IN THIS ISSUE...

PLANTS Grant Recipients and Mentors Gather at Botany 2015!

FALL 2016 VOLUME 62 NUMBER 3

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

A PUBLICATION OF THE BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA

Botany in Action Volunteers ready to go!

How BSA Can Influence Sci-

ence Education Reform...p. 61

An interview with the new

BSA Student Rep, James

McDaniel........p. 101

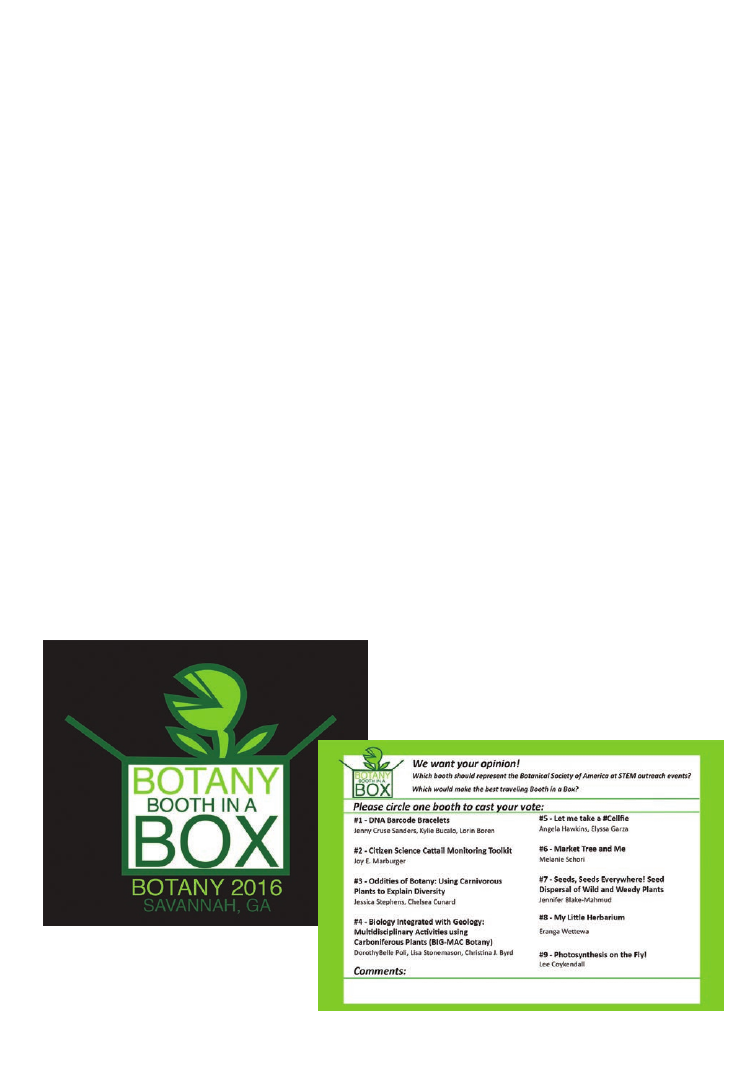

First place - Botany in a Box

Project!...p. 85

Fall 2016 Volume 62 Number 3

PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN

Editorial Committee

Volume 62

K ath ryn L eC roy

(2018)

Environmental Sciences

University of Virginia

Charlottesville, VA 22904

kal8d@virginia.edu

L .K . T u om inen

(2016)

Department of Natural Science

Metropolitan State University

St. Paul, MN 55106

Lindsey.Tuominen@metrostate.edu

D aniel K . G ladish

(2017)

Department of Biology &

The Conservatory

Miami University

Hamilton, OH 45011

gladisdk@muohio.edu

Melanie L ink - P erez

(2019)

Department of Botany

& Plant Pathology

Oregon State University

Corvallis, OR 97331

linkperm@oregonstate.edu

From the Editor

S h annon F eh lb erg

(2020)

Research and Conservation

Desert Botanical Garden

Phoenix, AZ 85008

sfehlberg@dbg.org

Greetings!

Two articles in this issue of Plant Science Bulletin

focus on the role and responsibility of the Botanical

Society of America in advocating for science educa-

tion. In this issue, BSA President Gordon Uno shares

his essay, “Convergent Evolution of National Sci-

ence Education Projects: How BSA Can Influence

Reform,” the first in a two-part series based on his

address at Botany 2016. Look for the second part

of this series to be published in Spring 2017. Also

included in this issue is the fourth part in Marshall

Sundberg’s series on Botanical Education in the

United States. This installment focuses on the role of

the Botanical Society in the late 20th and early 21st

centuries and showcases the society’s recent efforts

on the educational front. As always, we dedicate the

Education News and Notes section to the practical

efforts of the current BSA membership and staff to

promote science education at all levels and to help

lead the broader national conversation.

The discussion regarding the responsibility of indi-

vidual botanists and the BSA to promote botanical

education and engage both students and the general

public in our science has been of particular interest

for this publication since its inception. I’ve selected

two relevant passages “From the Archives” (page ##)

that illustrate the ongoing conversation within the

society. I encourage you to visit the PSB archives

(http://botany.org/PlantScienceBulletin/issues.

php#11) and read both of these excerpted articles in

their entirety.

I am encouraged by the fact that we, as a society, con-

tinue to grapple with the challenging questions of

how best to engage others in our science and educate

them in the issues that we care deeply about. I am op-

timistic that our thriving community of researchers,

educators, administrators, and students can continue

to effect positive change on the national stage if we

are intentional, thoughtful, and vigilant about pursu-

ing this component of the BSA mission.

113

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SOCIETY NEWS

Big Changes Coming to ASPT and BSA Policy Activities ................................................ 114

BSA Award Winners .................................................................................................................................. 118

PLANTS Grant Continues to Increase the Diversity of Plant Scientists .................... 121

The

American Journal of Botany is going online-only in 2017 ........................................ 124

Convergent Evolution of National Science Education Projects:

How BSA Can Influence Reform .................................................................................................. 125

SPECIAL FEATURE

Botanical Education in the United States. Part IV. The Role of the Botanical

Society of America (BSA) into the Next Millennium .......................................................... 132

SCIENCE EDUCATION

PlantingScience Launches New Website, Needs Volunteer Scientist Mentors! ..... 155

STUDENT SECTION

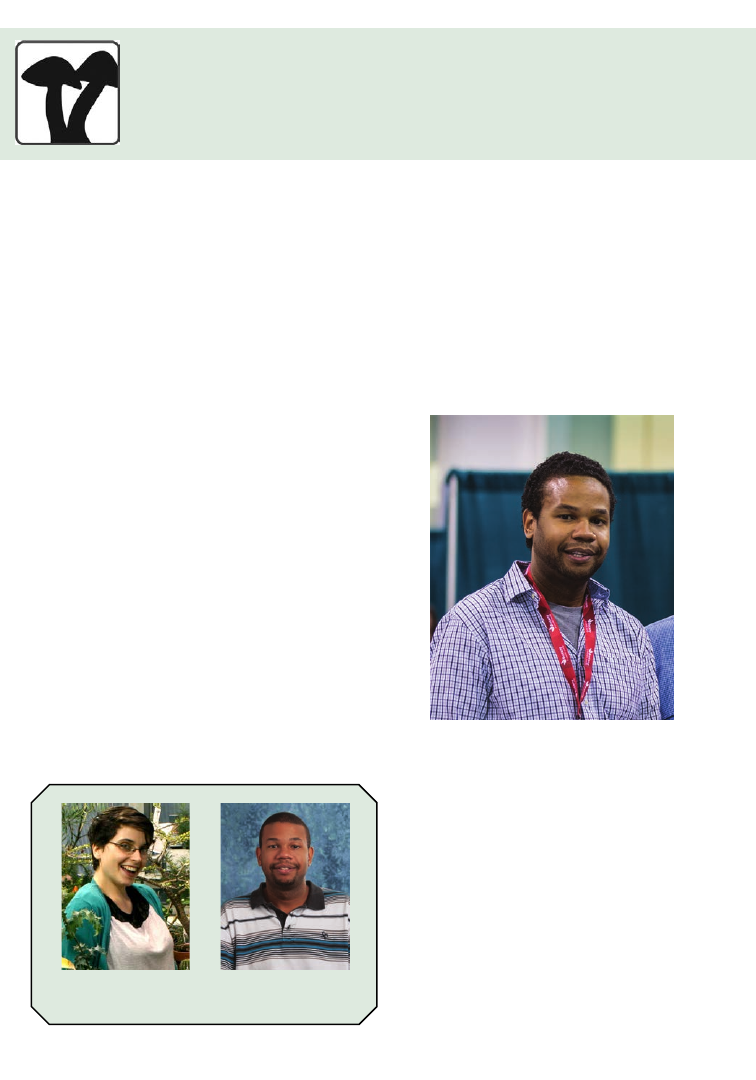

10 Years of Student Reps, and 10 Questions Featuring BSA’s New Student

Representative to the BSA Board, James McDaniel ....................................................... 159

ANNOUNCEMENTS

New Book Announcement from CABI: “Plant Biodiversity: Monitoring,

Assessment and Conservation” .................................................................................................. 163

Harvard University Bullard Fellowships in Forest Research .............................................. 163

Hunt Institute Director Robert W. Kiger Retires, T. D. Jacobsen

Becomes Director ............................................................................................................................... 164

The New York Botanical Garden and the Chrysler Herbarium Provide

Resources for Research on Ericaceae ................................................................................. 165

In Memoriam

Alfred Traverse. ..................................................................................................................................... 166

William D. Tidwell. ................................................................................................................................. 170

Sylvia "Tass" Kelso .............................................................................................................................. 171

John Melvin Herr, Jr ............................................................................................................................. 173

BOOK REVIEWS

Ecology ............................................................................................................................................................. 175

Economic Botany........................................................................................................................... ............. 178

Physiological..... ............................................................................................................................................. 181

Systematics ................................................................................................................................................... 183

114

SOCIETY NEWS

A joint report from the ASPT

Environmental and Public

Policy Committee and the

BSA Public Policy Committee

As part of a partnership between the ASPT

Environmental and Public Policy Commit-

tee and the BSA Public Policy Committee, we

have some big changes in store for opportu-

nities for membership engagement in public

policy issues, including new and upcoming

web resources as well as some expanded fund-

ing opportunities.

As a result of the partnership between ASPT

and BSA—the first ever co-sponsored award

program between our societies—we have

some announcements regarding new or ex-

panded opportunities for dissemination of

policy news and awards.

• New ASPT-BSA Policy awards officer,

Andrew Pais!

With new and expanded award opportunities

for environmental and public policy, one of

our committee members, Andrew Pais, has

been selected as Awards Officer. Andrew, a

Ph.D. Candidate at North Carolina State Uni-

versity, joined the BSA Public Policy Com-

mittee in 2014 after receiving the annual BSA

Public Policy Award to participate in the 2014

Congressional Visits Day. You can read about

Andrew’s experience in

the

Fall 2015 issue of

the Plant Science Bulletin. Having benefited

professionally from such an experience, An-

drew is excited to connect others with similar

opportunities.

• Botany Advocacy Leadership Grant

(BALG)

The BALG is in its second year, with our first

award going to ASPT and

BSA member Mike Dunn on

behalf of the Southwest chap-

ter of the Oklahoma Native

Plant Society to fund a lec-

ture series. This $1000 grant

can fund a variety of projects

that help educate the public

on the importance of botany

in environmental and public

policy issues or for communi-

ty-driven restoration projects

Big Changes Coming to ASPT and

BSA Policy Activities

By Marian Chau (Lyon Arboretum University of Hawai‘i at Mā-

noa) and Morgan Gostel (Smithsonian Institution), Public Policy

Committee Co-Chairs, along with Ingrid Jordon-Thaden (Uni-

versity of California Berkeley), ASPT EPPC Chair

PSB 62 (3) 2016

115

for botany groups. Applications for ASPT or

BSA members will be due by March 2017. Full

details can be found at: http://cms.botany.org/

home/awards/special-funds-and-awards/bot-

any-advocacy-leadership-grant.html.

• Congressional Visits Day (CVD) Public

Policy Award

This year in Savannah, the ASPT decided

to join the BSA in offering award funds for

ASPT members to attend and participate in

the annual Congressional Visits Day event.

ASPT will join BSA in sponsoring a member

to travel to Washington, DC and participate

in this important opportunity for science pol-

icy. This American Institute for Biological Sci-

ences (AIBS)–sponsored event asks scientific

societies to partially support selected mem-

bers to participate in the once-a-year visit to

Congress in Washington, DC, to learn about

governing and funding processes at the feder-

al level. Additionally, during the visit the AIBS

groups scientists together to physically meet

with members of Congress to impress upon

them the importance of federal funding for

biological sciences. ASPT has agreed to spon-

sor one ASPT member with $750, and BSA is

sponsoring two members with all expenses

paid (travel within USA only), to attend this

event in the spring of 2017. More informa-

tion can be found at: https://www.aibs.org/

public-policy/congressional_visits_day.html

• Botany Policy Network (BPN):

ASPT and BSA are working on developing a

web-based Botany Policy Network. This net-

work of concerned botanists, botany organi-

zations, and local plant groups will connect

the membership from ASPT and BSA with

people who want to share news, action alerts,

and interaction to better communicate and

respond to policy issues and events at all lev-

els—local, national, and international! We will

send an updated announcement about the

BPN and how we plan to carry out its creation

very soon in order to have it ready before next

year’s meeting in 2017.

The ASPT and BSA policy committees have

been very busy brainstorming how to best ed-

ucate both the public and our members in im-

portant and timely environmental and public

policy issues. We want to thank all of those

members who have provided us with ideas,

and most importantly to the voting members

of ASPT and BSA for agreeing to back these

efforts with funds. We are looking forward to

an excellent year!

PSB 62 (3) 2016

116

Very good meeting for me.

Good scientific program, nice opportunity

to get together with colleagues, and a

location that was fun and different!

Botany 2016 was a success!

Great Networking, Good Science,

Warm Southern Hospitality!

Your comments from the

post-conference survey....

Very nice conference, definitely one of the best.

Very interesting presentations, a good

offering of workshops & set in a very

beautiful & convenient location. Well done!

Great meeting!

Good scientific sessions,

lots of networking opportunities.

PSB 62 (3) 2016

117

I enjoyed the exhibits and

speaking with exhibitors.

It was nice to have the posters

surrounding the exhibitors.

The quality of posters was super.

Overall experience was great for

networking and career building.

Everyone was extremely helpful, great group of

organizers and volunteers, great assortment of

speakers with a lot of diversity in talks - I appre-

ciate the diversity since I teach a wide array of

classes in natural resource sciences.

This was one of the best

Botany conferences I can recall attending,

every talk and symposium

I went to was excellent.

PSB 62 (3) 2016

118

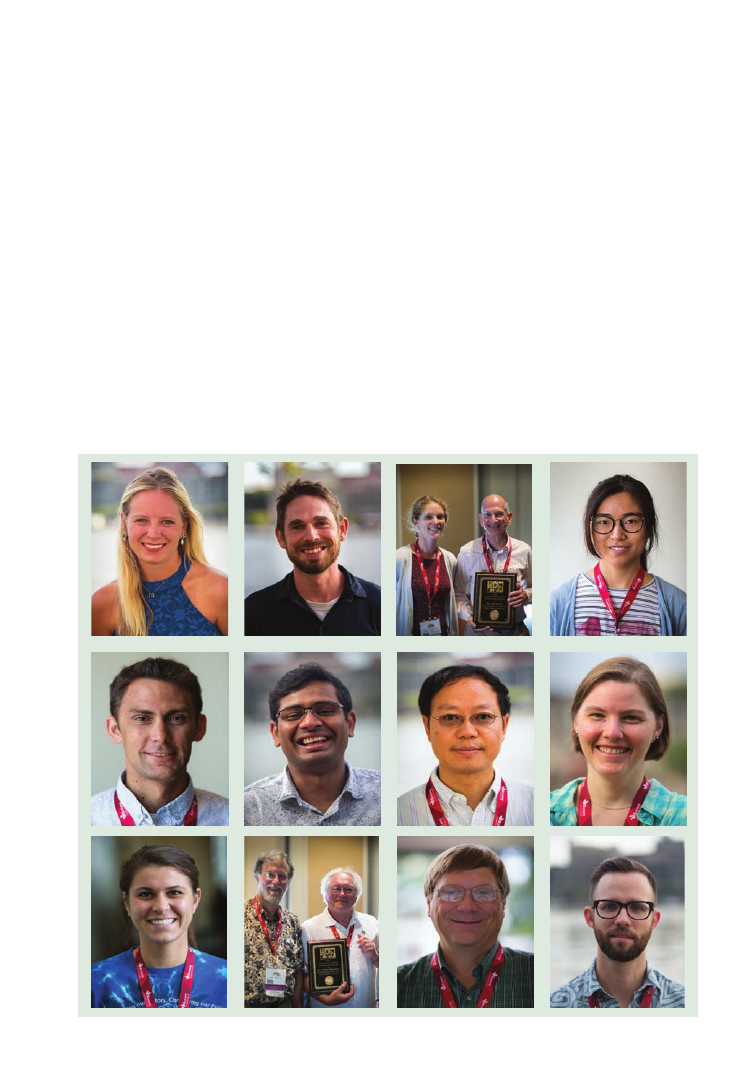

The previous PSB listed the award winners from Botany 2016 that were available at that time.

This is the remainder of the award recipients from the conference. Congratulations!

Jeanette Siron Pelton Award

The Pelton Award is given in recognition of sustained and creative contributions in plant mor-

phology. The award defines morphology broadly to include the subcellular, cellular and or-

ganismal levels of complexity, and will recognize experimental, comparative, and evolutionary

approaches.

Neelima Sinha, University of California, Davis

Samuel N. Postlethwait Award

This award is given for outstanding service to the BSA Teaching Section.

Stokes Baker, University of Detroit

Emanual D. Rudolph Award

Each year the Historical Section of the BSA offers an award for the best student presentation of

a historical nature at the annual meetings.

Aniket Sengupta, University of Kansas, for the presentation: “Calcutta Botanical Garden and

making of the modern world.”

Katherine Esau Award

This award was established in 1985 with a gift from Dr. Esau and is augmented by ongoing

contributions. It is given to the graduate student who presents the outstanding paper in de-

velopmental and structural botany at the annual meeting. The Esau award distributes $500 in

years in which the award is given.

Dustin Ray

, University of Connecticut, for the paper “Conduit packing and allometric scaling

of tissues in petioles.” Co-author: Cynthia Jones.

Developmental & Structural Section Best Student Presentation Award

Jingjing Tong, University of Washington, for the poster “Duplication and expression pattern of

CYCLOIDEA-like genes in Campanulaceae.” Co-author: Dianella Howarth

Tropical Biology Student Presentation

Samantha Worthy, Columbus State University, for the paper “Phylogenetic analysis of Andean

tree communities along an elevational gradient in Ecuador.” Co-authors: Rosa Jiménez, Renato

Valencia, Katya Romoleroux, Jennifer M. Cruse-Sanders, Alex Reynolds, John Barone, Alvaro

Perez, and Kevin Burgess

BSA AWARD WINNERS

PSB 62 (3) 2016

119

Ecology Section Student Presentation Awards

Ian Matthew Jones (Graduate Student), Florida International University, for the paper “Chang-

ing Light Conditions in Pine Rockland Habitats Affect the Outcome of Ant-Plant Interactions.”

Co-authors: Suzanne Koptur, Hilma R. Gallegos, Joseph P. Tardanico, and Patricia A. Trainer

Meghan Garanich (Graduate Student), Bucknell University, for the paper “Identification of fire

tolerance thresholds in seeds of the Western Australian endemic bush tomato, Solanum beaugle-

holei (Solanaceae)” Co-authors: Jason Cantley, Lacey Gavala, Ingrid Jordon-Thaden, and Chris

Martine

Scott Eckert, The College of New Jersey, for the best Graduate Student poster “Juvenile trees in

suburban forests: insights from structural equation modeling.” Co-author: Janet Morrison

Genetics Section Poster Award

The Genetics Section Graduate Student Research Award provides $500 for research funds and

an additional $500 for attendance at a future BSA meeting.

Michelle Gaynor, University of Central Florida, for the poster “Identifying the Factors Influenc-

ing Plant Communities Across the United States Using A Phylogenetic Framework.” Co-authors:

Robert Laport and Julienne Ng

Margaret Menzel Award

This award is presented by the Genetics Section for the outstanding paper presented in the con-

tributed papers sessions of the annual meetings.

Jason Cantley, Bucknell University, for the paper “Monolithic sandstone continental islands of

northern Australia unlock secrets of breeding system evolution in five sympatrically occurring spe-

cies of the Australian spiny Solanum (Solanaceae) lineage.” Co-authors: Ingrid Jordon-Thaden,

Morgan Roche, Daniel Hayes, and Chris Martine.

Maynard F. Moseley Award

The Maynard F. Moseley Award was established in 1995 to honor a career of dedicated teach-

ing, scholarship, and service to the furtherance of the botanical sciences. The award is given to

the best student paper, presented in either the Paleobotanical or Developmental and Structural

sessions, that advances our understanding of plant structure in an evolutionary context.

Alex Bippus, Humboldt State University, for the paper “Tiny ecosystems: bryophytes and other

biotic interactions around an osmundaceous fern from the Eocene of Patagonia.” Co-authors:

Ignacio H Escapa and Alexandru Tomescu

Physiological Section Student Presentation Awards

Katherine Cary, University of California, Santa Cruz (Advisor, Jarmila Pittermann), for the

paper “Leaf and xylem function under extreme nutrient deficiency: an example from the pygmy

forest.” Co-authors: Jarmila Pittermann

PSB 62 (3) 2016

120

Danielle Bucior, Ithaca College (Advisor, Dr. Brian Maricle), for the poster “Comparison of

Heavy Metal Concentrations in Terrestrial and Aquatic Plants from Vieques, Puerto Rico.”

Physiological Section Li-Cor Prize

Christina Hilt, Fort Hays State University (Advisor, Dr. Brian Maricle), for the poster “Does

environment or genetics influence leaf level physiology? Measuring photosynthetic rates of native

big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii) grown in common gardens across a precipitation gradient.”

Co-authors: Christina Hilt, Cera Smart, Adam Urban, Diedre Kramer, Nicole Martin, Sara

Baer, Loretta Johnson, and Brian Maricle

Isabel Cookson Award

Established in 1976, this award recognizes the best student paper presented in the Paleobotan-

ical Section.

Brian Atkinson, Oregon State University, for the paper “Initial radiation of asterids: earliest

cornalean fossils.” Co-authors: Ruth A. Stockey and Gar W. Rothwell

PSB 62 (3) 2016

121

PLANTS Grant Continues

to Increase the Diversity of

Plant Scientists

The PLANTS program (Preparing Leaders

and Nurturing Tomorrow’s Scientists) is

now in its sixth year. The program is funded

by the National Science Foundation with sup-

port from the BSA.

Currently managed by Co-PIs Ann Sakai

(UC-Irvine), Anna Monfils (Central Michi-

gan U), and Heather Cacanindin (BSA Mem-

bership and Subscriptions Director),

the goal

of the PLANTS program is to encourage stu-

dents from under-represented populations to

become part of the scientific botanical com-

munity—and in particular, to help them un-

derstand the opportunities possible with an

advanced degree and to learn about careers in

the plant sciences.

The program brings between 10 and 14 stu-

dents each year to the annual Botany con-

ference. PLANTS students attend scientific

talks with mentors, a workshop on applying

to graduate school, the Human Diversity Lun-

cheon, and numerous social and networking

events. With the assistance from Dr. Sakai

and Dr. Ann Hirsch (UCLA) as well as all

those who served on the PLANTS grant selec-

tion committee,

61 students have been funded

over the first five years of the PLANTS grant

(2011-2015).

In 2016,

11 students were select-

ed to attend the Botany 2016 Conference in

Savannah, Georgia.

At the core of the program are the mentors

who serve to guide the students through what

to expect at a scientific conference of this mag-

nitude. Each student is assigned a peer and a

senior mentor. Mentors contact students be-

fore the meeting, attend social activities and

scientific talks with the students, help the stu-

dents network with other students and faculty

at the meeting, and in general, introduce stu-

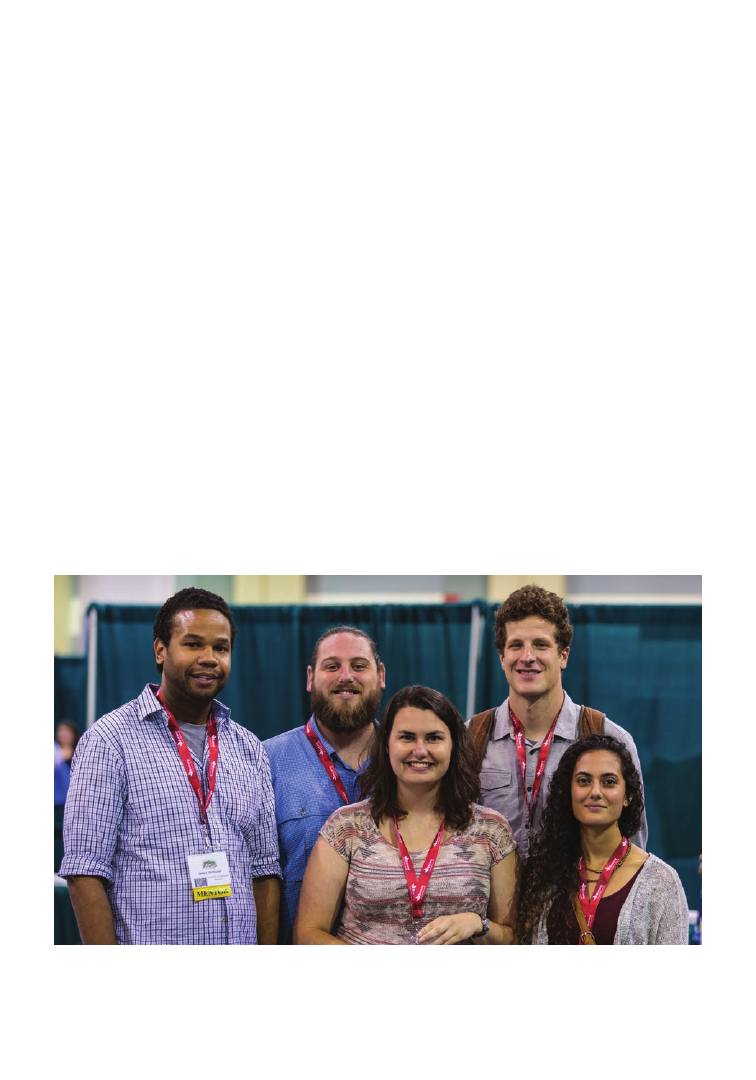

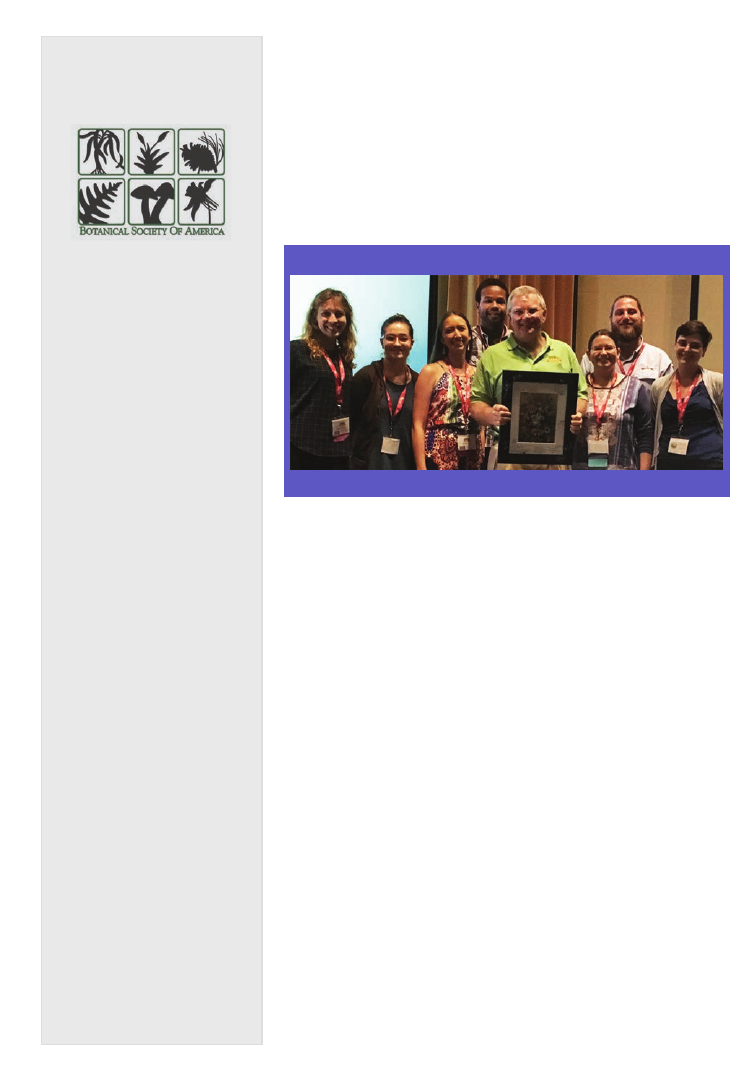

From left to right: Peer mentor James McDaniel (University of Wisconsin), peer mentor Jon

Giddens (University of Oklahoma), peer mentor Chelsea Pretz (University of Colorado Boul-

der), David Thomas (University of Oklahoma), and former PLANTS Grant recipient Maryam

Sedaghatpour (George Mason University).

PSB 62 (3) 2016

122

dents to the broader relevance and application

of the discipline. Mentors pass on to the stu-

dents the genuine intellectual excitement and

involvement of the conference participants.

In fact, many mentors maintain contact with

their mentees after the conference is over, pro-

viding insight and guidance on their career

path and assisting them with graduate school

and grant applications.

Our mentors are committed to helping young

scientists and increasing the diversity of plant

scientists. Mentors hail from government po-

sitions, small colleges, large research institu-

tions, and nonprofit organizations. They rep-

resent the variety of job opportunities in the

botanical sciences. A total of 81 different men-

tors participated in the program over the first

five-year grant period (42 senior mentors, 39

peer mentors, including 10 PLANTS alumni

who returned to participate as peer mentors).

They enthusiastically share their personal ex-

periences and expertise in the sciences and

serve without compensation or reimburse-

ment. The mentors are truly the backbone of

the PLANTS program and provide impactful

experiences for the PLANTS students.

One 2016 PLANTS recipient recently stated, “I

learned so much at the talks and much, much

more interacting with my two mentors and

others in the field. I lacked direction before

I attended and now feel much more certain of

my next several steps. I entered the conference

dissuaded against attending graduate school,

but with the guidance of [my mentors], I see

that’s where I will be next in order to reach my

professional goals.”

The PLANTS grant recipients have kept in

touch with the program for several years after

their participation, and this contact has been

critical to documenting the success of the stu-

dents and the program. Excluding the last co-

hort in 2015 because most of those students

just graduated within the last four months, for

the remaining four cohorts (N = 48), a total

of 71% (N = 34) began graduate school in ar-

eas related to the PLANTS program: N = 30

(62.5%) began doctoral programs, and N = 4

(8.3%) began masters programs.

Although most of these students had a

non-traditional profile for graduate school

based on grade point average, income, and

socioeconomic status, a very high proportion

of the 48 students earned prestigious fellow-

ships (N = 19, 40%), through NSF Graduate

Research Fellowships (N = 15, 31.3%), a Ford

Foundation Fellowship (N= 1, 2%), or institu-

tional 3- to 4-year-long institutional research

fellowships (N = 3, 6%). Two students from

the 2011 cohort also recently earned NSF

Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grants.

The success, enthusiasm, and contributions

of the PLANTS participants have helped to

make our botanical community more aware

and proactive about encouraging the diversity

of plant scientists within the Society and the

plant sciences as a whole. Moreover, a trans-

formation of the membership of the Botanical

Society has begun to occur as documented

by the increase in the diversity of our overall

membership. From 2011 to 2016, represen-

tation of BSA members who were American

Indian/Alaska natives, Pacific Islanders, and

African American/Black together rose from

<1% to 2.3%, and members who were Hispan-

ic or Latino/a rose from 2.3% to 3.8% of the

U.S. membership, for a total of 6.1% of U.S.

members.

Science will not thrive unless it is equally ac-

cessible to students from all backgrounds, in-

cluding those from groups that are currently

under-represented. Access involves knowl-

edge about the discipline, understanding the

culture of science, feeling welcome as a partic-

ipant in scientific endeavors and as a member

PSB 62 (3) 2016

123

of the scientific community, and understanding job opportunities in the area. The PLANTS

program continues to be successful in encouraging students from underrepresented back-

grounds to become part of our scientific community. The PLANTS program is just one part of

an overall growing effort by the Society to provide a range of professional development oppor-

tunities to our student members. Some of these efforts include hosting non-academic career

panels, workshops and symposia about science communication and dissemination, broader

impacts issues, and career speed dating.

When the call for applications comes out in February for the PLANTS Award, please carefully

consider those who you might encourage to apply for this opportunity. In May, we will again

be seeking peer and senior mentors for the 2017 cohort of PLANTS grant recipients. If you are

planning to attend Botany 2017 in Fort Worth, this could be a fantastic way for you to make

new connections and positively impact the life of an aspiring plant scientist. If you have any

questions about the program, please feel free to contact the BSA office at

bsa-manager@botany.

org

.

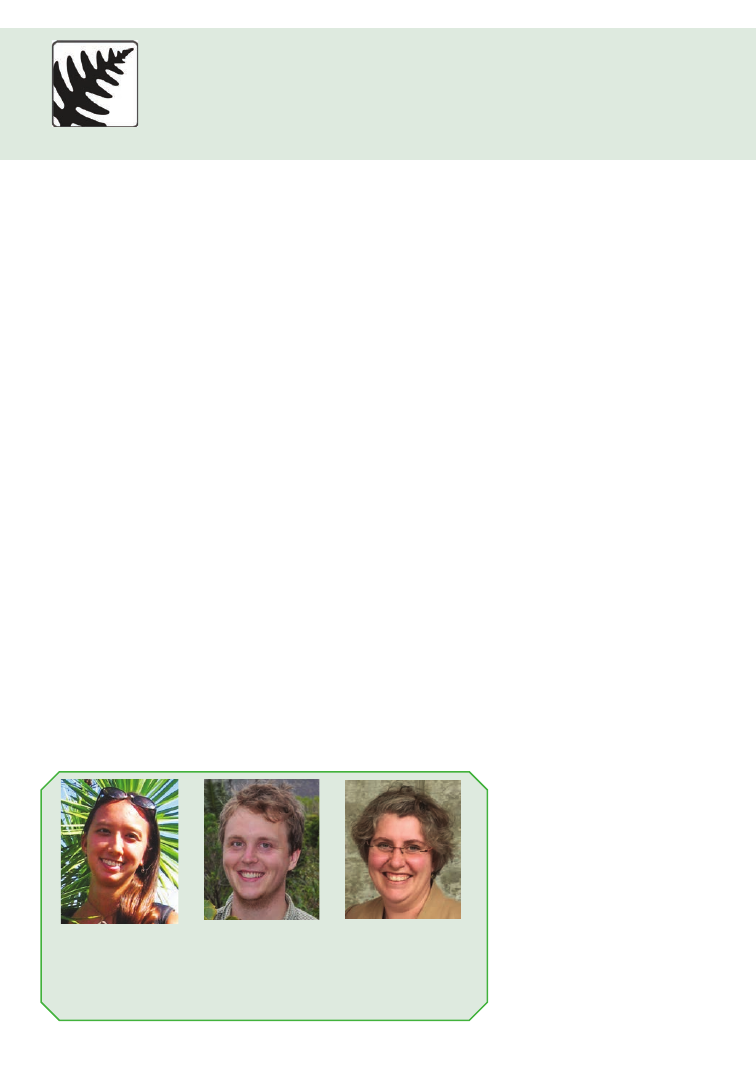

PLANTS Grant recipient Viviana Sanchez (left) from Mount St. Mary’s University is joined by

peer mentor Kelly Matsunga (University of Michigan) and senior mentor Suzanne Koptur (Flori-

da International University) at Botany 2016.

PSB 62 (3) 2016

124

The

American Journal of

Botany is going online-only

in 2017

The BSA is pleased to join with other scien-

tific societies in our community by reducing

our joint global carbon footprint. In 2017, the

American Journal of Botany will move to on-

line-only publication. As part of online-only

publishing, we will continue to support botan-

ical research by introducing new features and

improved functionality for both readers and

authors. In addition to being a greener pub-

lishing option, this move will allow the Soci-

ety to direct a portion of print costs to invest

in new opportunities to support our members

and the botanical sciences.

Highlights from 2016 include important and

timely articles on plant phylogeny, develop-

ment, and evolution, as well as three special

issues focused on insights from studies of

geographic variation, pollen performance,

and polyploidy, and a special section on the

interactions between plants and their mutu-

alist partners. The essay series “On the Nature

of Things” (“OTNOTs” for short) continues to

spark insights on a broad range of topics and

is being read and discussed by people around

the world. We look forward to serving our au-

thors, the botanical community, and broader

readership in 2017.

Your Society

publications want you!

The BSA encourages you to send your

strongest work to your Society publica-

tions:

• American Journal of Botany publishes

peer-reviewed, innovative, significant re-

search of interest to a wide audience of

plant scientists in all areas of plant biolo-

gy, all levels of organization, and all plant

groups and allied organisms. To submit a

paper, go to http://ajb.edmgr.com/.

• Applications in Plant Sciences is a monthly

open access, peer-reviewed journal pro-

moting the rapid dissemination of newly

developed, innovative tools and protocols

in all areas of the plant sciences, including

genetics, structure, function, development,

evolution, systematics, and ecology. To sub-

mit a paper, go to http://apps.edmgr.com.

• Plant Science Bulletin is an informal com-

munication for Society members pub-

lished three times a year, with information

on upcoming meetings, courses, field trips,

news of colleagues, new books, and pro-

fessional opportunities. It also serves as a

forum for circulating BSA committee re-

ports and discussing issues of concern to

Society members such as environmental

policy and educational funding. Research

articles may be submitted to http://psb.ed-

mgr.com/.

Your Society publications can only suc-

ceed with your help. If you have queries

or ideas for essay, research article, or spe-

cial issue contributions, please contact

the editorial offices at ajb@botany.org;

apps@botany.org; or psb@botany.org.

PSB 62 (3) 2016

125

Society News

I have been interested and engaged in science

education since my undergraduate studies at

the University of Colorado, when I worked

with the BSCS (Biological Sciences Curricu-

lum Study), then located near Boulder, while

working on my undergraduate degree in Biol-

ogy. During my graduate program at the Uni-

versity of California, Berkeley, my research

was on the reproductive biology and polli-

nation ecology of Iris douglasiana, a coastal

Iris species, but my financial support came as

a teaching assistant and then lead TA for the

Introductory Biology program at UCB (with

24 laboratory sections). So, while I was con-

ducting botanical research, I was still engaged

in science education activities. I carried my

interests with me to the University of Oklaho-

ma, where I have taught over 10,000 students

in Introductory Botany. There are two points

to this introduction: (1) I have been involved

in science education for a very long time, and

I have seen it change dramatically over the

years; and (2) I have been able to combine my

interests in science and science education into

a career, and this pathway is now being fol-

lowed by many others at institutions around

the country.

The Centrality of Education

in the Mission of the

Botanical Society of America

In 2012, the American Institute of Biological

Sciences (AIBS) released the results of a sur-

vey of nearly 100 leaders of scientific societ-

ies on their perceived role of these societies

today (Box 1) (Musante and Potter, 2012). I

would argue that every single role identified

on the list generated by these scientists has a

major educational component or focus. For

example, the first identified role for a scien-

tific society is “Advancing Research,” which

conferences, such as our annual BSA meeting,

obviously help to do. However, the knowl-

edge transfer that occurs at our annual con-

ference is also an educational activity—we are

teaching each other about the latest findings

in multiple areas of research, as well as new

techniques and methods of investigation. In

addition, we have those with knowledge in-

forming those who seek knowledge, which

is one component of education. In terms of

Convergent Evolution of National

Science Education Projects:

How BSA Can Influence Reform

Remarks from Botany 2016 by President-Elect

Gordon E. Uno

By Gordon E. Uno,

BSA President-Elect

University of Oklahoma

PSB 62 (3) 2016

126

Society News

the second identified role, “Promoting Col-

laboration and Networking,” as we begin to

form these interactive efforts, we have to in-

form each other of what we know and what

we want to understand; we must educate each

other about our strengths and questions we

have and how we can contribute to the col-

laboration or network. “Building Public

Understanding of Science” and “Promoting

Informed Policy” are also educational activi-

ties—albeit with different audiences than that

found in a typical classroom, and which are

activities that scientists are often woefully

underprepared for or unwilling to engage in.

Thus, I strongly believe that education is and

should be a primary focus of any scientific so-

ciety, including BSA, in all of the activities in

which its members are engaged.

An educational focus is also found embedded

in all of the Challenges to Biology as a dis-

cipline (Box 2), as identified from the same

AIBS survey. The lack of appropriate educa-

tion plays a major role in the alarming level of

scientific illiteracy illustrated by segments of

the general public, and some politicians, and

is troublesome to all scientific endeavors, fu-

ture funding of science, as well as our national

competitiveness in a scientific and technolog-

ical world (Clough, 2011). Thus, as a scientific

society, BSA is faced with the same challeng-

es as identified in the BioScience survey, and

therefore we must ensure we emphasize and

improve the educational aspects of all the

roles we play as a society. We also need to un-

derstand the educational responsibilities we

have as we address the grand challenges facing

contemporary Biology and Botany.

Our Educational Roles as

Scientists and Botanists

As seen above, our educational activities and

influences extend well beyond our classrooms.

We have a major responsibility to educate the

general public about plants and science. This

was the theme of one symposium at this year’s

BSA conference, “The Importance of Com-

municating Science.” The overall sentiment

expressed by all speakers in this symposium

was that scientists are often not very good

about communicating their science to the

public, and that we all need to do a better job

in this important activity.

Box 1. Seven of the Primary Roles of Scientific Societies Today. Results from

the AIBS Survey of Science Society Leaders. (Musante and Potter, 2012)

1. Advance research or knowledge transfer

2. Promote or facilitate collaboration or networking

3. Advance education

4. Build public understanding and informal education opportunities

5. Promote informed policy or advocacy

6. Empower student success for a future in the field—diversity and careers

7. Promote conservation or wise use of resources

PSB 62 (3) 2016

127

Educating our colleagues and administrators

is also a critical activity for all plant biologists.

Not understanding the importance of our re-

search can lead to decisions at funding agen-

cies that jeopardize future support. I point to

the hiatus in the NSF program, Funding for

Collections in Support of Biological Research,

as an example of the lack of informed commu-

nication between the administrators in charge

of funding decisions and the community that

is affected by these decisions—issues directly

related to two of the Greatest Challenges to

Biology (see Box 2). Another example of the

importance of continuous informal education

of our colleagues comes from the time when

I was Chair of the Department of Microbi-

ology and Plant Biology at the University of

Oklahoma. I feel it was critical to the hiring of

additional botanists to constantly remind my

microbiological colleagues and our Universi-

ty’s administration about the importance of

plant research. One of the documents I used

in the defense of botany was the NRC’s 2009

document, “A New Biology for the 21

st

Centu-

ry,” in which you will find the four grand re-

search challenges in Biology for the 21

st

Cen-

tury identified by an expert panel of scientists.

Those grand challenges in biology include:

(1) generate food plants to adapt and grow

sustainably in changing environments; (2) un-

derstand and sustain ecosystem function and

biodiversity in the face of rapid change; (3)

expand sustainable alternatives to fossil fuels;

and (4) understand individual health. When

one considers nutrition and medicinal plants

as part of understanding individual health, an

argument can easily be made that plant re-

search will play a large role in solving all the

challenges that have been identified for our

nation’s near and distant future. I think my

strategy was fairly successful: during my 15

years as Chair of the Department, we hired 19

Box 2. Ten of the Greatest Challenges to Biology as Identified by Scientific

Society Leaders. (Musante and Potter, 2012)

1. Decision-makers not informed about biological research or issues

2. Lack of funding for research

3. Public’s lack of appreciation for biology

4. Rejection of evolution as the central tenet of biology

5. Quantity and quality of jobs for trained biologists

6. Lack of advocacy for science funding

7. Failure to educate non-majors to engage in lifelong appreciation of biology

8. Lack of support for biologists to teach or participate in community out-

reach activities

9. Fragmentation of biological disciplines

10. Decreasing science coverage in popular media

PSB 62 (3) 2016

128

faculty, and by the end of my tenure as Chair,

we had the greatest number of botanists in the

history of the unit. (In addition, we had the

greatest percentage of women of any science

or engineering department, and out of all 76

academic units on campus, we had the highest

amount of external funding—for several years

in a row.) The point here is that we should not

automatically assume that our colleagues, and

certainly our administrators, have a working

knowledge and positive attitude about the bo-

tanical research we do and why it is import-

ant. Thus, we must constantly educate them

about our botanical activities.

The third important educational role that

plant biologists play is directly related to our

instructional role, helping students learn

about plants, biology, and science. I think

that botanists have a good understanding of

the problems we all face in the classroom—

undergraduate students don’t have a huge in-

terest in majoring in botany when they come

to college, even if they want to major in some

area of biology (Marbach-Ad, 2004). In addi-

tion, people in general have “plant blindness,”

which is the inability to see or notice plants

in one’s own environment, leading to a lack of

understanding of the importance of plants in

the biosphere and in the life of humans (Wan-

dersee and Schussler, 1999). So we botanists

start with a disadvantage as we try to entice

students to major in plant biology or to take

one of our courses.

We are also aware of many identified issues

with science courses and with incoming stu-

dents and the way they are taught, such as

the absence of critical thinking or inquiry in

courses and the few opportunities for stu-

dents to engage in independent research, dis-

cuss complex topics, or experience science as

a process in class. After taking our courses,

students often leave their undergraduate pro-

gram with little ability in critical thinking,

complex reasoning, and writing skills (Arum

and Roksa, 2011). These problems in the

classroom contribute to the scientific illiteracy

of the general public, issues related to finding

enough qualified graduate students, funding

issues for science research, poor training of

future science teachers, faculty frustration in

teaching, and students leaving biology and

botany programs for other careers. Several

national science education reform projects

have emerged over the years, each working

independently to solve the issues of science

education in different arenas. This is part of

the good news in terms of science education,

and I will address what these projects have in

common. But first, I would like to discuss how

we got to this point. The myriad problems in

teaching and learning science were the impe-

tus for people to initiate large-scale, national

science education reform projects. But there

has also been a slowly building revolution in

terms of the concern about and participation

in science education reform by faculty not ini-

tially trained, but still interested, in education.

I think we have reached the tipping point in

terms of interest, action, and acceptance of

science education in scientific academic circles

Reaching the Tipping Point

for Science Education

The tipping point, according to Malcolm

Gladwell (2000), is the critical point in a situ-

ation, process, or system beyond which a sig-

nificant and often unstoppable change takes

place. I think we have reached this change

due to a number of factors. I will now detail

eight pieces of evidence that we have reached

the tipping point in terms of support for and

involvement in science education research

and activities.

PSB 62 (3) 2016

129

First, there are more “pure” scientists (those

who have no formal training in science edu-

cation research) who have become concerned

about problems in science education and who

have contributed to science education reform.

For instance, as President of the National

Academy of Science, Bruce Alberts was deep-

ly engaged in science education reform issues,

including championing the new Next Gener-

ation of Science Standards from the NRC and

the redesign of the College Board’s Advanced

Placement science courses. Two of the last ed-

itors for Science, Alberts and Marcia McNutt,

have frequently written editorials about sci-

ence education (e.g., Alberts and McNutt,

2013). Carl Weiman, 2001 Nobel Prize win-

ner in Physics, has written about the appli-

cation of new research to improve science

education (2012). Jo Handelsman, currently

Associate Director for Science in the White

House Office of Science and Technology Pol-

icy (OSTP), has promoted “scientific teach-

ing” (Handelsman, Miller, and Pfund, 2007),

which is instruction that mirrors science at its

best; that is, teaching that is experimental, rig-

orous, and based on evidence. This method

requires all instructors to reflect on our own

teaching methods in order to determine “how

do we know that what we are doing is helping

our students learn?”

A second piece of evidence in regard to reach-

ing the tipping point is the growing body of

high-quality, rigorous, peer-reviewed science

education literature found in an increasing

number of quality science education journals,

such as CBE-Life Sciences Education, a journal

published by the American Society for Cell Bi-

ology. These journals and articles are reveal-

ing what is called “evidence-based teaching,”

which Handelsman and others have empha-

sized as the way to engage students in science.

Third, there is an increasingly large number

of science faculty with education specialties

(SFES) faculty found embedded in biology

departments around the country. In 2013,

there were 841 Biology SFES at PhD-granting

institutions of higher education (Bush et al.,

2013), many in tenure-track positions. Some

of these faculty were trained as science educa-

tion researchers, some as biologists who be-

came interested in science education, but they

all contribute to the science education litera-

ture and/or help colleagues to improve their

teaching. This means that members of science

departments frequently have colleagues with

education expertise down the hall from them,

which facilitates communication and interac-

tions.

While we know, to some

degree, what works in

a science classroom to

help students learn and

understand biology, we

know less about how

to help more faculty

effectively implement

these methods in their

courses.

Fourth, teaching and learning centers have

developed at most colleges and universities,

and they have emerged as places where fac-

ulty professional development takes place—

and more faculty are seeking the services of

these centers to help them improve their in-

structional practices. Fifth, we have a much

better understanding of how people learn

(from the perspective of cognitive sciences)

and about the biology of learning (from the

perspective of the neurosciences). Examples

of books that illustrate this better understand-

PSB 62 (3) 2016

130

ing include two from the National Research

Council, “How Students Learn: Brain, Mind,

Experience, and School” (Bransford, Brown,

and Cocking, 2000) and “How Students

Learn: Science in the Classroom” (Dono-

van and Bransford, 2005). Sixth, universities

across the country are experimenting with

different, and better, ways of preparing the fu-

ture professoriate by educating graduate stu-

dents more broadly. That is, faculty mentors

are working with these doctoral candidates

to develop their teaching philosophy and to

cultivate their instructional talents. From the

years 1999-2011, the NSF GK-12 program

launched the careers of thousands of graduate

students by supporting their collaborations

with K-12 teachers and students during their

science graduate degree program. Emerging

from this and other efforts are new models of

graduate education that integrate teaching/

learning with science research and often en-

gage graduate students in the scholarship of

teaching, which many students continue into

their first professional positions (Trautman

and Krasny, 2006).

The seventh sign that we have reached the

tipping point also has to do with funding

agencies, such as NSF, and scientific societies

that are developing and supporting science

education activities and programs. In addi-

tion, and as you might expect, there are sev-

eral major science education organizations

such as the National Association of Biology

Teachers (NABT) that are working on large-

scale projects to support improved instruc-

tion at the undergraduate level. In terms of

funding agencies, I have already mentioned

GK-12; however, the NSF has also initiated

the Research Coordination Networks in Un-

dergraduate Biology Education (RCN-UBE)

program. RCN-UBE projects support the

development of groups of individuals who

are working to solve problems and agree on

standards of a particular aspect of science ed-

ucation, such as how to incorporate the use of

bioinformatics into an undergraduate degree

program (Eaton et al., 2016). A new research

society, the Society for the Advancement of

Biology Education Research (SABER), has

developed from an RCN-UBE award and now

holds annual conferences with 500 conferees.

All of the larger scientific societies, such as

BSA, the Ecological Society of America, and

the American Society for Microbiology, have

active education departments that engage in a

wide variety of outreach activities and support

for their members regarding teaching and sci-

ence education.

One of my three RCN-UBE awards, the Intro-

ductory Biology Project (IBP), was a 5-year

networking project that engaged several hun-

dred faculty around the country to discuss the

myriad problems associated with the first, and

often only, biology course college students

take (Eaton et al., 2016). The project result-

ed in publications, new collaborations among

the participants, new projects emerging from

interactions of faculty who attended the IBP

meetings, as well as a summit attended by

representatives of all the RCN-UBE awards

to date (NSF RCN-UBE award to Uno, PI,

2015). From the IBP we have learned what

makes networks and collaborative efforts

work, which should inform any society as it

attempts to develop interactive groups of sci-

entists (Eaton et al., 2016). Another meeting

that emerged from my IBP was a Gordon Re-

search Conference on Undergraduate Biology

Education Research (UBER). This is current-

ly the only GRC dealing with biology educa-

tion in the GRC portfolio (see the GRC web-

site at www.grc.org). Susan Elrod (Provost at

University of Wisconsin-Whitewater) and I

(co-Chair and Chair, respectively) chose the

theme of “translational research” for the first

GRC UBER—that is, while we know, to some

PSB 62 (3) 2016

131

degree, what works in a science classroom to

help students learn and understand biology,

we know less about how to help more faculty

effectively implement these methods in their

courses. We wrote the successful proposal to

the GRC, and we were also successful in ob-

taining supporting funds from the NSF, NIH,

the HHMI, as well as the GRC to support the

conference. All of these results are indicators

of the continued support shown by science or-

ganizations and funding agencies for science/

biology education. The next GRC UBER will

be held at Stonehill College, MA, in the sum-

mer of 2017 and has a theme of “Improving

Diversity, Equity, and Learning.” For those

interested in attending, please visit the GRC

website.

The final piece of evidence regarding the tip-

ping point is related to the title of this talk—

the convergent evolution of several major

national science education reform efforts. I

will deal with this convergence in Part 2 of

this article, discussing what these large-scale

projects have in common. In addition, I will

make a few recommendations about how the

BSA can promote educational reform within

the society and for our members.

Literature Cited

Alberts, B. and M. McNutt. 2013. Science demy-

stified. Science 342: 289.

Arum, R. and J. Roksa. 2011. Academically

Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses.

The University of Chicago Press. 272 pp.

Bransford, J. D., A. L. Brown, and R. R. Cocking

(eds). 2000. How People Learn: Brain, Mind,

Experience, and School. The National Academies

Press. 384 pp.

Bush, S. D., N. J. Pelaez, J. A. Rudd, M.T. Ste-

vens, K.D. Tanner, and K.S. Williams. 2013.

Widespread distribution and unexpected variation

among science faculty with education specialties

(SFES) across the United States. Proceedings of

the National Academy of Sciences 110 (18): 7170-

7175.

Clough, G. W. 2011. Increasing Scientific Liter-

acy: A Shared Responsibility. Smithsonian Insti-

tution. 68 pp.

Donovan, M. S. and J. D. Bransford (eds). 2005.

How Students Learn: Science in the Classroom.

The National Academies Press. 264 pp.

Eaton, C., D. Allen, L. Anderson, G. Bowser, M.

Pauley, K. Williams, and G. Uno. 2016. Summit

of the Research Coordination Networks for Un-

dergraduate Biology Education. CBE—Life Sci-

ences Education (accepted for publication).

Gladwell, M. 2000. The Tipping Point: How

Little Things Can Make a Big Difference. Little,

Brown and Company. 304 pp.

Handelsman, J., S. Miller, and C. Pfund. 2007.

Scientific Teaching. Macmillan. 184 pp.

Marbach-Ad, G. 2004. Expectations and diffi-

culties of first-year college students in biology.

Journal of College Science Teaching 33: 18-23.

Musante, S. and S. Potter. 2012. What is import-

ant to biological societies at the start of the Twen-

ty-first Century? BioScience 62(4): 329-335.

Trautman, N. M. and M. E. Krasny. 2006. Inte-

grating teaching and research: a new model for

graduate education? BioScience 56: 159–165.

Wandersee, J. H. and E.E. Schussler. 1999. Pre-

venting plant blindness. American Biology Teacher

61: 82-86.

Weiman, C. 2012. Applying new research to im-

prove science education. Issues in Science and

Technology 29 (1). Fall Issue.

132

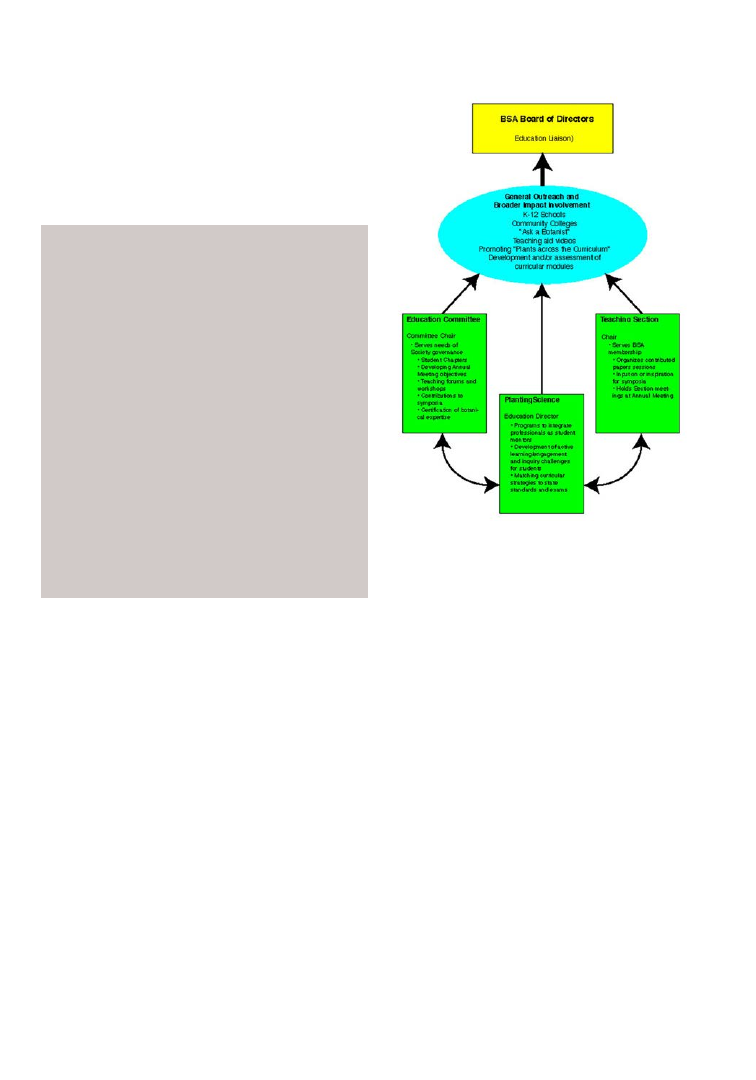

SPECIAL FEATURE

Abstract

During its second half-century, the educa-

tional activities of the Botanical Society of

America (BSA) can be divided into three

main periods. The first, associated with the

founding of the American Institute of Bio-

logical Sciences (AIBS), and especially the

Commission for Undergraduate Education in

Biological Sciences (CUEBS), rekindled the

interest and participation of some of BSA’s

most notable members in improving botani-

cal education. Several of their ideas ultimately

came to fruition at the end of the century. Sec-

ond, with the demise of CUEBS, a new group

Botanical Education in the

United States.

Part IV. The Role of the Botanical

Society of America (BSA) into the

Next Millennium

1

of botanical educators began to work through

AIBS to promote BSA’s educational agenda.

Third, in the mid-1990s, as BSA moved to-

ward an independent and more professional

business and meeting model, it also focused

on strengthening botany as a discipline as the

Society moved into the next millennium and

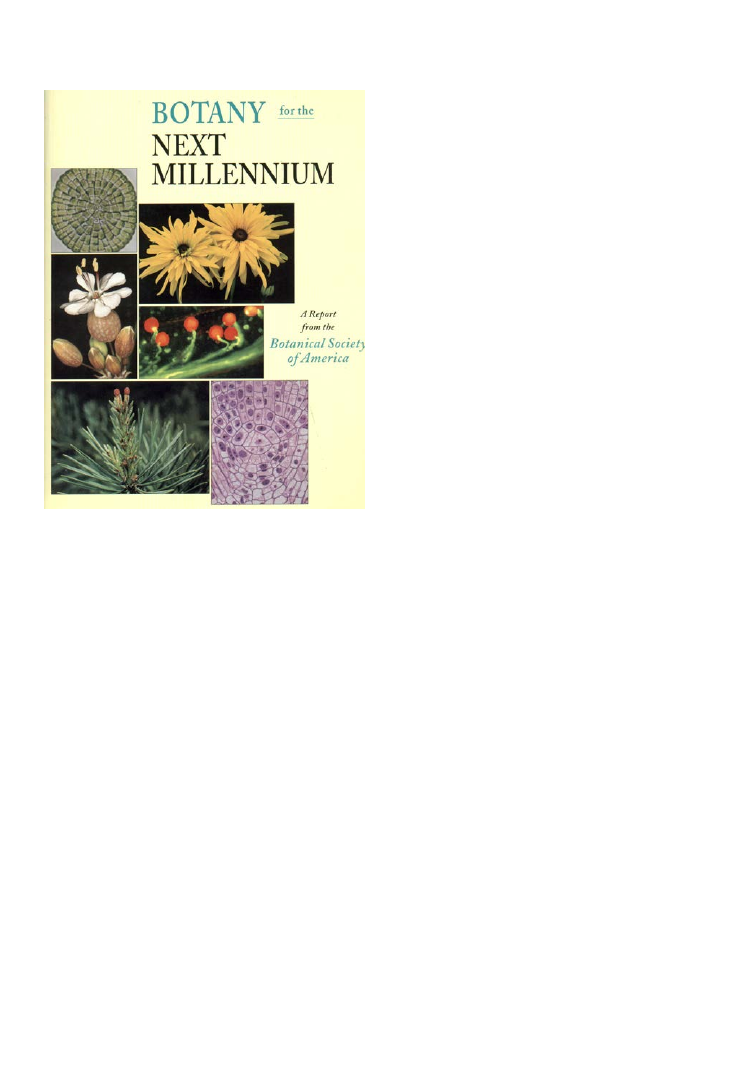

into its next century. The resulting Botany for

the Next Millennium provided the framework

for BSA educational activities up to the pres-

ent day

Key Words:

botanical education; CUEBS; educational forum;

inquiry-based learning; PlantingScience

Footnotes

1 Received for publication 22 June 2016; revision ac-

cepted 18 August 2016.

2 Corresponding author email: msundber@emporia.edu

doi: 10.3732/psb.1600003

By Marshall D. Sundberg

2

Department of Biology,

Emporia State University,

Emporia, KS

PSB 62 (3) 2016

133

A

s noted in the previous part of this series,

a striking characteristic of botanical ed-

ucation in the Society during its first 50 years

was alternating periods of waxing and waning

interest (Sundberg, 2014). This general pattern

of waxing and waning has not changed during

the Society’s second half-century, but the

drivers have (Fig. 1). Particularly noteworthy

during the first half-century of the Society was

the major role played by leading botanists, in-

cluding several Presidents of the Society, who

drove a botanical education agenda (the nota-

ble outliers since 1956 are former Presidents

Harriett Creighton, who was active during the

transition region, and William Jensen, as well

as current President, Gordon Uno) (Table 1).

As noted previously, this had already begun to

change by the 50th anniversary of the Society,

and it was in large part linked to the evolu-

tion of the American Institute for Biological

Sciences (AIBS) (Sundberg, 2014). The Teach-

ing Section was established in 1947, the year

before the founding of AIBS. The BSA was a

charter member of AIBS, and BSA Past Presi-

dent, Ralph Cleland, was its first Board Chair-

man (AIBS, 1972; DiSilvestro, 1997).

Many AIBS programs, including in educa-

tion, were closely tied to developments in the

BSA, and the peaks of educational activity

in the late 1960s and mid-1990s reflect this

close connection with BSA members driving

programs both in AIBS and BSA (see Fig. 1).

The BSA Education Committee was estab-

lished in 1951, and from its inaugural issue

in 1955, Plant Science Bulletin provided a fo-

cus on botanical education issues (Sundberg,

2014). AIBS followed suit by establishing its

Committee on Education and Profession-

al Recruitment in 1956 with BSA immedi-

ate Past-President Oswald Tippo as its chair

and BSA President Harriett Creighton and

BSA member Ronald Bamford as committee

members (Cox, 1956). Close program links

between AIBS and BSA were facilitated by the

fact that BSA met as an affiliate society during

Figure 1. Educational Activities of BSA through its second half-century.

PSB 62 (3) 2016

134

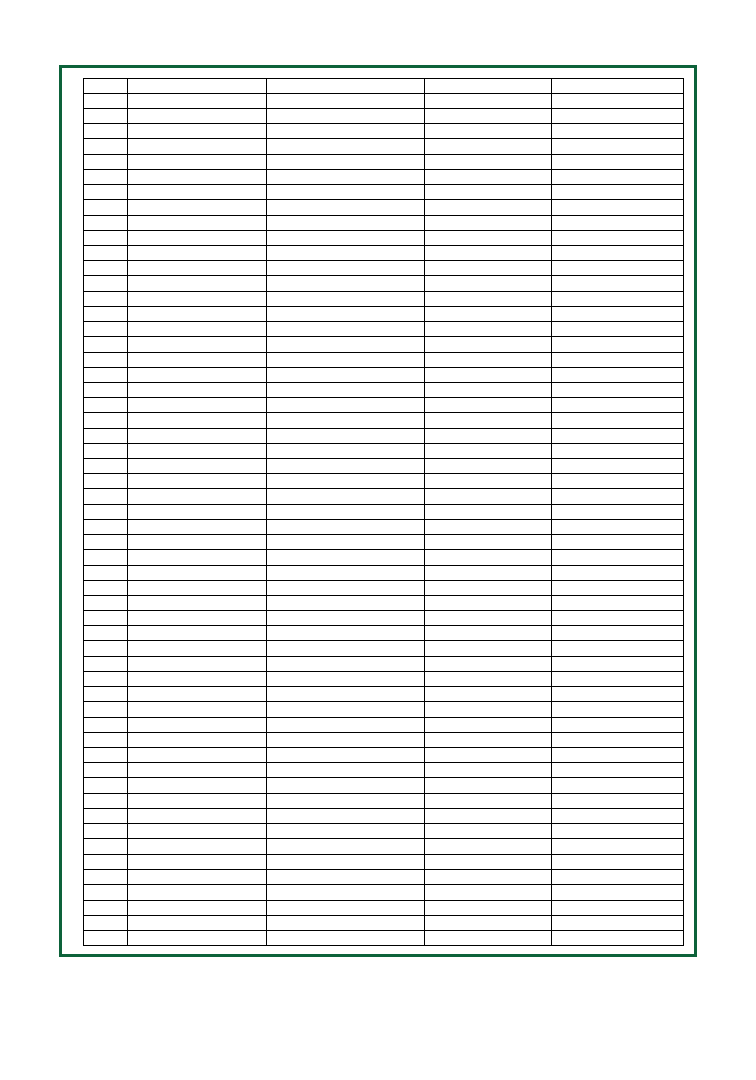

Table 1 Chairpersons of BSA Teaching Section and Education Committee*

*Continued from Table 6 in Sundberg, 2014 (p. 46).

Year

Teaching Section

Education Committee

Director-at-Large

Education Staff Person

1960

Harriette V. Bartoo

Victor Greulach /John Torrey?

1961

William B. Drew

Harriett B. Creighton

1962

Samuel N. Postlethwait

Harriett B. Creighton

1963

Robert W. Hoshaw

Adolph Hecht

1964

Robert W. Hoshaw

Adolph Hecht

1965

Robert C. Lommasson

Adolph Hecht

1966

Paul A. Vestal

Samuel N. Postlethwait

1967

Helena A. Miller

Samuel N. Postlethwait

1968

J. Louis Martens

Samuel N. Postlethwait

1969

Irving W. Knoblock

Richard M. Klein

1970

Irving W. Knoblock

Richard M. Klein

1971

J. Louis Martens

Richard M. Klein

1972

Orie J. Eigsti

Peter B. Kaufman

1973

Sanford S. Tepper

Peter B. Kaufman

1974

Donald S. Dean

J. Donald La Croix

1975

Willis H. Hertig

Willard W. Payne

1976

William A. Jensen

Sanford S. Tepper

1977

Franklin F. Flint

Janice C. Coffey

1978

Donald M. Huffman

Charles R. Curtis

1979

Charles R. Curtis

Shirley A. Graham

1980

Barnett N. Rock

Richard A. White

1981

W. Moser Hess

Franklin F. Flint

1982

Roy H. Saigo

Samuel N. Postlethwait

1983

Louis H. Tiffany

Samuel N. Postlethwait

1984

Alan R. Orr

Barbara W. Saigo

1985

David T. Webb

Roy H. Saigo

1986

Marshall D. Sundberg

Roy H. Saigo

1987

Gordon E. Uno

John A. Novak

1988

John A. Novak

Edith S. Taylor

1989

Steven G. Saupe

Jeanette S. Mullins

1990

Jan Balling

Thomas L. Rost

1991

Jeanette S. Mullins

Thomas L. Rost

1992

Donald S. Galitz

Marshall D. Sundberg

1993

Kenneth J. Curry

Marshall D. Sundberg

1994

David W. Kramer

Bruce K. Kirchoff

1995

Stanley A. Rice

Steven G. Saupe

1996

Eileen D. Bunderson

David W. Kramer

1997

Robert J. (Rob) Reinsvold David W. Kramer

1998

Robert J. (Rob) Reinsvold David W. Kramer

1999

Robert J. (Rob) Reinsvold David W. Kramer

2000

Robert J. (Rob) Reinsvold David W. Kramer

2001

Henri Maurice

David W. Kramer

2002

Henri Maurice

Robert J. (Rob) Reinsvold

2003

Daniel T. (Tim) Gerber

Robert J. (Rob) Reinsvold

2004

James E. Mickel

Gordon E. Uno

2005

Beverly J. Brown

Gordon E. Uno

2006

Beverly J. Brown

Gordon E. Uno

Claire A. Hemingway

2007

James H. Wandersee

Gordon E. Uno

Claire A. Hemingway

2008

James H. Wandersee

Gordon E. Uno

Claire A. Hemingway

2009

James H. Wandersee

Beverly J. Brown

Christopher H. Haufler

Claire A Hemingway

2010

Stokes S. Baker

Beverly J. Brown

Christopher H. Haufler

Claire A. Hemingway

2011

Stokes S. Baker

Beverly J. Brown

Christopher H. Haufler

Claire A. Hemingway

2012

Stokes S. Baker

Beverly J. Brown

Susan R. Singer

Claire A. Hemingway

2013

Carina Anttila-Suare

J.P. (Phil) Gibson

Marshall D. Sundberg

Catrina T. Adams

2014

Carina Anttila-Suare

J.P. (Phil) Gibson

Marshall D. Sundberg

Catrina T. Adams

2015

Carina Anttila-Suare

J.P. (Phil) Gibson

Allison J. Miller

Catrina T. Adams

PSB 62 (3) 2016

135

the annual AIBS meetings from the 1950s

through 1999, the last big AIBS-coordinated

societies meeting. In 2000, BSA was the last

of the charter societies to separate its annual

meeting from AIBS and set off on its own.

Increased activity during the past two de-

cades reflects an emphasis on implementing

the goals and actions enumerated in Botany

for the Next Millennium (Botanical Society of

America, 1995). Notably, these included im-

plementation of an Education Forum preced-

ing the annual meeting and implementation

of the PlantingScience program. The follow-

ing account is organized around the three pe-

riods of educational activities outlined above:

two periods of interaction between AIBS and

BSA, first through the Commission on Un-

dergraduate Education in the Biological Sci-

ences (CUEBS) and later through the AIBS

Education Committee, and recently through

implementation of the recommendations of

Botany for the Next Millennium.

AIBS: The CUEBS Years

Both AIBS and BSA benefitted from early

NSF funding of educational activities. Notable

for BSA were the Summer Science Institutes

(Sundberg, 2014). These programs continued

into the 1960s with institutes at the Univer-

sity of North Carolina (UNC; 1960, 1962,

1963, and 1969), Washington State Universi-

ty (1961), Michigan State University (1965),

University of Massachusetts (1966), and Uni-

versity of Vermont (1968). Because of the In-

ternational Botanical Congress in 1964, held

in Edinburgh, there was no institute planned

for that year, but instead, UNC hosted a spe-

cial smaller education conference. There is no

record of a 1967 Institute (Council Minutes,

1960-1989). Although the institutes were the

only NSF-supported activities sponsored by

the BSA, members of the Education Commit-

tee actively represented the Society in broader

activities, particularly with AIBS.

In 1960, the National Association of Biolo-

gy teachers proposed that the BSA formally

take over one issue of The American Biology

Teacher (ABT) per year for botanical articles.

Victor Greulach (Fig. 2), then in his fifth and

final year as Education Committee Chair, re-

ported that the Committee recommended the

Society simply encourage members to submit

articles to ABT rather than sponsor a full is-

sue. The Committee also recommended that

the Society not produce and distribute leaflets

to schools, but instead contribute to Turtox

News, an ongoing commercial publication. It

also recommended that BSA participate in an

AIBS conference for biologists and journalists

to promote better dissemination of botanical

information to the general public. This was

seen as particularly important because the ed-

ucational materials so far produced by AIBS

(a film series distributed by McGraw-Hill)

were “deficient in botanical quantity, quality, and

accuracy” (Council Minutes, 1960; AIBS, 1972).

Figure 2. Victor Greulach, first Executive Di-

rector of CUEBS and former BSA Education

Committee Chairman. (CUEBS photo)

PSB 62 (3) 2016

136

The following year Greulach was replaced as

chair by Harriett Creighton (Fig. 3), resulting

in a whirlwind of new activity by the Commit-

tee. A survey was sent to the membership to

get ideas about teaching models that could be

produced or approved by the Society, in col-

laboration with AIBS and the Biological Sci-

ence Curriculum Study (BSCS), to facilitate

high school botanical instruction. The Com-

mittee also proposed to the Council that BSA,

through AIBS, apply to the NSF for a grant to

study the botanical content of high school and

college curricula. Collaboration with BSCS

was seen as particularly important to obtain

buy-in from high schools. The Committee re-

versed itself from the previous year and rec-

ommended sponsoring one issue of ABT per

year—a motion that was approved. The Board

also approved a proposal to co-sponsor, with

Section G (Botanical Sciences), a symposium

at the forthcoming AAAS meeting in hopes

that the proceedings would be published in

the AAAS Frontiers of Plant Biology series.

In response to the Committee’s recommenda-

tion, the Society established a Committee on

Institutes, to plan and arrange for pre-meeting

educational conferences and to continue the

Summer Institutes. A final motion, passed by

the Council, was to award certificates to high

school students who won awards for botanical

projects.

From 1961 through 1965, BSA did co-spon-

sor an annual AAAS symposium titled “Plant

Biology Today: Advances and Challenges,”

whose purpose was to provide useful up-

dates on botanical research for college profes-

sors along the lines of the summer institutes

(AAAS, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965). Full

proceedings were not published, but papers

from the first three symposia were collect-

ed by Wadsworth in a small volume meant

to supplement textbooks in advanced high

school and college courses (Jensen and Ka-

valjian, 1963, 1966). The first edition included

papers by five of the six 1961 presenters: James

Bonner, molecular biology; William Jensen,

the problem of cell development in plants;

Lawrence Bogorad, photosynthesis; Beatrice

Sweeney, the measurement of time in plants;

and Frank Salisbury, translocation: the move-

ment of dissolved substances in plants (Jen-

sen and Kavaljian, 1963). To these the second

edition added papers by Warren H. Wagner,

Jr, modern research on evolution in the ferns;

Bruce Bonner, phytochrome and the red, far-

red system, from the 1962 symposium; and

Ralph Alston and Billy Turner, biochemical

methods in systematic; Henry Andrews, some

recent developments in our understanding of

pteridophyte and early gymnosperm evolu-

tion; Walter D. Bonner, Jr., electron transport

systems in plants; and Vernon Ahmadjian,

cultural and physiological aspects of the li-

chen symbiosis, from the 1963 session (Jensen

and Kavaljian, 1966).

The Teaching Section also amended their by-

laws in 1963. There is no record of the orig-

Figure 3. Harriet Creighton, President of

BSA, Chairwoman of BSA Education Com-

mittee, and CUEBS panelist (liberal education

[non-majors], AIBS Committee on Education,

and the NSF Committee on Teaching Biology).

(Photo complements of Lee Kass.)

PSB 62 (3) 2016

137

Commissioners

Henry Koffler, Vice-Chairman, 1966-7. Chairman 1967-69 (Purdue); C. Ritchie Bell (North Carolina); Winslow R. Briggs

(Harvard); Martin D. Brown (Fullerton Junior College); Lincoln Constance* (Berkeley); Lafayette Frederick (Atlanta University);

Arthur W. Galston* (Yale); Victor A. Greulach (North Carolina); Adolph Hecht (Washington State); James H.M. Henderson (Tus-

kegee Institute); Robert W. Long (South Florida); Leonard Machlis (Berkeley); Aubrey W. Naylor (Duke); G. Ledyard Stebbins*

(Davis); and Carl P. Swanson (UMass).

Executive Staff

Director: Victor A. Greulach, 1964-65 (North Carolina)

Staff Biologists: Donald S. Dean (Baldwin Wallace College); N. Jean Enochs (Michigan State); Franklin F. Flint (Randolph-Macon

Woman’s College); Leroy G. Kavaljian (Sacramento State).

Panels

Undergraduate Major Curricula: Winslow R. Briggs (Stanford); Henry Koffler (Purdue)

Biology in a Liberal Education: Harriet B. Creighton* (Wellesley); Charles Heimsch* (Miami University); Carl P. Swanson (Johns

Hopkins).

Biology in the Two-year College: Martin D. Brown, 2nd Chairman (Fullerton Junior College).

Instructional Materials and Methods: Samuel N. Postlethwait (Purdue); Clarence Taft (Ohio State).

Biological Facilities: C. Ritchie Bell, Chairman (North Carolina); Richard D. McKinsey (Virginia).

College Instructional Personnel: Lewis E. Anderson (Duke); Sanford S. Tepfer (Oregon).

Preparation of Biology Teachers: Addison E. Lee (Texas); Edward M. Palmquist (Missouri).

Preprofessional Training for the Agricultural Sciences: J.R. Shay (Purdue).

Interdisciplinary Cooperation: Aubrey W. Naylor, Chairman (Duke); Charles C. Bowen (Iowa State); Henry Koffler (Purdue).

Table 2. BSA Members who were Officers and Committee Members of CUEBS.

inal section bylaws, but the 1963 revision

stipulated that the primary objective of the

section was “to arrange a suitable program

on botanical teaching in connection with the

annual meetings of the Botanical Society of

America, Inc.” Other objectives were to en-

courage sound teaching of botany, to explore

new methods of teaching, to assist in dissem-

inating information about botanical teaching,

and to cooperate with other organizations to

achieve these aims. Officers should be elected

at the annual business meeting and candidates

should be presented by a nominating commit-

tee of two, appointed by the section chair. The

chair and vice-chair were to serve one year

with the vice-chair automatically assuming

the chairmanship the following year. The sec-

retary treasurer had a three-year term, and the

representative to the Editorial Board of the

American Journal of Botany served a five-year

term (Council Minutes, 1964).

Another successful initiative was the joint pro-

gram with AIBS and BSCS to develop botani-

cal teaching charts and models. The first three

models were in production by A.J. Nystrom

and Co in 1963, and by 1968 eight models of

plant structure and 12 teaching charts (with

transparencies for overhead projection) were

available. Each model was accompanied by a

small booklet, equivalent to a short textbook

chapter, explaining the structure illustrated

(Kass, 2005).

Some of Creighton’s initiatives were less suc-

cessful. The summer institutes did contin-

ue through 1969, and a series of educational

pre-conferences were held in 1968, 1970, and

1973—but neither was sustainable. The high

school certificate program got lost in admin-

istrative details (designing an appropriate cer-

tificate and “finding” the official BSA seal to

use on them) and was ultimately discontinued

in 1965 without a single awardee (Council

Minutes, 1961-1965).

Creighton resigned as Education Commit-

tee chair in 1962 (to be replaced by Adolph

PSB 62 (3) 2016

138

Hecht), the same year in which CUEBS was

established under the auspices of AIBS and

Victor Greulach was appointed the first execu-

tive director (CUEBS, 1965). The first CUEBS

conference in February, 1964 was limited to

representatives of eight universities that had

already initiated new courses and curricula,

but the second conference, in May, included a

much broader representation from 50 colleges

and universities and included Hecht and Sam-

uel Postlethwait (Fig. 4) from BSA. CUEBS

and BSA initiatives were closely tied for the

eight years of the Commission’s existence, and

many CUEBS officers and committee mem-

bers were drawn from BSA membership (Table 2).

As Chairman of the BSA Education Commit-

tee and the Educational Materials and Meth-

ods panel of CUEBS, Postlethwait spearhead-

ed the integration of programs at the annual

BSA meetings. In 1964 the Teaching Section

sponsored a symposium on the use of living

material in botanical teaching. Paul Vestal in-

troduced the symposium and Harriet Creigh-

ton described how a sustained study of plant

growth could provide the framework for an in-

troductory course. Harold Bold spoke on “the

neglected cryptogams,” while Howard Arnott

described “supermarket plant anatomy.” The

final paper on molecular plant taxonomy was

presented by C. Ritchie Bell (Abstracts, 1964).

The 1965 panel discussion on the progress

in the teaching of botany was co-sponsored

by the Teaching Section and NSTA. Pos-

tlethwait began with a presentation on auto-

tutorial teaching followed by a CUEBS panel

discussion, which included Victor Greulach,

Winslow Briggs, Lincoln Constance, Arthur

Galston, Aubrey Naylor, G. Ledyard Stebbins,

Carl Swanson, and Roy A. Young. Later that

afternoon, W. Gordon Whaley, William Jen-

sen, Harlan Banks, and David Anthony pre-

sented at a teaching section symposium titled

“Supplementing the living plant in the teach-

ing of botany” (Abstracts, 1965; Council Min-

utes, 1965).

In 1966, Helena Miller presided over a sym-

posium, “Basic concepts in botany—initial

college course.” It was co-sponsored by the

Teaching, Developmental, and General Sec-

tions of the BSA, the American Society of

Plant Physiologists, and the NABT. James

Bonner, G. Ledyard Stebbins, Frederick Stew-

ard, and Kenneth V. Thimann were the speak-

ers. The last three papers were subsequently

published in Bioscience (Stebbins, 1967; Stew-

ard, 1967, Thimann, 1967). These sessions

were no longer updates on the field, as in

the past, but were concerned with the place

of botany in a biology curriculum, and how

to incorporate botany into the general biol-

ogy course. The following afternoon Martin

Schein and Ted Andrews presented a panel

discussion and report on CUEBS activities.

In 1966 Postlethwait also sent out a question-

naire to the membership to gain information

on “Tachyplants”—plants with rapid enough

life cycles to be completed within one semes-

Figure 4. Samuel Postlethwait: BSA Teach-

ing Section and Education Committee

Chair, CUEBS panelist (Instructional Mate-

rials), and BSA Program Director.

PSB 62 (3) 2016

139

ter. This project was co-sponsored by the BSA

Education Committee and the CUEBS Panel

on Instructional Materials and Methods. Pos-

tlethwait and N. Jean Enochs published the

results the following year in the Plant Science

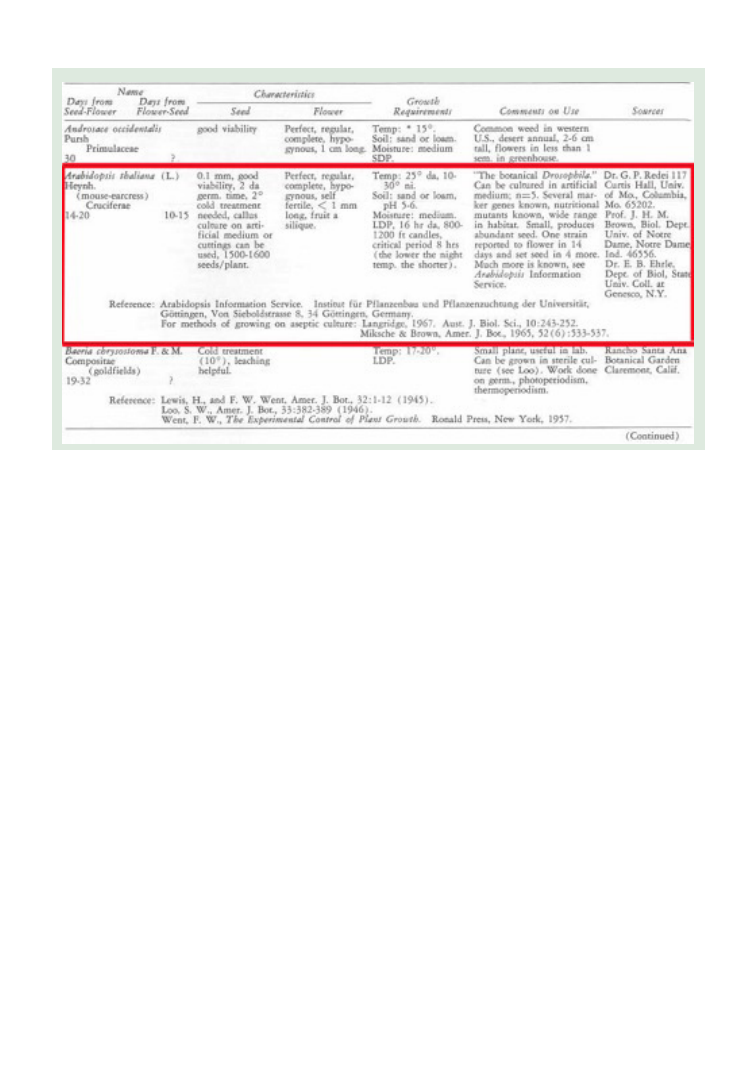

Bulletin (1967). Figure 5 is an excerpt from

that article highlighting the advantages of the

mouse-eared cress, Arabidopsis thaliana, as

a plant with great potential (Abstracts, 1966;

Council Minutes, 1966).

The 1967 annual meeting program again in-

cluded two symposia. The first, including

David Gates, Warren H. Wagner, and J. van

Overbeek, again focused on updating con-

cepts for advanced college courses. However,

the afternoon symposium, led by Postlethwait,

focused on CUEBS initiatives: pedagogy, new