIBS) has launched a new website to help

researchers participate in the development of the

nation’s science policy. This free online resource is

available at policy.aibs.org.

“AIBS has been a leader in its efforts to engage

scientists in public policy,” said AIBS President Dr.

Joseph Travis. “This new website continues this

important work by making it easier than ever for

researchers to be involved in the decision-making

process.”

The Legislative Action Center is a one-stop shop

for learning about and influencing science policy.

Through the website, users can contact elected

officials and sign up to interact with lawmakers.

The website offers tools and resources to inform

researchers about recent policy developments.

The site also announces opportunities to serve on

federal advisory boards and to comment on federal

regulations.

The Legislative Action Center is supported by

AIBS, the Society for the Study of Evolution, the

Botanical Society of American, and the Association

for the Sciences of Limnology and Oceanography.

The National Cleared Leaf

Collection-Hickey Published

Electronically

The Division of Paleobotany at the Peabody

Museum of Natural History is delighted to announce

the electronic publication of the National Cleared

Leaf Collection-Hickey (NCLC-H). The NCLC-H

consists of over 7,000 cleared, stained and mounted

extant leaves. It stands as the major community

resource in the area of foliar morphology for plant

systematists and paleobotanists around the world.

While at the Smithsonian Institution, Leo J. Hickey

began NCLC-H in 1969 as part of his research on

the systematic distribution of the leaf characters of

the flowering plants in relation to the evolution of

a group. The NCLC-H was moved to Yale Peabody

Museum on a long-term loan agreement when Leo

Hickey came to the Peabody Museum of Natural

History as Director in 1982. Sadly, Dr. Leo Hickey

passed away in February 2013. The NCLC-H was

returned to Smithsonian National Museum of

Natural History in May, 2014.

The NCLC-H is currently arranged alphabetically

130

Plant Science Bulletin 60(3) 2014

by family, then by genus and species. There are

approximately 321 families and 1,300 genera,

including herbaceous, parasitic, Arctic, alpine and

derived groups such as the Asteridae, in an effort

to elucidate the full range of dicotyledonous leaf

morphological patterns. Also, there are a significant

number of extinct and endangered species, such as

Canacomyrica monticola from New Caledonia.

The collection presently covers floras from South

America, North Central America, Oceania and Asia.

Most of the leaves have been taken from herbarium

collections, with some prepared using fresh or fluid-

preserved specimens. Each specimen is vouchered

to an authoritatively identified herbarium sheet.

The size, scope, documentation, and the quality of

the mounts make the NCLC-H the most important

database of leaf architecture in the world. At the

present time, the NCLC-H provides the main source

of documentation for the systematic description of

leaf architectural variationamong the dicotyledons

and has been the basis for the current system of

leaf architectural classification, fossil and modern

plant identifications, ecological and paleoecological

studies, as well as ongoing studies into the ontogeny

of leaf venation.

The electronic publishing of NCLC-H makes

researchers and the public easy access to the

database. The NCLC-H is available free at

http://

peabody.research.yale.edu/nclc/

.

---

By Shusheng Hu, Division of Paleobotany, Pea-

body Museum of Natural History, Yale University

Funding Opportunities

HARVARD UNIVERSITY BULLARD

FELLOWSHIPS IN FOREST RESEARCH

Each year Harvard University awards a limited

number of Bullard Fellowships to individuals in

biological, social, physical and political sciences to

promote advanced study, research or integration

of subjects pertaining to forested ecosystems. The

fellowships, which include stipends up to $40,000,

are intended to provide individuals in mid-career

with an opportunity to utilize the resources and to

interact with personnel in any department within

Harvard University in order to develop their own

scientific and professional growth. In recent years

Bullard Fellows have been associated with the

Harvard Forest, Department of Organismic and

Evolutionary Biology and the J. F. Kennedy School

of Government and have worked in areas of ecology,

forest management, policy and conservation.

Fellowships are available for periods ranging

from six months to one year after September 1.

Applications from international scientists, women

and minorities are encouraged. Fellowships are

not intended for graduate students or recent post-

doctoral candidates. Information and application

instructions are available on the Harvard Forest

website (http://harvardforest.fas.harvard.edu).

Annual deadline for applications is February 1.

American Philosophical Society

Announces Research Programs

Information and application instructions for all

of the Society’s programs can be accessed at http://

www.amphilsoc.org. Click on the “Grants” tab at

the top of the homepage.

Brief Information About

Individual Programs

Franklin Research Grants

Scope: This program of small grants to scholars is

intended to support the cost of research leading to

publication in all areas of knowledge. The Franklin

program is particularly designed to help meet the

cost of travel to libraries and archives for research

purposes; the purchase of microfilm, photocopies or

equivalent research materials; the costs associated

with fieldwork; or laboratory research expenses.

Eligibility: Applicants are expected to have a

doctorate or to have published work of doctoral

character and quality. Ph.D. candidates are not

eligible to apply, but the Society is especially

interested in supporting the work of young scholars

who have recently received the doctorate.

Award: From $1000 to $6000.

Deadlines: October 1, December 1; notification

in January and March.

Lewis and Clark Fund for

Exploration and Field Research

Scope: The Lewis and Clark Fund encourages

exploratory field studies for the collection of

specimens and data and to provide the imaginative

stimulus that accompanies direct observation.

Applications are invited from disciplines with a large

dependence on field studies, such as archeology,

anthropology, biology, ecology, geography, geology,

linguistics, and paleontology, but grants will not be

restricted to these fields.

Eligibility: Grants will be available to doctoral

students who wish to participate in field studies for

131

Plant Science Bulletin 60(3) 2014

their dissertations or for other purposes. Master’s

candidates, undergraduates, and postdoctoral

fellows are not eligible.

Award: Grants will depend on travel costs but

will ordinarily be in the range of several hundred

dollars to about $5000.

Deadline: February 1; notification in May.

Information about All Programs

Awards are made for noncommercial research

only. The Society makes no grants for academic

study or classroom presentation, for travel to

conferences, for non-scholarly projects, for

assistance with translation, or for the preparation

of materials for use by students. The Society does

not pay overhead or indirect costs to any institution

or costs of publication.

Eligibility: Applicants may be citizens or

residents of the United States or American citizens

resident abroad. Foreign nationals whose research

can only be carried out in the United States are

eligible, although applicants to the Lewis and

Clark Fund for Exploration and Field Research in

Astrobiology must be U.S. citizens, U.S. residents,

or foreign nationals formally affiliated with a

U.S. institution. Grants are made to individuals;

institutions are not eligible to apply. Requirements

for each program vary.

Questions concerning the Franklin and Lewis

and Clark programs should be directed to Linda

Musumeci, Director of Grants and Fellowships, at

LMusumeci@amphilsoc.org or 215-440-3429.

Missouri Botanical Garden

Hosts Meeting of Ecological

Restoration Alliance

(ST. LOUIS): Conservation experts from the

world’s leading botanical gardens met in St. Louis in

July and called for a renewed effort to link ecological

restoration with the elimination of poverty in

natural resource-dependent communities. In

Madagascar, for example, the Missouri Botanical

Garden provides training and jobs to local people

who in turn assist with ecological restoration. All too

often, there are no viable economic alternatives to

the degradation of biodiverse ecosystems. Member

gardens are committed to offering alternatives that

restore damaged land while providing income for

those living in these areas.

Botanical Gardens are uniquely qualified to

conduct ecological restoration given their expertise

in horticulture and their capacity to document the

source and genetics of plants. A garden’s reference

plant collection provides documentation of a

species even in areas with no remaining vegetation

so that ecosystems can be restored in a historically

accurate manner. Accurate species composition

is necessary to revitalize normal function and

regenerate ecosystem services such as watershed

protection and nutrient cycling.

The Ecological Restoration Alliance consists

of 18 member gardens from 10 countries. It was

formed in response to the United Nation’s Global

Strategy for Plant Conservation goal of restoring

15 percent of the world’s damaged ecosystems

by 2020. The Alliance is currently working to

restore more than 100 degraded, damaged or

destroyed ecosystems by 2020 including tropical

rainforests, temperate woodlands, grasslands,

beaches, wetlands and more through partnerships

with academic groups, industry and government.

Among those 100 projects are two managed by the

Missouri Botanical Garden: Restoring diversity in

the St. Louis Region and Preserving and Restoring

a Rich and Diverse Flora in Madagascar.

132

Plant Science Bulletin 60(3) 2014

In Memoriam

Matthew H. Hils

1955-2014

Matt Hils, Professor of Biology, Director of J.H.

Barrow Field Station, and Director of the Center for

the Study of Nature and Society at Hiram College,

passed away June 10, 2014 at his residence. Matt

received his B.A. in Biology from Thomas More

College, his M.S. from Miami University (OH), and

Ph.D. at University of Florida in Gainesville before

arriving at Hiram College in 1984.

Although Matt has made contributions to the

systematics of several flowering plant groups

(Saxifragaceae, Rosaceae, and Melastomataceae,

to name a few), he will be remembered best for

his legacy as a teacher, mentor, and friend to every

student who entered his class. In a time when a love

for Botany is waning in students, Matt’s unwavering

enthusiasm sparked a love for plants among so

many budding biologists. Matt was at his best

in the field, hand lens to one eye and mindful of

his students with the other. He taught many field

courses including Systematics of Vascular Plants in

the Smoky Mountains, Non-Vascular Plants on the

trails of the James H. Barrow Field Station, Field

Botany in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, A

Natural History of the Caribbean in Trinidad and

Tobago, and Natural History in the 21st Century in

the Galapagos Islands. Even on campus he taught

courses to inspire a sense of awe and wonder in

our inner naturalist, such as Ethnobotany and his

seminar On the Origin of Species.

Beyond his courses, Matt was a central member

of the Hiram College community. He served as a

faculty advisor for many in the Biology department,

and went above and beyond to know each student

in class. As a mentor, it was not uncommon to see

him at a sporting event cheering on his students, or

checking in with a student (former or present) that

he ran into on campus. As a friend, he transcended

academia in his availability to listen, help, and

laugh. His dedication to these roles was authentic

and transparent to all. Many of his students came

to him for guidance in coursework, life, and careers

regardless of their focus of study, and he gladly

made an effort to guide them toward their goals. An

avid cyclist, basketball enthusiast, and volleyball

fan, one could expect to see Matt around campus

and town any day, and he was always happy to see

you.

Thank you Matt, you will be missed but your

lessons and love will live on.

In lieu of flowers, memorial gifts can be made in

Professor Hils’ honor to the James H. Barrow Field

Station or Hiram College.

Otto Ludwig Stein

1925 - 2014

Otto Stein was born Jan. 14, 1925, in Augsburg,

Germany, and moved to Berlin when he was 8 years

old. He and his parents were protected by a local

policeman on Kristallnacht, Nov. 9-10, 1938, and

the family moved to the United States in January,

1940. He enlisted in the U.S. Army in September

1944 and after the war, he served as an interpreter

for the United Nations War Crimes Commission

and for the first four U.S. War Crimes Tribunals at

the former Dachau Concentration Camp.

Upon returning to the United States, Otto

attended the University of Minnesota through

the G.I. bill, obtaining a doctorate in botany

under Ernst Abbe. He completed a post-doctoral

fellowship at Brookhaven National Laboratory and

joined the botany department at the University of

Montana at Missoula.

Coming from Indiana, I first met Otto as a

beginning graduate student at Montana. Otto was

never shy or timid about anything, but he had a

compassion for seeing that everyone did their best.

133

Plant Science Bulletin 60(3) 2014

sectioning 96 corn seedlings, I had the disastrous

experience of seeing all my serial sections float off

the slides because of defective Haupt’s adhesive. I

was devastated. After repeating the experiment,

Otto’s compassion exuded as he helped me section

another 96 seedlings. That was Otto.

In Otto’s lab, my graduate student colleague,

Elisabeth Baker Fosket (wife of Don Fosket)

and I constantly would hear Otto expressing his

displeasure with someone, male or female, by

stating “I’m going to castrate you with a dull spoon!”

So Betsy Fosket and I made a beautiful plaque

with a large wooden spoon and a shiny brass label

entitled “THE DULL SPOON.” We wrapped it up

and interrupted his botany lecture and presented it

to him in front of 200 students. Some immediately

asked what does it say and what does it mean? He

unabashedly told them, and said that he would use

the spoon on these two graduate students after the

lecture! The plaque still hangs above his office at

UMass.

For me and others, Otto was a superb analyst

and critic with compassion to urge everyone to do

their best. He was a great mentor to me and any

success I have had as an educator and researcher, I

owe to Otto. I cherish the long friendship and close

relationship we maintained through the past 50

years. We all continue to celebrate his contributions

to botany and humanity.

—David Dobbins, Professor Emeritus, Millersville

University of Pennsylvania.

You had to know this to understand Otto and I

relate some examples. While a first-year graduate

student, I was learning how to use the microtome

for a research project. At one point Otto yelled at

me because I was not doing something right. He

saw my startled and astonished expression and then

sat down beside me to explain his yelling. He said,

“I will tell you twice about something, but the third

time I yell.” I responded that he yelled at me the first

time and he replied, “I am getting older and don’t

have time for the first two, so I go straight to the

third time.” That was Otto.

After my microtome experience, I entered his

office and indicated I would like to do my graduate

studies under his advisement. He said, “I don’t

take graduate students I know nothing about.”

He plopped a book on his desk that was Edmond

Sinnott’ s Plant Morphogenesis and said I should

read it and then come see him. I took the book and

in 3 days had read it from cover to cover. Returning

it to him on the third day, he asked if I had read

it. I said yes, all of it. Unsure I had done that, he

asked what was on page 100? I responded that it

showed the experiment by Vochting on polarity

of root/shoot formation in willow twigs. He

looked astonishingly at page 100 (which had that

description) and said, “That’s it. You can be my

graduate student.” I knew what was on page 100

because, in those days, libraries stamped their seal

on page 100 of books. I never told him why I knew

what was on page 100.

Sometimes it was difficult to predict what Otto

would say or do. While I was taking an exam in Plant

Systematics, he tapped on the door window and

called me out to say he was leaving the University

of Montana for the University of Massachusetts

and I could either finish my degree at Montana

or transfer to Massachusetts and to let him know

my decision the next morning. After lamenting all

night about what to do, I entered his office bleary

eyed and declared I had decided to transfer to

UMass. He responded by asking me to give him

nine reasons I wanted to transfer! Unprepared for

that question, I fumbled around for nine reasons

and evidently satisfied him. Thus our relationship

continued through the years at UMass.

Otto had a compassion that endeared me to him.

In my Masters research I had done an experiment

involving effects of heavy water (D

2

O) on the

growth of corn seedlings. The experiment involved

making growth measurements every 2 hours for

48 hours. I slept in the lab for 2 days. After serial

134

Plant Science Bulletin 60(3) 2014

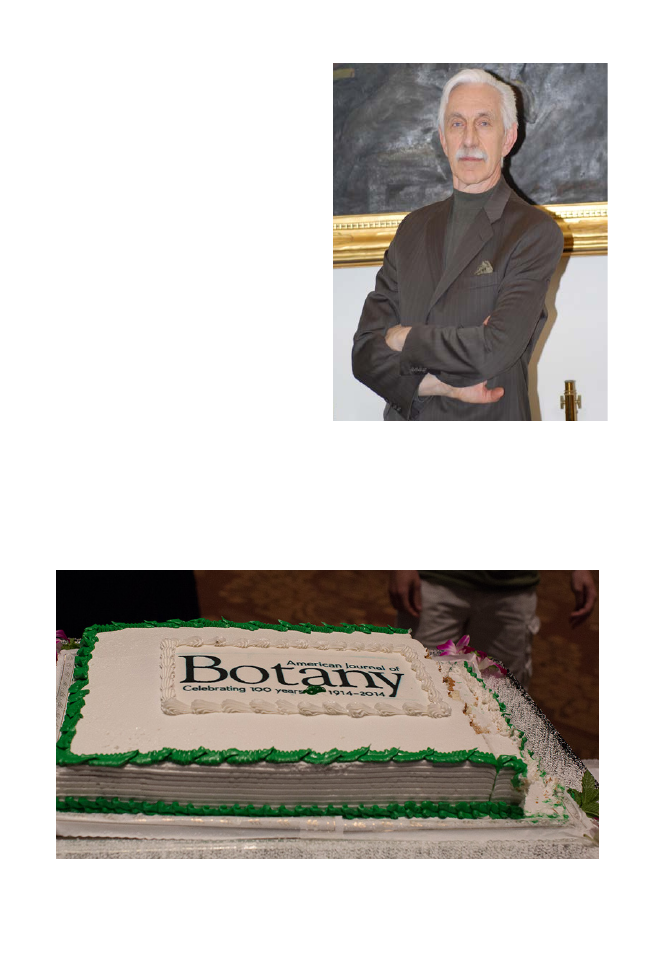

The American Journal of Botany Centennial Celebration

Continues through out 2014

The celebration of the first 100 years of the American Journal of Botany continues! The first two issues of

the PSB this year have featured interviews with some of the AJB’s most prolific authors over the years, and

this issue features interviews with more members of this elite group, as the following pages show.

The AJB has been promoting its anniversary with the special Centennial Review papers, which have

appeared every month this year. These papers take a look at key research from the AJB’s past and re-

examines and updates the research to find where the field stands now and into the future. The following

AJB Centennial Review articles are already available and can be accessed for free:

• “The relative and absolute frequencies of angiosperm sexual systems: Dioecy, monoecy, gynodioecy,

and an updated online database” by Susanne S. Renner [101(10):1588, 2014]

• “Phloem development: Current knowledge and future perspectives” by Jung-ok Heo, Pawel Roszak,

Kaori M. Furuta, and Ykä Helariutta [101(9):1393, 2014]

• “The role of homoploid hybridization in evolution: A century of studies synthesizing genetics and

ecology” by Sarah B. Yakimowski and Loren H. Rieseberg [101(8):1247, 2014]

• “The polyploidy revolution then…and now: Stebbins revisited” by Douglas E. Soltis, Clayton J.

Visger, and Pamela S. Soltis [101(7):1057, 2014]

• “Plant evolution at the interface of paleontology and developmental biology: An organism-

centered paradigm” by Gar W. Rothwell, Sarah E. Wyatt, and Alexandru M. F. Tomescu [101(6):899, 2014]

• “Is gene flow the most important evolutionary force in plants?” by Norman C. Ellstrand [101(5):757, 2014]

• “Repeated evolution of tricellular (and bicellular) pollen” by Joseph H. Williams, Mackenzie L.

Taylor, and Brian C. O’Meara [101(4):559, 2014]

• “The voice of American botanists: The founding and establishment of the American Journal of

Botany, ‘American botany,’ and the Great War (1906-1935)” by Vassiliki Betty Smocovitis [101(3):389, 2014]

• “The nature of serpentine endemism” by Brian L. Anacker [101(2):219, 2014]

• “The evolutionary-developmental origins of multicellularity” by Karl J. Niklas [101(1):6, 2014]

• “The American Journal of Botany: Into the Second Century of Publication” by Judy Jernstedt

[101(1):1, 2014]

These articles are also hosted at www.botany.org/ajb100, and the site also hosts other free content---

nearly 1000 articles from the history of the AJB, as written by the journal’s top 25 contributors! The AJB is

one of the few surviving plant science publications published by a non-profit scientific society. The journal,

and its authors, reviewers, editors, readers, and subscribers, are at the heart of the Botanical Society of

America, and the strength of this connection makes the AJB stand out from many other journals.

135

Plant Science Bulletin 60(3) 2014

Ray Evert

Ray Evert joined the BSA in 1955---nearly 60

years ago!---and served as the Society President in

1986. He also won the the Society’s most prestigious

award, the BSA Merit Award, in 1982. Ray went

on to publish 39 articles in the American Journal

of Botany, and he recently took time to discuss his

career and some of his key AJB research.

My first article published in AJB was “Some

aspects of cambial development in Pyrus communis”

in 1961. My principal research interest at the

time was the vascular cambium and seasonal

development of the secondary phloem in trees.

Katherine Esau was my major professor, and my

Ph.D. thesis (Phloem structure in Pyrus communis

and its seasonal changes. Univ. Calif. Publ. Bot.

1960.32, 127-194) was patterned after her similar

study on the grapevine.

Two articles (my latest) were published in AJB

in 1994 and dealt with vastly different topics

(“Ontogeny of the vascular bundles and contiguous

tissues in the maize leaf blade” by A.M. Bosabalidis,

R.F. Evert, and W.A. Russin; the other, “Development

and ultrastructure of the primary phloem in the shoot

of Ephedra viridis (Ephedraceae)” by R.A. Cresson

and R.F. Evert.

As indicated, my early research was on the

vascular cambium and seasonal development

of the secondary phloem in trees (eudicots and

conifers). With the advent of electron microscopy,

I began ultrastructural studies on the phloem of

woody and herbaceous eudicots, monocots, and

gymnosperms. This was followed by extensive

studies on the comparative ultrastructure of