P

LANT

S

CIENCE

Bulletin

SPRING 2015 Volume 61 Number 1

In This Issue..............

New Editor-in-Chief

Mackenzie Taylor discusses

plans for the PSB......p. 5

Show your true love for plants -

Join in the Celebration .....p. 13

Can your research qualify you for a BSA Award.....?

Thank-you to BSA members who

help build a robust endowment

fund!.....p. 2

From the Editor

Spring 2015 Volume 61 Number 1

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

Editorial Committee

Volume 61

Kathryn LeCroy

(2018)

Biological Sciences, Ecology and

Evolution

University of Pittsburgh

4249 Fifth Avenue

Pittsburgh, PA 15213

kalecroy@gmail.com

Lindsey K. Tuominen

(2016)

Warnell School of Forestry &

Natural Resources

The University of Georgia

Athens, GA 30605

lktuomin@uga.edu

Daniel K. Gladish

(2017)

Department of Botany &

The Conservatory

Miami University

Hamilton, OH 45011

gladisdk@muohio.edu

Carolyn M. Wetzel

(2015)

Biology Department

Division of Health and

Natural Sciences

Holyoke Community College

303 Homestead Ave

Holyoke, MA 01040

cwetzel@hcc.edu

Greetings! I am delighted to write to you for the first

time as Editor-in-Chief of the Plant Science Bulletin.

This year, 2015, marks the 60th anniversary of the PSB.

For more than half a century, the articles and editorials

in the PSB have documented the history of the Botani-

cal Society of America and chronicled the contempo-

rary concerns of practicing botanists. It is with great

pleasure that I step in as curator of this legacy.

It is my goal that, during my tenure, the PSB will be a

platform for lively discussions on the issues currently

facing us, as botanists. I hope that you will look to the

pages of this publication as a source for news, perspec-

tives, and inspiration, as well as for resources for teach-

ing and outreach. However, none of this will be possible

without your contributions. I encourage you to reflect

on the ideas and perspectives that you can bring to the

PSB and to let your voice be heard. You can read more

about my vision for the Plant Science Bulletin on page 5.

This is also a time of transition for the American Jour-

nal of Botany. Hear from Editor-in-Chief Pam Diggle on

page 8 and find a summary of new features rolling out

in 2015. I also want to draw your attention to a new

section of the PSB devoted to student news and per-

spectives. In its debut, this section features an interview

with 2014 Karling Award winner, Catherine Rushworth

(page 15).

Thank you to everyone on the BSA staff who has worked

to make my transition into this position as smooth as

possible, particularly Richard Hund, Amy McPher-

son, Beth Parada, and Johanne Stogran. These dedi-

cated people work tirelessly and skillfully behind the

scenes to produce a quality publication and have been

nothing but positive and patient while I have learned

the process of putting this publication together. I es-

pecially want to thank Marsh Sundberg for his ex-

ceptional work as PSB Editor-in-Chief over the last

15 years and for his help in showing me the ropes.

I look forward to guiding the Plant Science Bulletin

through the next five years and to reading your compel-

ling and insightful contributions.

1

Table of Contents

Society News

BSA Endowment Fund: The Fund that Keeps on Giving ..................................................2

BSA Endowment Fund Donors 2014 .................................................................................2

New Editor Mackenzie Taylor on the Future of the Plant Science Bulletin .......................5

Pamela Diggle, New Editor-in-Chief, Discusses the Future of the

American Journal of Botany ...............................................................................................8

BSA Science Education News and Notes

Raising the Next Generation of Botanists ........................................................................12

Fascination of Plants Day .................................................................................................12

Congratulations to Fall PlantingScience Star Project Winners! .......................................13

BSA Committees in Action

Public Policy News ...........................................................................................................14

Student Section

A Moment with Catherine Rushworth, Winner of the 2014 J. S. Karling Award ............15

Award Season Underway ..................................................................................................17

Announcements

New England Botanical Club 120th Anniversary Research Conference .........................18

Eagle Hill Institute Natural History Science Field Seminars ..........................................18

“Climate Change and the Future of Plant Life” Symposium Hosted by the

New England Wild Flower Society ..................................................................................18

The Oxford Plants 400 Project .........................................................................................19

Book Reviews

Bryological and Lichenological ......................................................................................20

Physiological ....................................................................................................................21

Systematics .......................................................................................................................23

Shaw Convention Centre - Edmonton

July 25 - 29, 2015

Abstracts and Registration Sites now open

www.botanyconference.org

2

Society News

BSA Endowment Fund:

The Fund that Keeps on Giving

The BSA’s Future is Secure Because

of Members Like You

By Joseph Armstrong, At-large

Director Development

A robust endowment is an essential component

of every nonprofit organization, and the case for a

strong endowment to ensure long-term financial

sustainability is vitally important to the BSA. As we

move forward in our mission,

Endowment Fund

contributions are critical to achieving the financial

flexibility necessary to continue supporting our

members with our many programs, publications,

awards, and education programs.

Only nine years ago, a small group of our long-

time members came together to establish this very

important fund by creating a Legacy Society. Their

foresight, generous donations, shared purpose,

and deep commitment to our mission set a very

powerful example—now, every year, the BSA

Legacy Society continues to grow in membership.

While members of our Legacy Society have

provided an important foundation for our

endowment, each year we encourage all of our

members to consider contributing to the fund so

that it may grow and sustain in perpetuity all that

we as a Society have built. Our Endowment Fund

is what allows us to plan for the future and secure

our mission.

If the BSA has assisted you during your botanical

career and/or the advancement of your science,

please consider contributing to our endowment.

Whether it is through publishing, sharing/

gathering research at meetings, receiving an award,

supporting your students, or importantly, having

fellowship with other botanists, we trust the BSA

has made more possible for you. Visit https://

donations.botany.org/endowment/ to make a gift.

We are grateful to each of our members who

now continue to provide yearly gifts toward the

endowment, and we would like to acknowledge

them and applaud the numerous first-time

contributors to the fund during 2014. It is through

your dedication to the vision and mission of the

BSA that we may thrive today and continue to

thrive in the future.

Thank you on behalf of every BSA member, and

our future members. For more information about

the Legacy Society, visit http://botany.org/legacy/.

To donate, please visit https://donations.botany.

org/LegacySociety/.

BSA Endowment Fund

Donors 2014

James Ackerman

Gregory Anderson

Annie Archambault

Joseph Armstrong

Tina Ayers

Nina Baghai-Riding

Amy Berkov

Lynn Bohs

Kyle Bolenbaugh

David Boose

Andrew Bowling

Winslow Briggs

Linda Broadhurst

M. Brooke Byerley

Diane Byers

Brenda Casper

Barbara Castro

Ronald Chaves

Gregory Cheplick

Lynn Clark

Wendy Clement

Edward Coe Jr.

Jim Cohen

Margaret Collinson

Joseph Colosi

Margaret Conover

Martha Cook

3

Plant Science Bulletin 61(1) 2015

Michele Correa

Suzanne Costanza

Nancy Cowden

Barbara Crandall-Stotler

William Crepet

Emily Crone

Wilson Crone

Quentin Cronk

Peter Curtis

Douglas Daly

John Danforth

Stephen Davis

Carol Dawson

Rebecca Dellinger-Johnston

Darleen Demason

Jennifer Dewoody

Stephen Dickey

Pamela Diggle

Alexa Dinicola

Andrew Doust

James Doyle

Jane Doyle

Michele Dudash

Bohdan Dziadyk

Shona Ellis

Norman Ellstrand

W Eshbaugh

Belen Estebanez Perez

Karen Fawley

Charles Fenster

Johannah Fine

Jack Fisher

Maura Flannery

Stephan Flint

Irwin Forseth

Ned Friedman

Alan Franck

Mark Gabel

Patrick Gallagher

Nancy Garwood

Ibrahim Gashua

Monica Geber

Patricia Gensel

David Gernandt

Lawrence Giles

Thomas Givnish

Doris Goldman

Carol Goodwillie

Morgan Gostel

Candice Groat

Yaffa Grossman

Benjamin Hall

Carolyn Hall

Gary Hannan

Sue Harley

Clare Hasenkampf

Christopher Haufler

Donna Hazelwood

Francoise Hennion

Ann Hirsch

Noel Holmgren

Patricia Holmgren

Kent Holsinger

Jodie Holt

Sara Hoot

James Horn

Harry (Jack) Horner

Shing-Fan Huang

David Inouye

Sarah Jacobs

Lawrence Janeway

Eugene Jercinovic

Judy Jernstedt

Kirsten Johnson

Cynthia Jones

Nisa Karimi

Elizabeth Kellogg

Colleen Kelly

Sharon Klavins

John Knox

Vanessa Koelling

Suzanne Koptur

Jamie Kostyun

Jean Kreizinger

Svetla Kukleva

Siro Kurita

Kitty Labounty

Rebecca Lamb

Roger Laushman

Julio Lazcano Lara

Elton Leme

Blanca Leon

Amy Litt

Stefan Little

Tatyana Livshultz

David Longstreth

Marilyn Loveless

Anne Lubbers

James Mahaffy

William Malcolm

Uromi Manage Goodale

Maria Mandujano

Greayer Mansfield-Jones

Karol Marhold

Amelia Mateo Jimenez

Mark Mayfield

Gloria McClure

Richard McCourt

Lucinda McDade

David McLaughlin

Nicholas McLetchie

Helen Michaels

Luke Moe

Brenda Molano-Flores

Arlee Montalvo

Jin Murata

Sandra Newell

Karl Niklas

Robert Noyd

Richard Nuss

Paulo Oliveira

Richard Olmstead

Barnabas Oyeyinka

V. Thomas Parker

Judith Parrish

Nuri Pierce

William Platt

Pamela Polloni

Elisa Porter

4

Plant Science Bulletin 61(1) 2015

R. Brandon Pratt

Relf Price

Robert Price

Leonard Pysh

Tom Ranker

Jennifer Read

Jennifer Richards

Victor Riemenschneider

Diane Robertson

Paulo Ruas

Francis Russell

William Saucier

Carl Schlichting

Andrew Schnabel

Al Schneider

Edward Schneider

Tanja Schuster

James Seago

Cynthia Sechrest

Joanne Sharpe

Leila Shultz

Judith Skog

Laurence Skog

Erik Smets

Allison Snow

Pamela Soltis

Victoria Sork

David Spooner

Alice Stanford

Peter Stevens

Dennis Stevenson

Johanne Stogran

Sharon Strauss

Andrew Stuart

Susan Studlar

Frank Suarez

Marshall Sundberg

Mackenzie Taylor

Thomas Taylor

William C. Taylor

Irene Terry

Nicholas Tippery

Leslie Towill

Tommy Ultan-Thomas

Caroline Umebese

Garland Upchurch

Imena Valdes

Luis Valenzuela-Estrada

P. Leszek Vincent

Naomi Volain

Don Waller

Tom Waters

James Watkins

Linda Watson

Anton Weber

Catherine Weiner

Jacob Weiner

Elisabeth Wheeler

Richard Whitkus

Norman Wickett

Alex Widmer

Charles Williams

Joseph Williams

Robert Wise

George Wittler

Martin Wojciechowski

Paul Wolf

Andrea Wolfe

Anne Worley

Atsushi Yabe

Jingbo Zhang

Wendy Zomlefer

5

Plant Science Bulletin 61(1) 2015

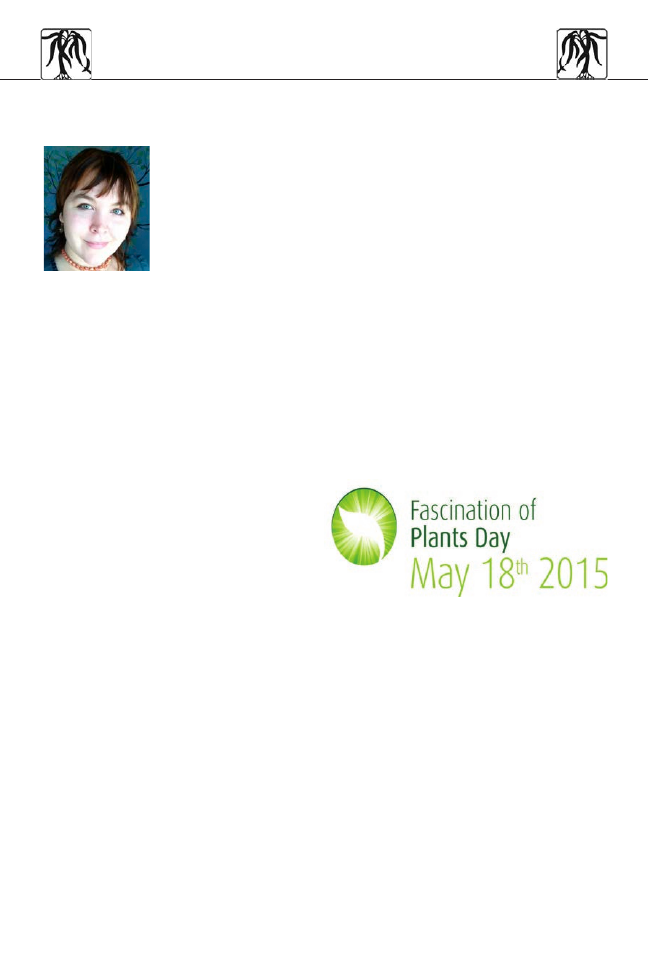

New Editor Mackenzie Taylor

on the future of the Plant

Science Bulletin

Mackenzie Taylor, assistant professor at Creighton

University, has been a long-time reader of the Plant

Science Bulletin, so when she accepted the position

as its new editor, she saw an opportunity to honor the

past 60 years of publication while moving the PSB

into a new era. Marian Chau of Lyon Arboretum/

University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa---and fellow former

BSA student representative along with Taylor---

spoke with Taylor about her vision for the next 5

years of the PSB.

Chau: What made you decide to pursue the

Editor-in-Chief position for PSB?

Taylor: I have loved reading the Plant Science

Bulletin since I first became a member of the

Botanical Society of America. When I first started

considering the possibility of becoming editor of

the PSB, I got very excited because I firmly believe

that the PSB is an invaluable resource for BSA

members and the entire botanical community. I

knew that Editor-in-Chief Marsh Sundberg had

been working very hard, in cooperation with the

BSA staff, to continually refresh the PSB and keep

it relevant, even as the way we obtain information

changes. The idea of being able to contribute

directly to the legacy of the Plant Science Bulletin

and to shape the future direction of this publication

is extremely attractive to me.

As a long-time reader of the PSB, what have

you always liked about the issues? What features

have you always wanted to see more of?

There are many things that I like about the Plant

Science Bulletin. The PSB is, for me, a way to stay

connected to the botanical community year-round.

I appreciate that this publication is truly centered

around BSA members, highlighting the successes,

concerns, and activities of the membership. I enjoy

reading about the contributions that members are

making in the realms of education, outreach, and

advocacy. These activities often don’t receive the

recognition that they deserve, even though they

are, in my opinion, as important as contributions to

scientific research. I think it is essential that the PSB

showcase and promote these endeavors.

I also enjoy the variety of topics that each issue

covers. A particular issue might include an article

with a historical focus, followed by an article

discussing strategies for teaching, accompanied by a

profile of an award-winning member. Ideally, there

is something for everyone in each issue. Further, in

many cases, the articles and notes published in the

PSB focus on successes, either for the society or for

individual members. I find these positive features

refreshing and inspiring.

Over the next five years, I would like to see

input from an increasing proportion of the BSA

membership. Members of the BSA come from a

variety of professional settings and from all possible

career stages. They have diverse interests, face a

variety of professional challenges, and bring unique

and valuable perspectives to the society and to the

field of botany. I want to make sure that those voices

are heard in the pages of the PSB. With that goal

in mind, we are asking the student membership

to contribute to a dedicated section in each issue

and the student representatives have taken on the

challenge of organizing this section. I also want

to encourage post-docs and other early-career

scientists, as well as botanists who work outside

of the traditional academic setting, to consider

submitting articles and essays.

In the coming issues, I hope to facilitate even

more discussion regarding issues of public policy

and science advocacy. In today’s academic and

political climate, it seems especially important

that BSA members be equipped with information

and strategies for promoting botany, and indeed

science, at local, national, and international levels.

Mackenzie Taylor - The new PSB editor.

6

Plant Science Bulletin 61(1) 2015

I know being a Student Representative on the

BSA Board was a career-changing experience for

me. What did you gain from your experience as

the first BSA Student Representative that you can

apply to your position as PSB Editor-in-Chief?

I think that my experiences as the student

representative will be extremely beneficial as I

take on the responsibility of the PSB. I learned a

great deal about the governance of the Botanical

Society of America and gained a much deeper

understanding of, and appreciation for, the BSA

mission. As the student representative, I had many

conversations about the challenges facing students,

in particular, but also other early-career scientists,

and I was exposed to a variety of perspectives that

I might not have come to understand otherwise. I

think that these experiences will help me move the

PSB forward, while honoring its history.

The PSB has been around for 60 years now.

How do you maintain the legacy of a publication

like this while also staying current, looking to the

future, and engaging younger readers?

I believe that the key to maintaining the legacy

of the Plant Science Bulletin is staying true to its

original mission. When the PSB was established,

the goal of the publication was to unify the

botanical community. The original editor Harry

J. Fuller envisioned the PSB as a forum for

discussions about important issues facing botanists

and as a place where people could share an array

of information, including strategies for coping with

the academic environment, resources for teaching

and scholarship, information about conservation

activities, and discussions about issues of academic

freedom. The need for these types of discussions

hasn’t changed.

Staying current first requires that the issues

presented and discussed in the PSB be relevant to

the membership. It is my hope that we can engage

younger readers and others who aren’t currently

reading the PSB by including articles and notes

that are of interest to those demographics. We

will also employ strategies for reaching and

engaging readers who access information

in new and different ways. For example, we

plan to make short items, including news and

announcements, available electronically in a

more timely manner than is possible with the

quarterly publication cycle and, ultimately,

upgrade the PSB website so that content from

the print publication is more directly accessible

in a digital format.

Do you think the way we talk (and write)

about the discipline of botany has changed in

recent times? Does this affect the type of PSB

submissions you would like to see?

I’ve spent quite a bit of time reading the

back issues of the PSB and the significant issues

that concern botanists are strikingly similar

throughout the last 60 years. In my opinion,

the majority of editorials and articles published

in the first five volumes of the PSB easily could

have been written in the last five years, although

there are several references to playing Bridge

that are less culturally relevant.

For example, the first issue of the PSB

includes an essay entitled The Challenge to

Botanists by Sydney S. Greenfield, chair of

the Education Committee. In this article, he

sets out the challenges facing botanists in

1955, including a decline and elimination

of botany from undergraduate curricula, an

underrepresentation of botanists in biology

departments and among general biology

educators, and a lack of appreciation for botany

by the general public. If you read the issues from

the 1970s and 1980s, the same general themes

continually pop up and we continue to struggle

with these issues today.

I want to see PSB submissions that are useful

to the BSA membership. I firmly believe that

the Plant Science Bulletin should reflect the

“Members of the BSA . . . bring

unique and valuable perspectives

to the society and to the field of

botany. I want to make sure that

those voices are heard in the pages

of the PSB.”

“

I firmly believe that the Plant

Science Bulletin should reflect

the concerns of the current

membership

and

provide

resources that will help its readers

be more successful teachers,

scholars, and citizens.”

7

Plant Science Bulletin 61(1) 2015

concerns of the current membership and provide

resources that will help its readers be more

successful teachers, scholars, and citizens.

How does someone, especially an early-career

botanist, benefit from submitting an article to

you?

The Plant Science Bulletin is an excellent venue

for anyone who wants to communicate information

that doesn’t fall into the traditional scientific

research article format. We are especially interested

in publishing articles and essays that focus on

education, public policy, outreach, professional

resources, and history. Any botanist, including

those early in his or her career, may have an interest

in these areas, be particularly involved in outreach

or advocacy activities, or have developed course

materials or resources that might not be quite

appropriate for publication in an education journal.

The Plant Science Bulletin provides an outlet for

those types of scholarly outputs that might not be

published otherwise. Moreover, articles published

in the PSB as “Feature Articles” undergo peer

review. This elevates the quality of articles published

in the PSB and benefits the author, as these articles

should be considered peer-reviewed publications in

CVs and dossiers.

Publishing in the Plant Science Bulletin is also

a great way for early-career botanists to network

with colleagues who have similar interests and to

get their names out into the botanical community.

Articles and essays in the PSB have the potential to

reach the entire BSA membership, as well as those

with a passing interest in the botanical sciences.

The PSB also publishes book reviews and this

section is one of our members’ favorite features.

I would encourage everyone, particularly early-

career scientists, to consider contributing to this

section. If you are interested in reading a particular

book, why not go the extra step and prepare a review

of that title? You will receive a complimentary

review copy of the book, have the opportunity to

contribute to the scientific community, and have a

published book review for your records.

What if someone has an idea for an article but

isn’t sure about the next step?

If you have an idea for an article or essay, the

easiest first step you can take is to email me at psb@

botany.org. I will be more than happy to discuss

your idea and we can strategize about preparing the

article for publication in the Plant Science Bulletin.

You can also find information about the types of

articles we publish and instructions for authors

at http://botany.org/PlantScienceBulletin/. If you

already have an article prepared, you can submit it

directly for review using the submit button found at

http://botany.org/PlantScienceBulletin/.

What can readers look forward to in 2015?

What is your ultimate vision for the PSB?

Readers can look forward to regular

contributions from BSA committees, particularly

the public policy and education committees, as well

as the student membership. This increased focus on

the activities of BSA committees and other groups

is intended to keep the membership aware of what

is happening within the society.

As I mentioned earlier, we are experimenting

with new ways to deliver PSB content to the

membership that will supplement, not replace,

the print version of the Plant Science Bulletin. In

particular, we are working toward having URLs

for individual articles so that they can be accessed

directly and publicized on social media platforms.

Readers should also expect to see a fresh look to the

print PSB starting in 2016.

My vision for the Plant Science Bulletin is for it

to be the voice of the Botanical Society of America.

The PSB should feature content that reflects the

varied interests of BSA members, be a dependable

source for resources and perspectives, and provide

a forum for lively discussion and constructive

debate. However, the composition of the PSB is

ultimately in the hands of the BSA membership.

The PSB depends on member submissions and it

is those contributions that our readers are eager

to read every quarter. I am looking forward to

receiving those submissions and guiding the Plant

Science Bulletin forward through the next five years.

8

Plant Science Bulletin 61(1) 2015

Pamela Diggle, New Editor-

in-Chief, Discusses the Future

of the American Journal of

Botany

Pamela Diggle recently stepped into the role of

Editor-in-Chief of the American Journal of Botany,

and she has started to implement some changes for

AJB in 2015 while maintaining the journal’s legacy.

Nic Tippery,

from the University of Wisconsin–

Whitewater, recently spoke with Diggle about her

vision for the journal.

Tippery: What inspired you to pursue the

Editor-in-Chief position for the AJB?

Diggle: Did you see my tweet? #Iamabotanist! I

am committed to research, teaching, learning, and

outreach about all things botany. The Botanical

Society of America and its flagship journal, the

American Journal of Botany, are central to all of

these activities, and the Editor-in-Chief position

provides an opportunity for me to support botany

and botanists.

What strengths do you think you can bring to

the position?

The Editor-in-Chief will need to understand

what areas of plant science research are growing,

what graduate students are interested in, what

people are teaching, and what societal issues are

relevant to research in plant science. My recent

experiences as a Program Officer at the National

Science Foundation and continuing service on

various NSF panels, and my leadership in two very

broad-based biology departments (Chair of one,

Associate Head of the other), provide me with a

profound appreciation of the depth and breadth of

science that should be encompassed within AJB. I

am also committed to exploring new opportunities

to remain abreast of developments in botanical

science. Attending scientific meetings of diverse

disciplines, and interacting with scientists who

attend them, will be an important activity that will

supply new ideas and focus.

The AJB just celebrated 100 years of

publication. How do you perceive the legacy of

the AJB?

AJB has a special role in the botanical sciences.

From its inception, AJB has been a forum for

scholarship from diverse areas of botanical research.

In this era of hyper-specialization, and organization

of academic departments and journals around

particular areas of research, AJB provides a venue

for publications that span levels of organization

ranging from molecules to ecosystems. Papers in

the American Journal of Botany are read by people

in the same field, but are also seen by readers from

diverse fields, with the potential to be incorporated

into new research programs, graduate discussion

groups, and graduate and undergraduate

coursework.

The spectacular series of Centennial Review

papers that began in 2014 perfectly embodies the

legacy of AJB (see www.amjbot.org/content/by/

section/AJB+Centennial+Review). To celebrate the

tremendous achievement of 101 years of influential

publication of the American Journal of Botany,

then Editor-in-Chief Judy Jernstedt invited leading

scientists to address long-standing questions in

botanical research. Each topic has a long history of

coverage in AJB, and the range of topics covered in

these reviews demonstrates perfectly the breadth

and impact of articles published in the journal.

They range from the very origins of multicellularity,

through phloem development and function, to

diverse aspects of evolutionary dynamics including

gene flow, hybridization, polyploidy, and many

others; these papers epitomize the high standards

that are the legacy of AJB: breadth of topics covered,

rigorous scholarship, innovative and insightful

analyses, and a view to emerging areas of interest.

The legacy of AJB also derives from the

dedication of the many people who work very hard

to ensure the quality of the journal, each and every

month. They include the professional editorial

staff, the Board of Associate Editors, the BSA

Director-at-Large for Publications, the Publications

Committee, the many, many reviewers, our authors,

and BSA members. The legacy of AJB is a legacy of

the commitment of the community that supports it.

Pam Diggle takes the reins of the AJB.

9

Plant Science Bulletin 61(1) 2015

What do you see as the main challenges to

publishing in 2015, and what strategies do

you think will benefit the AJB in the current

publishing environment? What challenges do you

anticipate the journal will face over the next ten

years? How are you addressing those challenges?

The primary challenge faced by AJB is the same

challenge faced by the publications of all scientific

societies: How will the Journal maintain relevance

in this rapidly evolving world of diverse outlets

for dissemination of science? As mechanisms for

distributing and accessing data and other types of

information become more diverse and immediate,

why will scientists need journals? Why should

authors and readers choose AJB?

As Editor-in-Chief, my job is to understand what

authors, subscribers, and society members want

from the journal. My most important first priority

has been to listen to and learn from that community.

I held a series of conference calls with small groups

of scientists––in collaboration with Sean Graham,

BSA Director-At-Large for Publications, and Amy

McPherson, Managing Editor of AJB––who have

very diverse research interests and are at different

career stages, for wide-ranging conversations about

publication in general and how we might enhance

the value and impact of the journal. The people we

spoke to valued rigorous, constructive, fair, and

timely review most highly out of all of the topics

discussed, and these will remain critical goals for

AJB as we move forward.

“Audience” is also widely considered to be an

important factor that scientists consider when

choosing a journal. Our participants valued the

broad range of readers that AJB brings, and it

is clear that enhancing our readership will be

a valuable asset in attracting new authors. AJB

currently serves authors and readers by publicizing

papers in multiple outlets: new papers are featured

on the society and journal websites, and promoted

via social media and press releases. Special Issues

and Special Papers also bring new authors and

readers to AJB. It will be important to continue to

develop exciting new ways to push our articles out

into the broader community of scholars.

As a result of our initial discussions with members

of the botanical community, I have already brought

some significant changes to the journal. Beginning

with the January issue, AJB now has a prominent

new “News and Views” section. In this section will

be a novel type of essay, “On the Nature of Things.”

These are short essays that concisely summarize

a new and exciting issue or research area, take

a new look at an established area, or explore

an idea or concept. I envision a single journal

page with a bit of background, a summary of

the current state of thought or data, and then a

brief explanation and thoughtful summary of the

unanswered questions or where the field might

be going. The most important element of these

essays is the forward-looking part. I hope readers

anticipate these essays every month to see what

their colleagues are thinking about--and that

they’ll want to share their own ideas. The first

article of this kind is from Ken Feeley (of Florida

International University) whose essay on the

pitfalls of predicting future species distribution

and the promise of new approaches just appeared

in the February issue of AJB (www.amjbot.org/

content/early/2015/02/03/ajb.1400545.full.

pdf+html)

“From its inception, AJB has

been a forum for scholarship

from diverse areas of botanical

research. In this era of hyper-

specialization, and organization

of academic departments and

journals around particular areas

of research, AJB provides a

venue for publications that span

levels of organization ranging

from molecules to ecosystems.”

AJB now also features a “Highlights” section

that summarizes selected articles in each issue.

These are intended to entice readers to want to

know more about the journal’s contents.

A second challenge to the future of society

publications like AJB is financial; AJB does not

have the deep pockets of a large publishing

company. Our operating budget comes largely

from library subscriptions, but library budgets

are shrinking and, as open access (for which

authors pay to publish via grants or their

personal funds) grows, librarians are loath to buy

what is available for free. The consequence is the

cost of publishing is shifting more and more to

authors. AJB has adopted multiple strategies to

shield our authors from this burden. Bill Dahl,

the Executive Director of the BSA, the BSA

Board of Directors, and the professional staff of

10

Plant Science Bulletin 61(1) 2015

the BSA and AJB monitor financial developments

within the publishing industry closely, and we are

in constant discussion about the financial security

of the journal. Meanwhile, make sure that your

libraries know how much you value AJB!

Do you have any suggestions for people who

might be thinking about submitting an article to

the AJB?

AJB aims to publish papers that make a significant

contribution to botanical sciences. Authors should

frame their papers so that the significance is

evident to the general (but well informed!) reader.

If in doubt, I encourage potential authors to contact

me for feedback.

How can BSA members contribute to

maintaining the AJB as a strong journal in our

field?

Send your best work and cite papers in AJB!

Volunteer to review manuscripts or to serve on the

publications committee of the BSA. Make sure that

your library subscribes to AJB. Participate in my

ongoing discussion about how we can enhance the

value and impact of the journal.

What is your ultimate vision for the AJB?

The AJB has changed dramatically over the past

century of publication and I will collaborate with

all of you to ensure that it continues to evolve in

exciting new ways. At the same time, the foundation

of the journal should remain unchanged. The

American Journal of Botany is one of the premier

outlets for all aspects of botanical discovery and

knowledge, with papers that stand the test of time,

and continue to shape the intellectual horizons of

our discipline. I look forward to leading AJB over

the coming five years, and I especially look forward

to reading your very best research papers there.

The American Journal of Botany Welcomes a New

Editor-in-Chief and Launches New Features

The January issue of the American Journal of Botany begins the tenure of new Editor-in-Chief Dr.

Pamela Diggle and outlines new features rolling out in 2015 as well as other upcoming developments.

Beginning in January, AJB features a new front section titled “News and Views,” which will

include editorials, commentaries, letters to the editor, and a new article type called “On the Nature

of Things” (OTNOT for short). These brief, open access essays—a hybrid of a blog-post and a mini-

review—are meant to provide succinct and timely insights into multiple aspects of plant science.

They will summarize the current state of thought, technology, or understanding, with the bulk

of the essay devoted to looking forward to what might be on the horizon for this issue, question,

or area of research. The feature debuted in the February issue with “Moving forward with species

distributions,” by Kenneth Feeley at http://www.amjbot.org/content/102/2/171.full, and has

continued with “Parasitism disruption a likely consequence of belowground war waged by exotic

plant invader” by Chris Martine and Alison Hale in the March issue at http://www.amjbot.org/

content/early/2015/03/02/ajb.1500025.full.pdf+html.

In addition to this new article type, AJB now includes a “Highlights” page at the beginning of each

issue. The Highlights point readers quickly to selected articles of interest. Visit http://www.amjbot.

org/content/102/1/1.full for a sample of this feature that debuted in January.

For more information on these features and more, see Dr. Diggle’s Editorial from January at http://

www.amjbot.org/content/102/1/3.full.l

In addition, AJB will focus on two special issues to be published later in 2015 and early 2016:

“Evolutionary insights from studies of geographic variation: Establishing a baseline and looking

to the future” and “The Ecology and Evolution of Pollen Performance.” More information will be

forthcoming—stay tuned!

11

Plant Science Bulletin 61(1) 2015

12

BSA Science Education

News and Notes

What first sparked your interest in science, and

in plants? Were you always science-minded, or

did you ever have to choose to pursue science over

competing fields of interest? Did you know from an

early age that botany would be a lifelong interest?

Or did you fall into studying plants later in your

science career, perhaps after meeting a botanist or

botany teacher who inspired you, joining an exciting

research project or coming across a particularly

intriguing plant? What fascinated you enough to

shift your research interests toward botany?

The mission of the BSA is to promote botany,

and inspiring interest in plants is a key part of

that mission. As Education Director, I’m keenly

interested in understanding when and how that

decision comes about, when children or adults

become fascinated with the plant world enough to

choose to make botany their life’s work.

The challenges of the 21st century ––climate

change, population increases, energy needs,

shrinking biodiversity––require a thriving

community of botanists who understand and

advocate for the plant world. Who knows what

contributions future colleagues will bring to the

field?

Inspiring the great thinkers of the next

generation and turning the interest of the science-

minded toward plant biology can be a challenge

when science, and especially plant science, is too

often such a small part of primary and secondary

education. The chance to experience science as a

process of discovery, and not just a set of formulas

and facts to memorize, can be instrumental.

Learning about plants from enthusiastic

professionals who are excited to share their life-

work can be much more impactful than learning

about plants from zoologists who see plants as a

backdrop for animal interactions, or from out-of-

field science teachers with no botany training and

who themselves have never had the opportunity to

learn how exciting plants can be.

So it is up to us, who find plants utterly

fascinating, to share that interest and excitement

with the next generation. And, because so many

young scientists make decisions about whether

they will be scientists at a young age, we need to be

sharing this interest and excitement not just with

our graduate students, or undergraduates, but with

secondary students and even primary students.

As Wandersee and Clary (2006) noted, “The

presence of a plant mentor earlier in one’s life

(someone who helped the mentee observe, plant,

grow, and tend living plants) is a key predictor

of that person’s awareness, appreciation, and

understanding of plants throughout the lifespan.”

Please consider reaching out, even in a small way,

to make a lasting impact.

Fascination of Plants Day

One perfect opportunity to share your fascination

with plants is through the upcoming Fascination of

Plants Day (FoPD) on May 18, 2015.

“FoPD is an internationally coordinated activity

designed to sow constantly germinating seeds

in the collective mind of the World Public to

appreciate and understand that plant science is

ofcritical significance to the social, environmental

and economic landscape now and into the future.”

Join other BSA members from around the world

in hosting a plant walk in your community on

May 18 and share your group’s discoveries with a

worldwide audience. University classes may be out,

but it is a perfect time to make a connection with

a local primary or secondary school, park, garden,

nature center, or museum.

Learn more about open events, get ideas for

By Catrina Adams,

Education Director

Raising the next generation

of botanists

13

Plant Science Bulletin 61(1) 2015

planning and sharing your own local events, and see

what initiatives are planned nationally (blog.aspb.

org/fascination-of-plants-day) or internationally

(www.plantday.org).

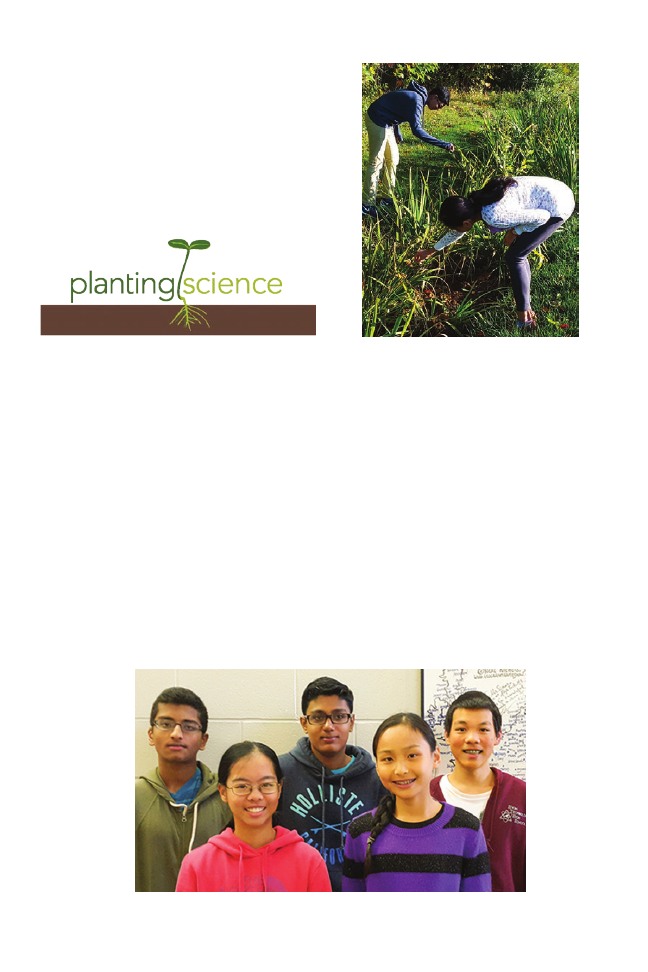

Congratulations To Fall

PlantingScience Star Project

Winners!

Through PlantingScience.org, the BSA promotes

plant biology and authentic science research for

students in middle and high schools around the

United States and world.

Each fall and spring, the most exemplary projects

are recognized in our Star Project Gallery. The fall

sessions’ winners included “The Bio Bunch” from

High Technology High School, who developed a

sophisticated proposal to determine the optimal

natural conditions for iris seed germination. The

team worked closely with their scientist mentor

Andrew Schnabel to generate ideas for a testable

question, craft a research prediction and research

design from their question, and prepare a full

proposal. In the process they learned a lot about

what it means to propose authentic research, and are

excited about conducting their planned research.

The Bio Bunch will carry out their ambitious

research proposal this spring session with their

mentor’s guidance. You can follow along with the

team’s progress at: http://tinyurl.com/biobunch.

All Spring projects are available to view at

plantingscience.org, using the “Research” tab.

If you would like to be a PlantingScience mentor

and help student teams discover the joy of scientific

discovery and become fascinated with plants, we

are now recruiting mentors for the fall session (mid

September – mid October). Register any time at

plantingscience.org/newmentor.

Anne and Arvind of PlantingScience star

project winning team “The Bio Bunch” collect

iris seeds for their experiment on optimal

conditions for seed germination.

PlantingScience star project winning team “The Bio Bunch” tackle iris seed

germination research project.

14

The start of 2015 has ushered in a major

change in the composition of Congress. Results

of the 2014 midterm elections mean that majority

turnover has taken place in the U.S. Senate and the

retirement and/or defeat of several Congressional

Representatives has meant that important

Congressional committees in the house are also

welcoming new faces. One change of particular

interest to scientists is that Senator John Thune (R-

SD) will be the new chair of the Commerce, Science,

and Transportation Committee (visit this link to

read more about specific committee changes: http://

www.aibs.org/public-policy-reports/2014_12_29.

html#034840). Federal funding for basic research

will be sure to face strong rhetoric in the 114th

Congress. The Public Policy Committee works to

provide you with the information you need to be

aware of including important votes, impending

policy changes, and communication networks

necessary to let your voice be heard. We need your

help to engage with politicians and other societies,

and advocate on behalf of botany!

How you can help:

Become involved with the American Institute for

Biological Sciences (AIBS) through their Legislative

Action Center (http://policy.aibs.org/) and sign

BSA COMMITTEES IN ACTION

up for public policy alerts every 2 weeks at http://

www.aibs.org/public-policy-reports/. Look out for

a survey from the Public Policy Committee with

questions regarding your specific policy interests.

We want to make sure we disseminate the policy

news that is relevant to our membership and the

only way we can do this is if we hear from you.

What we would like to do in the

future:

• Encourage proactive, rather than reactive,

policy involvement

• Help BSA members influence policy at

multiple levels (from local to national)

• Expand our interactions with other societies,

including a new collaboration with the ASPT

Environmental Policy Committee

• Offer AIBS Public Policy Workshops at future

meetings, including Botany 2015

Most importantly, we would like to develop a

charge to grow toward and in that regard, we’re

interested in what it is that you’d like to see from

the Public Policy Committee.

Upcoming policy events:

• May 13–14, 2015: Congressional Visits Day

hosted by the Biological and Ecological

Science Coalition. The BSA will sponsor two

awards in support of travel and lodging for

this event. The BSA has participated since

2012. The AIBS also sponsors an annual

award in support of travel and participation in

the CVD, which you can learn more about at

http://www.aibs.org/public-policy/eppla.html.

• Quarterly policy reports in the Plant Science

Bulletin.

• Upcoming BSA Member survey for Public

Policy Engagement. Please watch for this

survey in your email inbox! You can help guide

the future of the BSA Public Policy Committee

so that we can serve you better.

Public Policy News

by Marian Chau, and Morgan Gostel

Public Policy Committee Co-Chairs

BSA Public Policy Committee Overview

Since the formation of the Public Policy Committee in 2011, we have:

• Awarded six Public Policy Awards (2013 - 2015). We have already funded travel for six BSA student

and early career members to Washington, D.C.

• Partner with other societies, including the AIBS, ASPB, BESC, and ESA, in support of policy initiatives

for botany and federal funding of research.

• Author sign-on letters to Congress in support of sustained funding, in response to sequestration, and

in support of science policy efforts.

15

STUDENT SECTION

Beginning with this issue of the Plant Science

Bulletin, the student representatives to the

Botanical Society of America Executive Committee

will organize and contribute content for a

dedicated student section. It is our hope that these

articles will allow for more connectivity within the

student community of BSA, but it will also keep all

members informed on issues important to students

and the general news within the society.

In the future, we’d like to include short articles

about new methods and techniques, new

and interesting student-written publications,

iniormation about the annual meeting, and

interviews with noteworthy students.

If you have any ideas or suggestions on content

for future issues, we’d love to hear about them! Feel

free to contact Jon Giddens (gidd8708@gmail.

com) and Angela McDonnell (angela.mcdonnell@

okstate.edu), the current student representatives,

any time with your ideas. Alternatively, you can

connect with us on our Facebook group page by

searching for Students of the Botanical Society of

America.

A Moment with Catherine

Rushworth, winner of the 2014

J. S. Karling Award

Jon and Angela catch up with the fantastic Ms.

Catherine Rushworth of Duke University, who was

awarded the 2014 J. S. Karling Award for her top-

rated proposal titled “Insights into the origin and

persistence of apomixis in the Boechera holboellii

species complex.” Below, Catherine discusses her

thoughts on the BSA, her research, and how she stays

inspired.

Jon & Angela: When and why did you join

BSA?

Catherine Rushworth: I joined BSA at the

beginning of my grad school career. In my area of

research, most researchers are more stimulated by

the questions they’re asking than the organisms

they work with. I’m really a bit more organismal

in focus—my questions are motivated by the

peculiarities of a focal plant group. I love plants,

and I wanted to be part of an organization in which

the members love plants as much as I do!

What is your favorite thing about BSA?

My favorite thing about BSA is the enthusiasm its

members have for plants. At the conference in Boise

last year, it was so nice to meet other researchers

and enjoy an instant connection with them. Even if

their research was very distant from mine, we could

share excitement about the plants.

What is your research about?

I study the evolutionary factors maintaining

apomixis and sexual reproduction in populations

of the mustard Boechera. Apomicts are nearly

always polyploid and the result of hybridization,

but Boechera apomicts can be polyploid or diploid.

I focus on the diploid apomicts in order to eliminate

one confounding variable. I’m especially interested

in how sexual and asexual Boechera coexist in

populations. We know very little about how sexual

Catherine Rushworth

by Angela McDonnell and Jon Giddens,

Student Representatives

A Word from the Student

Representatives

16

Plant Science Bulletin 61(1) 2015

and asexual reproduction are maintained at the

population level in nature, and I’m lucky enough to

have a great study system to address these questions

in the field.

What has been the most challenging part of

your research?

I love doing fieldwork, but it can be really difficult.

Our lab spends 2-3 months every year living in

an RV park in rural Idaho. Working outdoors is

fantastic, but it’s hard to maintain forward progress

on your dissertation when you’re isolated for that

long with only a couple other scientists and a bad

internet connection! And, statistics is hard.

What has been the most rewarding part of

your research?

The most rewarding part is putting it all together.

I’m nearing the end of my dissertation and all my

experiments are nearly done. I’m learning how to

analyze my data properly and writing it up, and

amazingly enough, there are some answers to my

questions!

How has winning the J.S. Karling award

affected you and your research?

The J.S. Karling award has affected me in a couple

of different ways. First, monetarily, of course! It

enabled me to do an extra experiment this year that

I otherwise couldn’t have paid for, and I’m really

excited about the results. Second, I’m thinking

about postdoc projects, and having my face on a

giant screen definitely helped facilitate networking

with potential collaborators at the Boise meeting!

What advice do you wish someone would have

given you about graduate school?

There are too many things to list! But I wish

someone had sat me down on my first day of

grad school and said: “You are now a scientist.

Everything you do from here on out is your career,

so take it seriously and don’t discount yourself or

your abilities. You will meet a lot of smart people.

Don’t be intimidated by them, don’t be shy, and

don’t compare yourself to them; those things won’t

help you but will add stress to your life. This is

school, and you’re here to learn, so be prepared to

feel stupid a lot. Ask as many questions as it takes

until you figure a new concept out. And never

forget that you’re doing something you love!”

What do you do to de-stress?

I try to take tiny breaks, even 30 seconds,

throughout the day whenever I need to mentally

shift gears. They’re kind of like little palate cleansers

between courses of a fancy dinner; it helps me

switch to a new topic and keep going. If I’m really

stressed, and I can afford to take a big break, closing

the computer for a bit and spending time with my

husband and our cat always helps. And going for

walks! Getting outside is important.

What are you reading right now that’s

inspiring?

Right now I’m not really reading anything

but papers, but recently I started listening to this

podcast called Meet the Composer. (www.wqxr.

org/#!/programs/meet-composer/) I’ve been struck

by the similarities of the creative process that both

composers and scientists go through. I love hearing

how composers conceive of new pieces and mesh

styles of music, and the own unique ways in which

they put them down on paper, and how they create

pieces for certain musical groups (quartets or

whatever) based on those musicians’ specific skills.

There is no right or wrong way to think and create,

and I find that very inspiring. Maybe we could start

encouraging a bit more diversity in this area in

science.

What are your future aspirations?

I have an “unconventional” background (i.e., I

didn’t major in Biology in undergrad) so I never

thought I’d be faculty member material. But I’ve

come to find that I love research, I love teaching,

Cathy’s research focuses on hybrid apomicts in the

genus Boechera. An example of one is shown here,

likely involving parental species B. sparsiflora and B.

retrofracta.

17

Plant Science Bulletin 61(1) 2015

I love taking on leadership roles and mentoring,

and I kind of like writing. So it seems like academia

would be a good fit for me, after all. After my

upcoming postdoc at UC Berkeley, I’m going for it!

Anything else you’d like to include?

Thanks for this opportunity! And thank you,

BSA!

Award Season Underway

Although the year is just beginning, it is

important to keep in mind that the award season

is open!

The J. S. Karling Award is one of many

awards made by the society to graduate student

members in support of their research. This award

is named for Dr. John Karling (1897-1995) who

was an internationally renowned authority in

mycology (fungi) from Austin, Texas. In 1924

he received his Ph.D. from Columbia University.

Following graduation, Dr. Karling had a long and

distinguished career at Purdue University where

he served as the Director of the Department of

Biological Sciences and was also Purdue’s first

John Wright Distinguished Professor of Biological

Sciences. After retirement, he was named Fellow of

the Indiana Academy of Sciences and co-founder

of both the Mycological Society of America and the

American Institute of Biological Sciences.

The J. S. Karling Award is awarded to the top-

ranked proposal that is submitted for consideration

for a Graduate Student Research Award. The

purpose of the Graduate Student Research Awards

is to support and promote graduate research in the

botanical sciences. In response to student feedback

in recent years, the number of these Awards given

by the society has greatly increased from just ten

awards in 2004 to twenty awards in 2014.

The BSA also awards up to seven Undergraduate

Student Research Awards to fund quality research

performed by undergraduate students.

The solicitation for the 2015 Graduate and

Undergraduate Student Research Awards can

be found on the BSA website under the “awards”

subheading (http://botany.org/awards_grants/

detail/bsagsra.php;

http://botany.org/awards_

grants/detail/bsaUNDERgsra.php). The deadline

for these awards is March 15. Be sure to start

writing your proposal early and have it reviewed

by your peers and your PI well before you intend

on submitting it. And, if you’re not a student and

you’re reading this, please remind the students you

know to apply! Good luck!

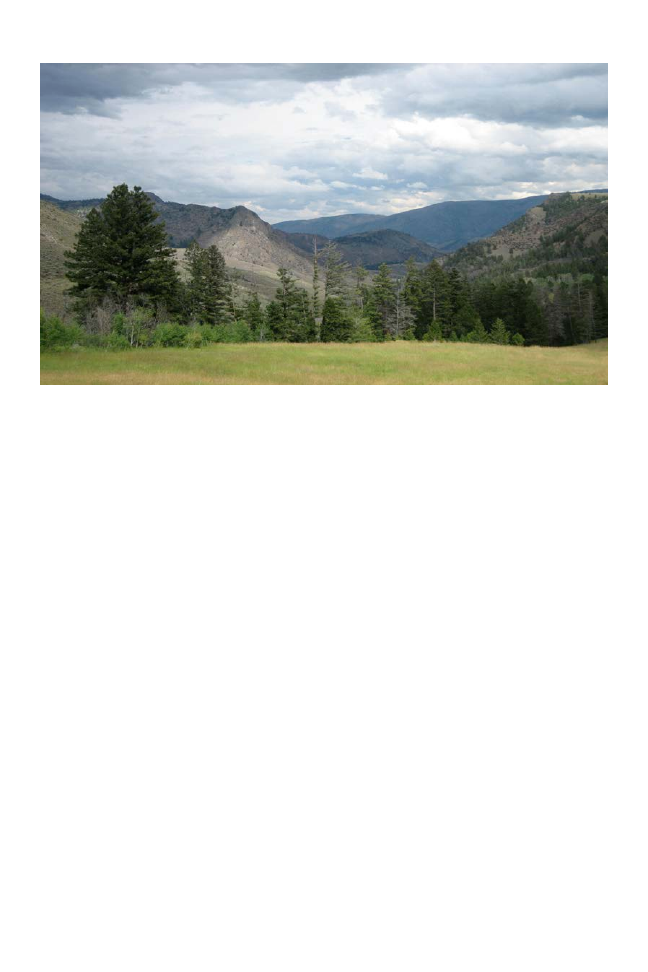

The Mitchell-Olds lab conducts field work in the Rocky Mountains of central Idaho. Shown here is the view

from one of their experimental gardens.

18

ANNOUNCEMENTS

New England Botanical Club

120th Anniversary Research

Conference

The New England Botanical Club is preparing to

celebrate its 120th anniversary by hosting a major

botanical research conference June 5-7, 2015, at

Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts.

This conference will bring together members of

the many botanical clubs and organizations that are

active in northeastern North America, as well as

students, academic researchers, naturalists, citizen

scientists and professional botanists. The keynote

speaker is Dr. Pamela Diggle, Editor-in-Chief of the

American Journal of Botany and Past President, the

Botanical Society of America.

We invite you to contribute to the conference by

presenting a talk or poster on your activities. There

will also be display space in which you can highlight

your organization, your latest botanical discoveries,

and new initiatives you are pursuing. On Sunday,

June 7, we will host a “working breakfast” in which

officers of clubs and societies can gather and

strategize about ways to make botany relevant to

an expanded audience. A botanical foray of Smith

College’s MacLeish Field Station will follow.

We encourage you to submit your full conference

paper for publication in our peer-reviewed journal,

Rhodora. All accepted abstracts will be published

as well.

This conference, including all meals and a

reception, is free. A full conference program

and online registration are available at NEBC

Conference.

Space is limited; register and submit an

abstract now! The final deadline for registration is

April 1, 2015. Please visit

http://www.rhodora.org/

conference2015/

for more information or direct

questions and comments to conference@rhodora.

org.

Eagle Hill Institute Natural

History Science Field Seminars

Eagle Hill Institute, located on the eastern

coast of Maine, will host seminars and workshops

focusing on natural history during Summer 2015.

These workshops are in support of field biologists,

researchers, field naturalists, faculty members,

students, and artists with interests in the natural

history sciences.

Courses include Trees and Shrubs of Northeastern

North America: Identification and Ecology; Plant

Identification and Herbarium Techniques; Mosses:

Structure, Ecology, and Identification; Introduction

to Maine Seaweeds: Identification, Ecology,

and Ethnobotany; Lichens and Lichen Ecology;

Grasses of Northeastern North America: Practical

Identification for Field Biologists; and Taxonomy

and Biology of Ferns and Lycophytes, among many

others.

A full list of 2015 seminars and workshops, as

well as registration information, can be found

at

http://www.eaglehill.us/programs/nhs/nhs-

calendar.shtm.

“Climate Change and the

Future of Plant Life” Symposium

hosted by the New England

Wild Flower Society

Plants are the foundation of global ecosystems,

creating the habitats that nurture all other living

beings. How will plants respond to the predicted

changes in temperature and precipitation from a

warming climate?

At this symposium, hosted by New England

Wild Flower Society, five noted botanists and

ecologists will discuss new findings and current

research on the state of New England’s plants;

the historical patterns and current evidence of

climate-induced adaptation, migration, and loss;

and strategies for conserving and managing plant

species and natural communities in the face of

climate change. Speakers include Dr. Paul Smith,

newly appointed Secretary General, Botanic

Gardens Conservation International; Dr. Elizabeth

Farnsworth, Senior Research Ecologist, New

England Wild Flower Society; Dr. David R. Foster,

19

Plant Science Bulletin 61(1) 2015

Director of the Harvard Forest, Harvard University;

and Dr. Dov F. Sax, Associate Professor of Ecology

and Evolutionary Biology at Brown University

and Deputy Director (Teaching) of the Institute at

Brown for Environment and Society.

The “Climate Change and the Future of Plant Life”

symposium will be held Thursday, March 26 from

9:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. at the Microsoft New England

R&D Center, 1 Memorial Drive, Cambridge, MA.

For more information about the symposium and to

register, go to

http://www.newenglandwild.org/sym

or contact Lana Reed, New England Wild Flower

Society Public Programs Coordinator, at lreed@

newenglandwild.org, 508-877-7630, ext. 330.

The Oxford Plants 400 Project

The University of Oxford will mark 400 years of

botanical research and teaching on July 25, 2021.

In celebration of this upcoming anniversary, the

University of Oxford Botanic Garden and Harcourt

Arboretum, together with the Oxford University

Herbaria and the Department of Plant Sciences,

has launched the Oxford Plants 400 project. This

project will highlight 400 plants of scientific and

cultural significance, with one plant profiled each

week. Each profile includes images from Oxford

University’s living and preserved collections. Check

out these plants at http://herbaria.plants.ox.ac.uk/

bol/plants400 and at @plants400 on Twitter.

From the

PSB Archives

60 years ago:

The first issue of the Plant Science Bulletin is published under editor

Harry J. Fuller. The editorial board consists of George S. Avery, Harlan P.

Banks, Harriet Creighton, Sydney S. Greenfield, and Paul B. Sears.

The Darbaker Prize in Phycology, presented for meritorious work in the

study of microscopic algae, is established.

50 years ago: The bylaws for the new Historical Section, created at the 1964 Council

Business Meeting, are published.

Stanwyn G. Shetler of the Smithsonian describes a visit to the Komarov

Botanical Institute in Leningrad prior to the opening of the Tenth

International Botanical Congress in Edinburgh.

25 years ago: New PSB editor Meredith Lane asks for “assistance in making the

PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN an active and interactive means of

communication within the Society” (a sentiment the current new editor

echoes).

In Memoriam notices are published for Ethel C. Belk and Louis Otho

Williams.

20

Book Reviews

Bryological and Lichenological

Flore des Bryophytes du Quebec-Labrador. Volume 1: Anthocerotes et Hepatiques. ..... 20

Physiological

Photosynthesis in Bryophytes and Early Land Plants ......................................................21

Systematics

Trees of Eastern North America .......................................................................................23

The Olmsted Parks of Louisville: a Botanical Field Guide ..............................................24

HAWS: A Guide to Hawthorns of the Southeastern United States ..................................25

The Genus Erythronium ...................................................................................................26

Plant Systematics: The Origin, Interpretation, and Ordering of Plant Biodiversity

(Regnum Vegetabile 156) .................................................................................................27

Bryological and Lichenological

Flore des Bryophytes du Québec-

Labrador. Volume 1: Anthocerotes

et Hepatiques

Jean Faubert

2012. ISBN-13: 978-2-9813260-0-3 (vol. 1)

Hardcover, C$80.00. 356 pp.

Société Québécoise de Bryologie, Saint-

Valérien, Québec, Canada

This is the first volume of a three-volume set

covering the non-vascular plants of Québec

and Labrador. The other two volumes, also by

Jean Faubert, deal exclusively with mosses (the

series was just completed in 2014). This volume

covers the remaining two lineages of bryophytes:

the liverworts and hornworts. It provides keys,

descriptions, habitat information, distribution

maps, and helpful hints to aid in identification for

all taxa present in Québec and Labrador; it also

includes several species that are not yet reported

from but are likely to occur in the area. In addition,

each genus is depicted by at least one illustration.

As pointed out in the preface, this work represents

the first since 1935 dealing exclusively with the

region, and the first-ever bryophyte flora exclusively

for Québec. Though in no way surpassing Rudolph

Schuster’s Hepaticae and Anthocerotae of North

America in its thoroughness and usefulness to

professional and ardent amateur bryologists, this

work represents a much more affordable, accessible,

and practical work for amateur bryologists. In

addition, the literature on liverworts and hornworts

is generally scattered and inaccessible. Therefore,

this book potentially represents an important

resource for anyone in eastern or boreal North

America.

An introductory section by the author describes

the layout of the rest of the work including how

to interpret generic descriptions and maps.

Information is provided on how to appropriately

collect and dissect bryological specimens as

well as on the biology of bryophytes, including

the obligatory description of the alternation

of generations life cycle. One section of this

introduction includes a list of ways in which

bryophytes differ from vascular plants and includes

a factually tenuous statement that bryophytes are

“resistant to the pressures of natural selection” (p. 6).

The keys in this work are nothing special and use

qualitative characters typically used in works on

hepatics (thallose vs. leafy, incubous vs. succubous

leaves, etc.). Hornworts are covered first, followed

by thallose liverworts, and finally leafy liverworts.

For each genus, an effort is made to allow the user to

key a specimen down to the lowest taxonomic level

possible. For example, in most floras Marchantia

polymorpha would be keyable only to species with

perhaps a note on its morphological variability.

Here, the user is able to key M. polymorpha to

one of the three subspecies found in Québec. An

additional nice aspect of the treatment is that

Faubert takes into consideration recent evidence

from molecular phylogenetic studies. For example,

eastern North American Conocephalum was once

all placed in the circumboreal C. conicum. However,

Faubert correctly ascribes material in Québec to

the recently described C. salebrosum. An effort is

also made to tackle difficult taxa such as Riccia,

Lophoziaceae, and Scapania, while at the same time

21

Plant Science Bulletin 61(1) 2015

cautioning the user that fertile material is usually

needed to confirm the identification.

As mentioned above, each species or subspecific

taxon is illustrated and a description and

distribution map are provided. Aside from the keys,

which are all typical ones that would be found in

a liverwort and hornwort flora, individual species

accounts are the most important aspect of a flora.

Unfortunately, this is the area where this book most

falls short. Three types of illustrations are used in

this work. First are typical line drawings. These

images are fine and make an effort to illustrate

diagnostic features such as the number of cells

per gemmae and trigones, although some species

might benefit from an additional illustration or two

for each species, especially for the hornworts where

spore characters are needed for identification but

no spores are depicted in this work. The second

type of illustration is an in situ depiction of the

plant. This is certainly useful in the field, but often

not as useful in the laboratory when plants, even

when rehydrated, may not look very similar to

these photographs. The large size (8.5 × 11 inches)

and dense glossy paper used in this book preclude

it from being taken in the field, and the immediate

utility of these illustrations is somewhat lost unless

the collector also takes photographs in the field.

The third type of illustration is a three-dimensional

rendering of plants solely for “aesthetic reasons to

show the beauty of bryophytes.” These illustrations

often look more comical than anything else (shoots

are often depicted on wood or granitic pedestals)

and do not serve any practical purpose. The

depictions of the plants in situ do so much more

to show the beauty of bryophytes. These three-

dimensional renderings would be much better

if they had been replaced by images taken of the

plants under a microscope as these images would

then have the potential to be both beautiful and

useful. One final issue with the treatment is that the

place of publication is listed for each species. This

is much better reserved for a monograph and just

wastes space here. One beneficial aspect of these

descriptions is that a bibliography of additional

resources is provided should one want to learn

more about a particular genus or confirm their

identification using another key.

The book concludes with an appendix of common

names in both French and English, although in some

cases the common names seem more complex and

harder to learn than the scientific names. Finally,

a glossary to bryological terms is provided. While

generally a good thing, this glossary falls short in

that it contains terms useful to the identification of

liverworts and hornworts but also contains moss-

specific terminology, which adds space and only

makes it more difficult for the user to find a specific

term.

Overall, this work represents a successful attempt

to provide a flora of Québec and is one of a handful

of accessible works on liverworts and hornworts of

eastern North America, especially as many of the

works are now out of print and expensive. However,

solely because the book is written in French, its

wider utility to those outside of Québec is limited

despite the fact that nearly all species may be found

in neighboring parts of Canada as well as the

northeastern United States. This book is therefore

recommended for those who can understand

French; those looking for illustrations would be

better served searching on used book websites or

should refer to Mary Lincoln’s

Liverworts of New

England: A Guide for the Amateur Naturalist (New

York Botanical Garden Press).

–Jeff Rose, Department of Botany, University of

Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, USA

Physiological

Photosynthesis in Bryophytes and

Early Land Plants

Advances in Photosynthesis and Respira-

tion, Volume 37

David T. Hanson and Steven K. Rice (eds.)

2014. ISBN-13: 978-94-007-6987-8

eBook, US$219.00; Hardcover, US$279.00.

342 pp.

Springer Science+Business Media, Dor-

drecht, The Netherlands

The Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration

series continues to grow with the addition of

Photosynthesis in Bryophytes and Early Land

Plants, the 37th volume in the series. Bryophytes

are fascinating organisms, in and of themselves,

that are also uniquely well suited for the study of

evolution and photosynthesis. Bryophytes contain

chloroplasts and a photosynthetic machinery

quite similar to their tracheophyte kin. However,

as they lack vasculature, a cuticle, stomata, and

aerenchyma tissues, photosynthesis in bryophytes

is very different indeed. In some respects, bryophyte

22

Plant Science Bulletin 61(1) 2015

photosynthetic mechanisms are similar to those

in tracheophytes. In others, there are significant

differences. Those similarities and differences,

along with recent advances in the field, underlie the

need for this timely, full-volume treatment of the

subject.

The volume is logically arranged. An introductory

chapter by the co-editors titled, appropriately, “What

Can We Learn from Bryophyte Photosynthesis?”

lays out the basic questions to be addressed in the

body of the book. The first set of chapters (Chapters

2–4) takes a three-phase evolutionary approach

by addressing the algal to bryophyte evolutionary

transition (Chapter 2), adaptations of early

bryophytes to the terrestrial environment (Chapter