IN THIS ISSUE...

SPRING 2018 VOLUME 64 NUMBER 1

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

A PUBLICATION OF THE BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA

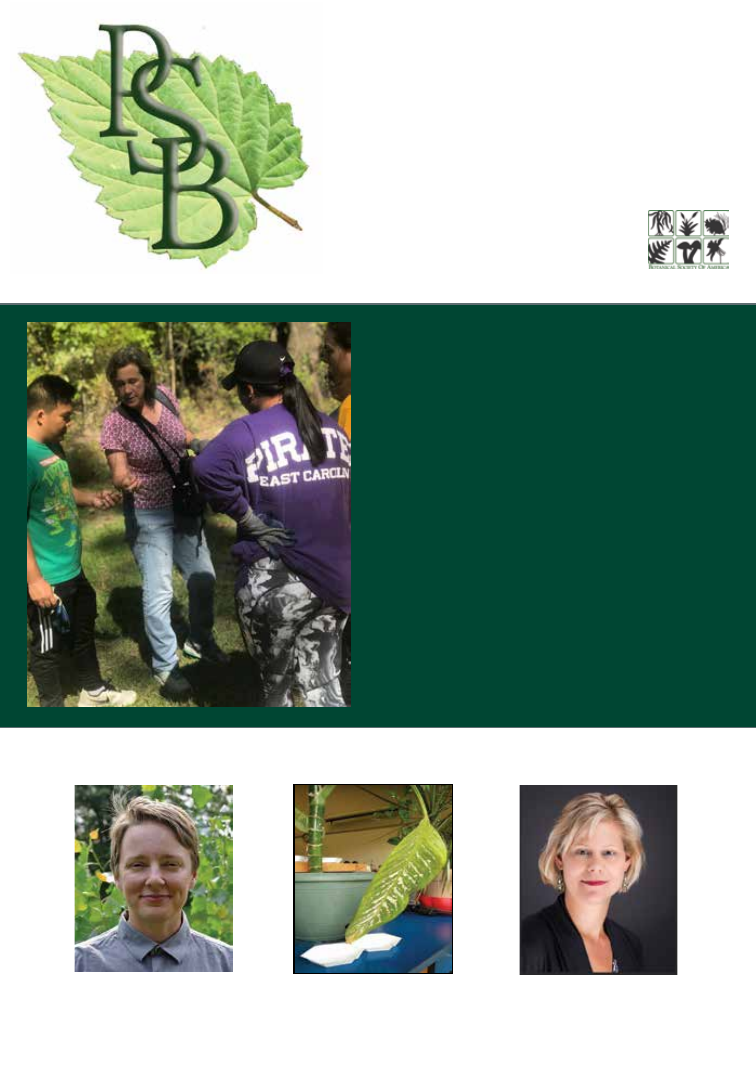

Star Project winners from the lat-

est PlantingScience session...p. 29

Kal Tuominen on humanizing

the academic science career

pipeline...p. 18

Heather Cacanindin named new

BSA Executive Director...p. 42

Combating

Plant Blindess and a

Plant Invasion through

Service-Learning

by Carol Goodwillie and

Claudia Jolls

SPRING 2018 Volume 64 Number 1

PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN

Editorial Committee

Volume 64

From the Editor

Kathryn LeCroy

(2018)

Environmental Sciences

University of Virginia

Charlottesville, VA 22904

kal8d@virginia.edu

Melanie Link-Perez

(2019)

Department of Botany

& Plant Pathology

Oregon State University

Corvallis, OR 97331

l

inkperm@oregonstate.edu

Shannon Fehlberg

(2020)

Research and Conservation

Desert Botanical Garden

Phoenix, AZ 85008

sfehlberg@dbg.org

David Tank

(2021)

Department of Biological

Sciences

University of Idaho

Moscow, ID 83844

dtank@uidaho.edu

Greetings,

I am writing this on a cold, icy day in Omaha,

but I am happily looking ahead to the summer.

Abstract submission and registration is cur-

rently open for BOTANY 2018 in July in Roch-

ester, MN. If you haven’t attended a Botany

meeting in a while (or ever), I encourage you

to think about attending this summer. You can

find information about this year’s conference at

http://2018.botanyconference.org and on page

8 of this issue. There is an exciting line-up of di-

verse special lectures and an array of colloquia,

workshops, and symposia.

I want to personally encourage graduate and

undergraduate students to attend the meeting.

I attended my first meeting just after my soph-

omore year in college and my experience sig-

nificantly contributed to my choosing to pur-

sue a career focusing on plant science. I have

since encouraged several of my undergraduates

to attend and have continually been pleased

with their experiences. There are several travel

grants to support student travel. Information

about these, as well as many other resources for

students, can be found in this issue’s Student

Section.

In this issue, we also tackle issues of diversity

and inclusion in plant science (p. 18) and pres-

ent a case study in combating plant blindness

(p. 11). Both of these address challenges that

we, as botanists, face.

I hope to see many of you in Rochester. As al-

ways, if you have an idea for a PSB article or a

news item of interest to the society, please do

not hesitate to contact

me.

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SOCIETY NEWS

Public Policy Quarterly BALA recap ................................................................................................................... 2

In Memoriam - Elizabeth Farnsworth (New England WIld Flower Society) .................................. 4

Traveling to South Korea for Fieldwork (not involving plants) ............................................................ 6

Get Ready for Botany 2018 .................................................................................................................................... 8

SPECIAL FEATURES

Combating plant blindness and a plant invasion through service-learning ............................. 11

Humanizing the academic science career pipeline: interdisciplinarity in

service to diversity and inclusion ...................................................................................................................... 18

SCIENCE EDUCATION

Education News and Notes .................................................................................................................................. 28

STUDENT SECTION

Roundup of Student Opportunities .................................................................................................................. 32

ANNOUNCEMENTS

Heather Cacanindin BSA's new Executive Director ............................................................................... 42

BSA research journals successfully move to Wiley platform ........................................................... 43

TreeTender movie .................................................................................................................................................... 44

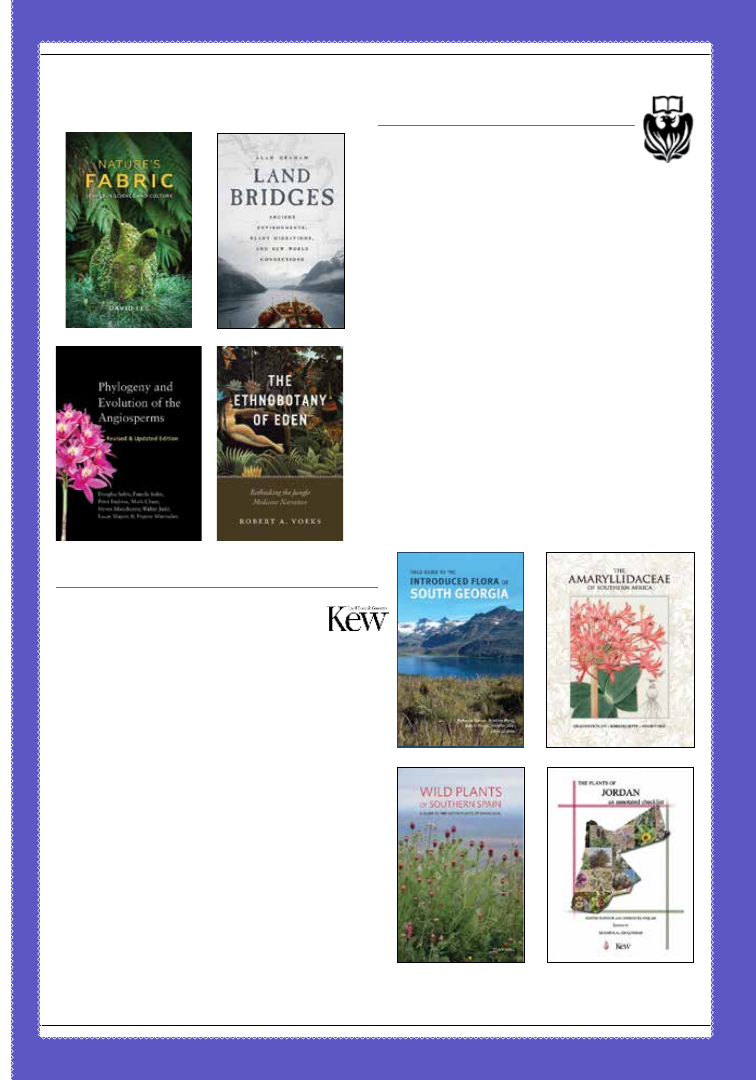

BOOK REVIEWS

Development and structure .................................................................................................................................. 45

Ecology ............................................................................................................................................................................ 47

Economic botany ....................................................................................................................................................... 51

Education ........................................................................................................................................................................ 53

History ............................................................................................................................................................................... 54

Systematics................................................................................................................................................................... 56

2

SOCIETY NEWS

Public Policy News

Last year, the ASPT Environment and Public

Policy Committee (EPPC) and the BSA Public

Policy Committee (PPC) awarded $1000 to

fund a workshop titled “Plant Conservation

and Sustainable Management by Women in

the Jaragua-Bahoruco-Enriquillo Biosphere

Reserve, Dominican Republic: Community

Workshop and Local Capacity.” These

funds—the 2017 Botany Advocacy Leadership

Award—provided the necessary compensation

for supplies for the workshop, travel, and

compensation for the teachers involved. This

annual award organized by the Environmental

and Public Policy Committees of BSA and

ASPT aims to support our members’ efforts

that contribute to shaping public policy on

issues relevant to plant sciences.

The workshop, held on August 31, 2017, in

Oviedo, Perdenales, Dominican Republic,

was a great success; participants and garden

instruction can be seen in the figures on the

following page. Jaragua-Bahoruco-Enriquillo

is the only biosphere reserve in Hispaniola

Island and is located in the southwest of the

Dominican Republic, near the boundary

with Haiti—including some of the poorest

regions of this island. However, this is a very

rich area in biodiversity and plant endemism,

many of which are valued for their medicinal

properties. All the biodiversity of the area

is threatened by human activities, mainly

deforestation for charcoal making, low-yield

cattle ranching, or subsistence agriculture.

These factors put at risk many locally endemic

species, such as Pimenta haitiensis, a medicinal

plant widely used in the country.

The first essential step in biodiversity

conservation in any threatened area is to

integrate the local communities. By working

closely with rural populations who are in

contact with the biodiversity of the reserve,

programs like this can help promote the

educational and economic development

that will alleviate poverty in the region. This

workshop promoted the conservation of

endemic and native plants in the Jaragua-

Bahoruco-Enriquillo Biosphere Reserve and

encouraged the sustainable use of native

plants by women of local

communities. Most of the

plants that were used for

planting at the garden are

endangered and rare species,

traditionally used by local

communities as sources of

fruits, as well as medicinal

and aromatic plants.

By Ingrid Jordon-Thaden (University of California Berkeley),

ASPT EPPC Chair, Krissa Skogen (Chicago Botanic Garden),

and Kal Tuominen (Metropolitan State University), BSA PPC

Co-Chairs

PSB 64 (1) 2018

3

The Botany Advocacy Leadership Award (BALA) is in its third year of supporting a project like

this. The deadline each year is the end of March, and announced in mid-April. See the BSA

and ASPT award sites (https://cms.botany.org/home/awards.html and https://aspt.net/award/#.

WphggIJG0_U, respectively) for application details.

PSB 64 (1) 2018

4

In Memoriam

Elizabeth Farnsworth

(1962-2017)

On October 27, 2017, Dr. Elizabeth Farnsworth

died unexpectedly at her home in Amherst,

Massachusetts. She was 54. For those who

knew and worked with her, who played music,

paddled, or hiked with her, who cleaned

seeds beside her while swapping stories at

the long tables at Garden in the Woods and

Nasami Farm, who took her online courses

or heard her lectures, “unexpectedly” is a vast

understatement. The words “Elizabeth” and

“died” do not belong on the same page. That

she was in her prime, radiating warmth and

vitality, a vivid picture of apple-cheeked, wild-

maned health, makes this notion profoundly

hard to accept, and bitterly unacceptable.

After all, as one can imagine her shouting in

the face of whatever stopped her heart that

day, she still had so much to do.

She already had packed a lot of achievement

into her foreshortened life, as at least one

grieving colleague observed. She was an

accomplished botanist, educator, and scientific

illustrator. At the time of her death, Elizabeth

was co-leading the New England Wild Flower

Society’s effort to conserve seeds of hundreds

of rare plant species throughout New England.

But Elizabeth’s many contributions to the

Society started more than two decades ago.

Recent members might know that she wrote,

constructed, and taught the Society’s first

set of online botany courses and wrote the

ground-breaking “State of the Plants” report.

A few years earlier, she co-led the National

Science Foundation grant for developing Go

Botany, the Society’s interactive online guide

to the entire New England flora, and then

won an additional grant from the same source

to support student research in conservation

biology. She coordinated planning for the

conservation and management of more than

100 species of rare plants. She illustrated

dozens of entries in Flora Novae Angliae by

Arthur Haines, the Society’s research botanist.

And with a grant from the Institute of

Museum and Library Services, she conducted

an assessment of seed banking and collections

practices at the Society and published a

model protocol by which to prioritize target

populations for seed collection. A natural and

passionate teacher, Elizabeth jumped in to

serve as interim education director in 2013,

arranging all the courses the Society offered.

The Society is not the only institution that

will miss her and her scholarly contributions.

When she died, Elizabeth was serving as senior

editor of the botanical journal Rhodora and

on the graduate faculties of the University of

Massachusetts Amherst and the University of

PSB 64 (1) 2018

5

Rhode Island. Before that, she also had taught

at Smith, Mount Holyoke, and Hampshire

colleges and the Conway School of Landscape

Design. As a writer, she displayed the rare

ability to address both academic peers and

novice botanists with equal clarity—and not

a whit of condescension for the latter. To date,

she had published 54 peer-reviewed scientific

journal articles and 61 invited publications

for public media. She also co-authored the

award-winning A Field Guide to the Ants of

New England, which she also illustrated; the

Connecticut River Boating Guide: Source to

Sea; and the Peterson Field Guide to the Ferns.

Her delicate, precisely rendered illustrations

also grace the pages of Natural Communities

of New Hampshire and three other books.

How, then, did she find time to deliver more

than 230 invited presentations throughout the

world, much less to sing and play guitar semi-

professionally and paddle her prized hand-

built kayak? Alas, it is too late to ask. She loved

to travel, preferably in further exploration of

the natural world, and, at various times in her

career, she conducted research on ecosystems

all over the globe, focusing on conservation,

plant physiology, mangroves, and climate

change. She served as a scientific consultant to

the United Nations, the National Park Service,

The Trustees of Reservations, the U.S. Forest

Service, the Massachusetts and Connecticut

Natural Heritage programs, and the Mount

Grace Land Conservation Trust.

Brilliance marked her early: At Brown

University, Elizabeth earned her B.A. in

environmental studies in seven semesters,

graduating with honors. She went on to study

at University of Vermont, receiving her M.S.

in field botany. While earning her Ph.D. at

Harvard University, she was awarded a Bullard

Research Fellowship and a National Science

Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship. Her

dissertation on mangrove seedlings launched

a journey to 17 countries as a Harvard

Traveling Scholar, to conduct a comparative

survey of mangroves. She was honored to be

chosen as a teaching assistant to E. O. Wilson,

with whom she shared a passion for ants.

Elizabeth, a gifted storyteller, enjoyed sharing

tales of her travels and other adventures—

about the time all the members of the Grateful

Dead crashed at the house she shared with

roommates in college, about sitting around

camp with David Attenborough in a South

American rainforest, about leeches invading

unmentionable places (which, of course, she

mentioned). Now her friends, colleagues, and

students are seeking solace by sharing our

memories and stories about her.

“She was that rare human being who was

talented in both the sciences and the arts, who

excelled in everything she did,” said Director

of Conservation Bill Brumback, the person at

the Society who has worked most closely with

Elizabeth over the years. “And she made the

world a little better for those who knew and

worked with her.”

For those who would like to honor Elizabeth’s

legacy with a donation, her family suggests sending

donations to:

• New England Wild Flower Society

(https://46858.blackbaudhosting.com/46858/

Memorial),

• Hitchcock Center for the Environment

(https://donatenow.networkforgood.org/

elizabethfarnsworth),

• or any other conservation organization of the

donor’s choice.

(Reprinted with permission from the

New England Wild Flower Society: http://

newenglandwild.org/elizabeth-farnsworth.

html.)

PSB 64 (1) 2018

6

Fieldwork, in my mind, conjures up images

of long journeys to interesting places,

often-inclement weather, sleeping in tents,

exhaustion at the end of the day, and the

exciting possibilities of discovering something

new. Fieldwork for an editor is similar in some

ways but is usually a little less outdoorsy. In

late November of 2017 I went “into the field”

to meet with editors halfway around the world

to talk about publishing: specifically, about

what a managing editor of a scientific journal

does. The destination: Seoul, South Korea.

The email invitation arrived in mid August,

soon after I returned from the International

Botanical Congress in Shenzhen, China, which

was a fascinating experience (and my first

trip to Asia). The Korean Council of Science

Editors (KCSE) and Korean Federation of

Science and Technology Societies (KOFST)

are two organizations headquartered in Seoul,

which are allied with the Council of Science

Editors in the States. They had invited my

friend and colleague Patty Baskin, of the

American Academy of Neurology, to present

on aspects of publication management, and

Traveling to South Korea for

Fieldwork (not involving plants)

By Amy McPherson

Director of Publications

of Managing Editor

Botanical Society of

America

ORCID 0000-0001-7904-242X

she invited me to accompany her. In Korea,

many journal editors work on their own, but

there is great interest in setting up editorial

offices with managing editors or assistants.

I was thrilled to be invited and accepted

straightaway. And then a bit of anxiety set in.

News headlines were sounding the alarms of

rising tensions between the leaders of the U.S.

and North Korea throughout the fall months.

Would a trip to South Korea be advisable in

these uncertain times?

I planned my presentations, purchased

travel insurance (just in case), and left on an

airplane on November 28, 2017, bound first

for Atlanta, then on to Seoul. Despite my

concerns, and the uncertainty of the political

climate, it was an interesting, productive, and

altogether enjoyable trip. [Note to self: To

relax while traveling, turn off news alerts on

your cell phone. It does not help to know that

impressive intercontinental ballistic missile

tests are taking place close to where you have

just landed.]

My colleague and I took a long journey to an

interesting place, with somewhat inclement

weather, and were exhausted at the end of the

day. The flight from Atlanta to Seoul is over

15 hours long, and the ride from the airport

to our hotel in the Gangnam District took

another hour. Seoul is a vibrant, fast-moving,

high-tech city of over 10 million people

(over 25 million if you include the sprawling

metropolitan area, according to the World

Population Review). The Gangnam District

is a hip, upscale, modern area that attracts

PSB 64 (1) 2018

7

young people by the thousands on a Friday

night. The metro was beyond crowded. The

two days of meetings were cold (–3° C), and

we experienced one of the first snows of the

winter. The long flight, the intense days of

meetings, and the considerable jet lag led to

exhaustion at the end of the day, and that odd

limbo when your body and mind don’t know

whether to be awake or asleep.

Even though it was a very short trip, there

was much to share and discover. I presented

on journal metrics and spoke on the duties

of a managing editor, which are essentially

to oversee the smooth day-to-day running

of the editorial office, and everything that

comes with that. We manage the publication

process, working with authors, reviewers, and

editors from before submission through post-

publication; we copy edit manuscripts and

handle production; we work with vendors

and publishers; we keep up to date on all the

various trends and concerns in the publishing

arena; we handle ethics, copyright, plagiarism,

permissions, instructions for authors, and

requests for information; we seek out special

papers and facilitate special, themed issues; we

work on our publications and for the societies

we serve; we promote articles, authors, and

society members via social media; and we do

it all in a professional manner.

What I discovered was that our Korean

counterparts were handling many of these

tasks themselves and were also maintaining

full-time positions in their research areas.

They are concerned with the same issues we

are, including journal Impact Factors and

other evaluation metrics (but with emphasis

on IFs); writing peer reviews for academic

journals; establishing and following journal

style; distinguishing between predatory and

non-predatory Open Access journals; and

managing scientific investigations involving

ethics, copyright, and plagiarism (and

beyond). They are also deeply concerned with

their publications programs and are looking

to compete on a much more international

scale—and I have no doubt they are going to

succeed.

Outside of the formal lectures and

presentations, we spent time drinking

coffee and eating delicious food (stunningly

delicious, fresh seafood!) and talking about

publications, yes, and also about our cultures

and current tensions between and among

North and South Korea and the United

States. It was fascinating to discuss the state

of the world in which the concerns were real

for all of us—immediate political concerns,

but also the realities of climate change, the

importance of education, and the necessity of

global solutions to some of the problems we

all face. I discovered during that trip hope for

a better way forward. I left Korea with new

friends and colleagues: we have a lot to learn

from each other, and I look forward to future

collaborations.

PSB 64 (1) 2018

8

Are you ready ?

Don't miss the best scientific conference of the summer!

Join us in the vibrant city of Rochester, Minnesota!

Timely Symposia and Colloquia

Infomative Workshops

Spectacular Field Trips

Over 950 Oral and Poster presentations

Exhibits

Networking Events

Something for everyone!

PSB 64 (1) 2018

9

Featured Speakers

Plenary Lecturer

Walter Judd

Flora of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-Earth

Regional Botany Special

Lecture

George Weiblen

Annals of Botany

Lecture

Elena Conti

Kaplan Memorial

Lecture

Toby Kellogg

.

Incoming BSA President

Lecture

Andi Wolfe

Pelton Award

Lecture

Neelima Sinha

Emerging Leader Lecture

Benjamin Blackman

PSB 64 (1) 2018

10

Enhance your Conference experience

Sign up for a field trip and experience the

Botany of the Rochester area!

For complete information, descriptions, and fees, go to:

http://2018.botanyconference.org/field-trips.html

New this year!

Botanical Society of America will reimbuse any student member

up to $100.00 for field trip fees. Sign up early!

Reimbursements are first-come, first-served!

Information on the conference website

Friday Trips

• Join the Fern Foray - Do the overnight adventure or just come

for the day!

Saturday Trips

• Explore the Big Woods and go Kayaking - Check out the video

on the site!

• Visit the Cedar Creek EcosystemScience Reserve

• Collect and identify Sedges at the Whitewater Wildlife

Management Center

• Hike the Weaver Dunes Prairie - and then canoe the marsh

and look for the American Lotus!

• Check out the Glacial Relics and the fire-dependent Plant

communities

Sunday Trips

• Hike through Whitewater State Park

• Visit Mystery Cave State Park

• Walk through the Minnesota Landsape Arboretum and then

Prince's private estate - Paisley Park

• Discover the New Bell Museum, the MIN Herbarium and Surly

Brewing Company

Post-Conference Thursday Trips

• See the Karst bedrock and tour the Whitewater Valley

• Another chance to go Kayaking on the Cannon River

11

Abstract

Inspired by a critical deficit in field botany

experiences in higher education, we developed

an undergraduate service-learning program

in invasive plant biology that introduces

students to botany while they contribute

to solving a local ecological problem. Since

2014, undergraduate biology students at East

Carolina University (ECU) have worked with

the city recreation and parks department

to control an invasion of sericea lespedeza

(Lespedeza cuneata) along a local greenway.

Service-learning is incorporated into sections

of an existing lecture course in plant biology,

with invasive plant removal accomplished in

sessions outside of assigned class time. During

fieldwork, observations of plant structures

and native plants reinforce lecture material on

plant biology. In turn, invasive plant biology

is used as a theme throughout lectures to

SPECIAL FEATURES

Combating Plant Blindness

and a Plant Invasion Through

Service-Learning

illustrate concepts in plant physiology and

reproduction. Our efforts appear to be have

been effective in slowing the invasion of

lespedeza and inspiring students to explore

botany and environmental issues.

“P

lant blindness” is a confirmed bias,

with significant implications for con-

servation and management (Wandersee and

Schussler, 2001; Balding and Williams, 2016).

This bias against plants is further exacerbat-

ed by limited appreciation for and experi-

ence with the out-of-doors, argued to result

in a range of negative consequences, the so-

called “nature-deficit disorder” (Louv, 2005).

Outdoor settings are preferable for teaching

species identification and concepts in ecolo-

gy (Randler, 2008; Stagg and Donkin, 2013).

Direct field experience also has potential to

help promote what Balding and Williams

(2016) termed as “empathy” with plants for

By Carol Goodwillie

Department of Biology, East Carolina University,

Greenville, NC; e-mail: goodwilliec@ecu.edu

Claudia L. Jolls

Department of Biology, East Carolina University,

Greenville, NC

;

e-mail: jollsc@ecu.edu

Received for publication 27 November 2017; revision accepted 5 January 2018

PSB 64 (1) 2018

12

greater botanical literacy. Yet biology pro-

grams worldwide place increasing focus on

molecular biology, often at the expense of

organism- or species-level knowledge and

field-based approaches, particularly in bota-

ny (Jacquemart et al., 2016). Inspired by this

critical deficit, we initiated an undergraduate

service-learning program in invasive plant

biology to introduce students to field botany

and simultaneously engage them in solving an

ecological problem in our local community.

Service-learning involves students in

experiential education to combine service

activities with reflective assignments (Eyler,

2002). This method contributes to the

community and cultivates civic responsibility

“through active participation and thoughtfully

organized service” (US National and

Community Service Acts of 1990; Jacoby,

1996). The concept of “community service” has

been extended to ecological communities and

their interface with humans, and it has been

proposed as an approach to environmental

education (Clayton, 2000). “Research service-

learning” engages students, faculty, and

the public in partnerships to ask research

questions relevant to their community (e.g.,

environmental issues related to invasion

biology) (Reynolds and Loman, 2013).

Invasive species management is an obvious

focus for service-learning. Non-native invasives

are responsible for losses of biodiversity,

other negative ecological consequences, some

human health threats, and economic damages

estimated in the billions of dollars (Pimental

et al., 2005). Invasive plants, as primary

producers, can be particularly damaging as

threats to habitats, native species, crop yields,

fire regimes, interactions, and associated

ecosystem services (e.g., pollination). Control

of plant invasions is challenging; yet in some

cases, simple manual removal can be an

effective solution (Kettenring and Adams,

2011) requiring only a willing workforce. The

energy and enthusiasm of undergraduates can

be harnessed for this effort.

A SERVICE-LEARNING

PROJECT IN INVASIVE

PLANT BIOLOGY

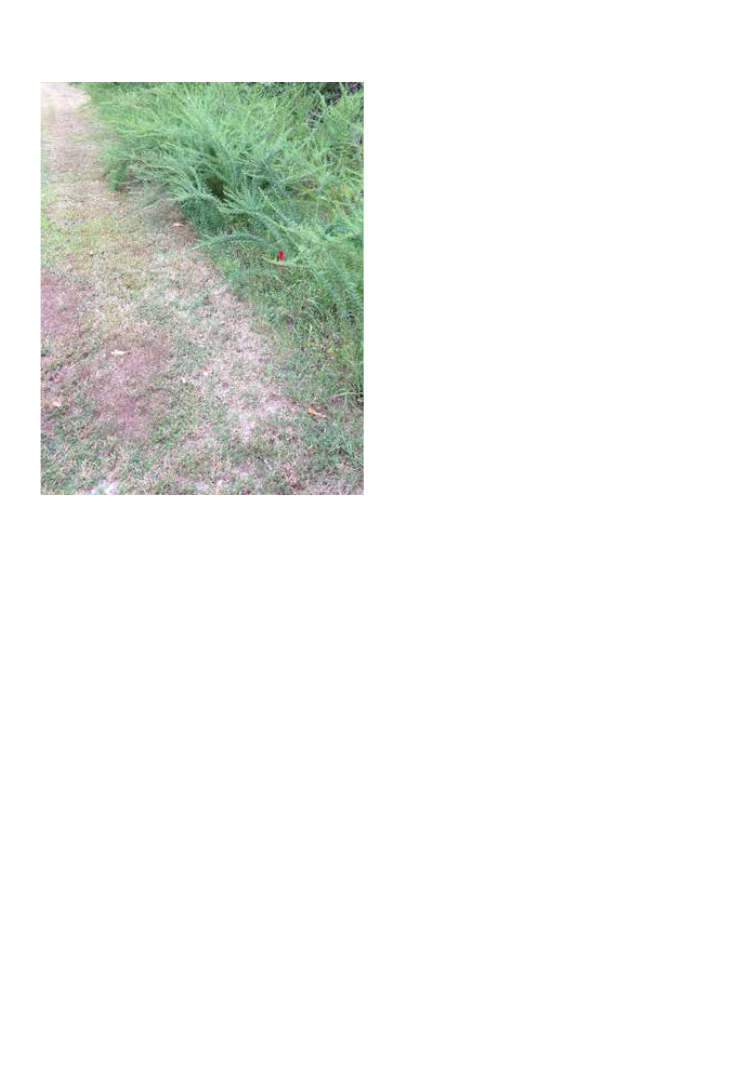

The problem

Soon after a 2.5-mile greenway was established

in Greenville, NC, it was invaded by sericea

lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata (Dum. Cours.)

G. Don). Sericea, a semi-woody forb in the

pea family, was introduced from China to

North Carolina in 1896 for erosion control and

forage (Ohlenbusch et al., 2001). The species

grows aggressively in the introduced range

and poses increasing threats to grasslands

and other natural areas, where it outcompetes

native species (Quick et al., 2016). The sericea

invasion along the Greenville greenway was

evident soon after the trail was constructed

in 2011; we suspect that seeds were present

in sand that was brought in for fill during

construction of the paved trail. By 2014, dense

patches of sericea could be seen along the

trail (Fig. 1) and the invasion appeared to be

expanding rapidly.

Service as a solution

A service-learning program was created to

involve students at East Carolina University

(ECU) in efforts to stem the sericea invasion.

Service-learning activities are integrated into

sections of a lecture course in plant biology

that we previously developed. Offered as a

junior-level elective for biology and science

education majors, the course covers plant

PSB 64 (1) 2018

13

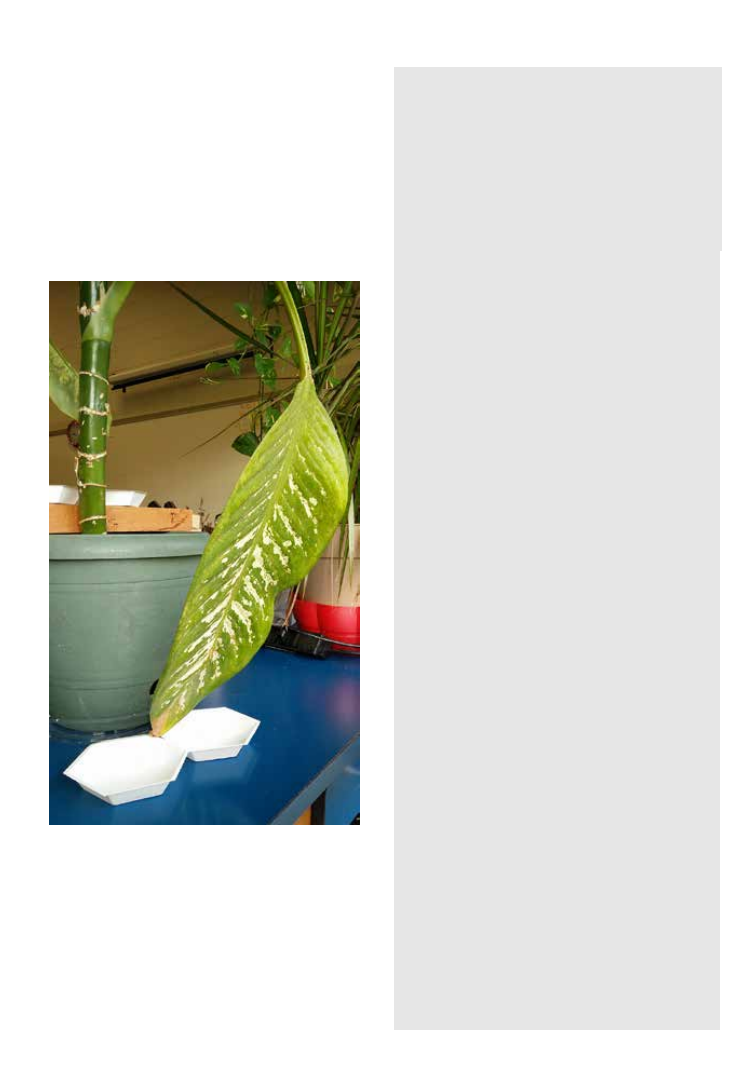

Figure 1. Three years after construction of the

greenway, dense populations of sericea lespede-

za were present in some areas.

structure, function, and diversity, including

physiology, metabolism, reproduction, genet-

ics, evolution, ecology, and human use. Since

2014, students in service-learning sections

of the course have been working in collabo-

ration with the City of Greenville Recreation

and Parks Department to control the inva-

sion of sericea along a greenway located just

a mile from the ECU main campus. During

field sessions, students work in teams to re-

move sericea plants by simple manual pulling

(Fig. 2). Although extracting the entire root

system is often difficult, removing at least the

woody caudex is relatively easy and prevents

the formation of multiple branches in the fol-

lowing year. To maximize our success in man-

aging the invasion, we supplement removal

efforts with herbicide treatment when neces-

sary. Each year we have identified a few small

patches (2-8 m

2

in size) where the plants are

too large or densities too high to make manu-

al removal feasible. The Greenville Recreation

and Parks crew applies glyphosate to these.

Service fieldwork is accomplished outside of

class time, and students are required to attend

at least two 3-hour sessions. Multiple ses-

sions are scheduled throughout August and

September, often in late afternoons or week-

ends, to ensure that all students can partici-

pate. Field time is compensated by a canceled

lecture period. Importantly, all plant removal

and herbicide application is done at the start

of the fall semester before sericea lespedeza

seeds mature and are dispersed.

Removal of plants is complemented by data

collection. One student per team serves as a

scribe in each session, recording the number

of plants removed. Because we attempt to

remove all sericea plants present, these data

serve as a record of changes in population

size throughout our project. The counts also

motivate students to work harder, as teams

often compete informally to see who can

remove the most plants.

How service contributes to learning

Service-learning as a pedagogy is built on

the idea that service can provide motivation

and context for classroom learning; in turn,

content learned in the classroom makes

the service component a deeper and more

meaningful experience (Jacoby, 1996; Eyler,

2002). We use this interplay of field and

classroom experiences in our program. During

field sessions, removal work is interrupted

intermittently to illustrate terminology and

concepts learned during lectures using sericea

and other plant species along the trail (Fig.

3). Inspection of nitrogen-fixing root nodules

on sericea plants reinforces class material on

plant nutrients and mutualisms. Lateral buds

visible on the sericea caudex prompt

PSB 64 (1) 2018

14

Figure 2. Pulling can remove sericea roots as

well as stem and caudex, as demonstrated by

this undergraduate student.

discussions of plant anatomy and perenniality.

Other species along the greenway provide

great opportunities for exploration of plant

structure and function. Students inspect

doubly-compound leaves (mimosa) and

tendrils (muscadine grape). They are asked

to think about why bark peels (river birch),

how epiphytes survive (Spanish moss), why

a parasitic plant is not green (dodder), and

what might be the benefits of seed dispersal

mechanisms (jumpseed).

During traditional classroom lectures,

invasive plants are integrated as a theme

throughout the course. During the evolution

and diversity section of the course, students

are introduced to angiosperm plant families

that contain many invasive members and even

examples of invasive mosses and ferns. We ask

students to apply and test their knowledge of

basic plant biology as they consider which

species become invasive and how invasive

species spread. The primary literature is

rich with studies on the physiological and

ecological properties of invasive plants. For

example, studies compare the invasiveness of

species with different breeding systems (e.g.,

Hao et al., 2011) and consider the role of C4

vs. C3 photosynthesis (Martin et al., 2014) or

mutualistic associations (e.g., Hu et al., 2014)

in plant invasions. These studies are presented

as capstones to lectures on each topic, with

in-class group activities that ask students to

interpret and discuss the results shown in

published graphs.

Figure 3. Field sessions are interrupted occa-

sionally to observe and explore plant structures.

PSB 64 (1) 2018

15

PROJECT OUTCOMES

Getting a handle on the invasion

Our cumulative data suggest that we are

making progress in controlling sericea

along the greenway. During the three years

of the project, counts of stems pulled by

students have declined from 6,932 in 2015

to 3,952 in 2017—a 43% reduction. The

removal data give us only a rough estimate

of the effectiveness of our efforts. Students

are somewhat inconsistent in how they

report data; multi-stemmed individuals are

occasionally counted as more than one plant.

More importantly, because our primary goal

was to manage the invasion rather than to

quantify the results of our work, we have

not retained an untreated control area for

comparison. Observations of sericea at nearby

sites suggest that, without control efforts, the

invasion would have advanced during these

three years beyond the point at which manual

removal was feasible. Moreover, demographic

modeling of sericea lespedeza predicts that

unmanaged populations can increase by

more than 20-fold per year (Schutzenhofer

et al., 2009). Despite the limitations of our

quantitative data, documenting our results is

an important motivator for students. Students

are particularly engaged in their contribution

to a longer-term dataset. In light of the

insurmountable environmental problems we

face, seeing that small efforts can have real

positive effects may be the most important

lesson that students learn.

Stealth Botany!

The course lends itself to a lecture-plus-lab

format, but we were concerned that requiring

a 3-hour lab each week would whittle our

clientele down to a small group of students

already committed to field biology. To reach

a broader group, we offer it instead as a

lecture course with required service fieldwork

done outside of class, at times arranged to

accommodate student schedules. More than

100 undergraduate students have participated

since 2015, a diverse group heading for

careers in health care, science education,

and many other disciplines. In return for the

inconvenience of leading multiple sessions to

work around students’ complicated schedules,

we have had the satisfaction of seeing pre-med

and molecular biology students get excited

about native plants and enjoy themselves in

the natural world. Hearing of our approach,

fellow plant biologist Paulette Bierzychudek

offered, “Aha, a stealth botany course!”

Indeed, the observations integrated into plant

removal work appear to be powerful learning

opportunities. Students are not required

to memorize natural history information

presented in the field and rarely take notes

during these sessions. Yet they often recount

their observations of the native plants in

accurate detail in the reflection papers they

write on their service experiences. To be

sure, we are lucky to have some especially

fascinating and charismatic plants at our

site (baldcypress, dodder, resurrection fern,

Spanish moss). We argue, though, that most

plants are quite good at communicating their

own magic; our job is mostly to get students

outside to look at them.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that our

program has broader impacts on student

interest and attitudes as well. In both verbal

and written comments, students frequently

express their new awareness of the problems

posed by invasive species and the satisfaction

they feel about “making a difference.” We have

seen students go on to other plant courses in

the curriculum, suggesting that the program

instills interest in botany. Students also have

PSB 64 (1) 2018

16

moved on to research work in faculty labs and

internships in science education outreach.

WHERE TO FROM HERE?

With the project now in place, we are

exploring opportunities for expansion. The

current anecdotal, qualitative data can be

supplemented with more formal course

evaluation. The plant biology course is

offered with and without the service-learning

component in alternate semesters, and we

have an opportunity to design a controlled

study to assess its pedagogical effectiveness.

Questionnaires to track learning outcomes

or evaluate targeted aspects of the course

can be developed with the expertise of other

colleagues in social science or education to

promote trans-disciplinary collaboration

among faculty. While our experiences to date

suggest positive student outcomes, rigorous

assessment will provide greater insight

into how service-learning in invasive plant

management affects student attitudes about

plants, conservation and civic engagement

and mastery of basic concepts in plant biology.

We are also working to expand our engagement

with community partners. Students often

express a desire to educate and involve the

public in their efforts. These discussions

led to a project by the 2016 class to design

educational signage that is now installed along

the greenway, a further collaboration with

Greenville Recreation and Parks Department

and a non-profit community organization. In

future semesters, we will explore the possibility

of students leading teams of community

volunteers to remove plants. We are fortunate

to have supportive city resource managers and

university Ground Services staff. The invasive

plant project has complemented campus

wetland restoration, University Tree Campus

USA initiative, and a Bayer CropScience Feed

A Bee Program project to use native plants in

landscaping to promote pollinator forage and

habitat.

Successful long-term management of invasive

species often involves restoration of natives in

addition to removal efforts (Kettenring and

Adams, 2011), and we plan to use this approach

in our project. A promising observation from

the 2017 season is that native plant species

(largely Symphyotrichum dumosum (L.) G.L.

Nesom and Eupatorium semiserratum DC.)

are beginning to colonize areas where sericea

lespedeza has been removed. In a pilot study

this year, we are supplementing natural

colonization by seeding open areas with native

plants found on the trail. Long-term data can

be collected on this process as well, to gauge

the effectiveness of the strategy.

Service-learning programs in invasive plant

management can be readily implemented at

other institutions. The good and bad news is

that most school campuses (K-12 and college)

have adjacent properties with plenty of

invasive plants and potential for restoration.

The program requires little financial support

and can build valuable relationships with

the community and city partners. Service-

learning using invasive plants has enabled our

students to overcome their plant blindness,

gain awareness of a critical environmental

problem, and recognize their own power to

solve problems and to contribute to something

larger and longer lasting than themselves.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Fenton, E. D. Foy, C. Horrigan,

and F. Livesay at City of Greenville Recreation

and Parks Department, J. McKinnon, T.

Abernethy, the ECU Center for Leadership

and Civic Engagement, the Dominion

PSB 64 (1) 2018

17

Foundation, Bayer Crop Science Feed A Bee

Program, and more than 100 undergraduate

participants for their contributions and

support of the project.

LITERATURE CITED

Balding, M., and K. J. H. Willliams. 2016. Plant blind-

ness and the implications for plant conservation. Con-

servation Biology 30: 1192–1199.

Clayton, P. H. 2000. Environmental education and ser-

vice-learning. On the Horizon 8: 8–11.

Eyler, J. 2002. Reflection: linking service and learn-

ing—linking students and communities. Journal of So-

cial Issues 58: 517–534.

Hao, J. H., S. Qiang, T. Chrobock, M. van Kleunen,

and Q. Q. Liu. 2011. A test of Baker’s Law: breeding

systems of invasion species of Asteraceae in China. Bi-

ological Invasions 13: 571–580.

Hu, L., R. R. Busby, D. L. Gebhart, and A. C. Yannarell.

2014. Invasive Lespedeza cuneata and native Lespe-

deza virginica experience asymmetrical benefits from

rhizobial symbionts. Plant and Soil 384: 315–325.

Jacoby, B. 1996. Service-learning in higher education:

Concepts and practices. Jossey-Bass Publishers, San

Francisco, CA.

Jacquemart, A-L., P. Lhoir, F. Binard, and C. Des-

camps. 2016. An interactive multimedia dichotomous

key for teaching plant identification. Journal of Biolog-

ical Education 50: 442–451.

Kettenring, K. M., and C. R. Adams. 2011. Lessons

learned from invasive plant control experiments: a sys-

tematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied

Ecology 48: 970–979.

Louv, R. 2005.

Last child in the woods: saving our

children from nature-deficit disorder. Algonquin Books

of Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Martin, L. M., H. W. Polley, P. P. Daneshgar, M. A.

Harris, and B. J. Wilsey. 2014. Biodiversity, photosyn-

thetic mode, and ecosystem services differ between

native and novel ecosystems. Oecologia 175: 687–697.

Ohlenbusch, P. D., T. Bidwell, and W. H. Fink. 2001.

Sericea lespedeza: history, characteristics and identi-

fication. Kansas State University Agricultural Experi-

ment Station and Cooperative Extensive Service MF-2408.

Pimentel, D, R. Zuniga, and D. Morrison. 2005. Up-

date on the environmental and economic costs associ-

ated with alien-invasive species in the United States.

Ecological Economics 52: 273–288.

Quick, Z. I., G. R. Houseman, and I. E. Büyüktahta-

kin. 2016. Assessing wind and mammals as seed dis-

persal vectors in an invasive legume. Weed Research

57: 35–43.

Randler, C. 2008. Teaching species identification: a

prerequisite for learning biodiversity and understand-

ing ecology. Eurasian Journal of Mathematics, Sci-

ence and Technology Education 4: 223–231.

Reynolds, J. A., and M. D. Lowman. 2013. Promoting

ecoliteracy through research service-learning and citi-

zen science. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment

11: 565–566.

Schutzenhofer, M. R., T. J. Valone, and T. M. Knight.

2009. Herbivory and population dynamics of invasive

and native lespedeza. Oecologia 161: 57–66.

Stagg, B. C., and M. Donkin. 2013. Teaching botanical

identification to adults: experiences of the UK partici-

patory science project “Open Air Laboratories.” Jour-

nal of Biological Education 47: 104–110.

US National and Community Service Act of 1990.

URL: https://www.nationalservice.gov/sites/default/

files/page/Service_Act_09_11_13.pdf

Wandersee, J. J., and E. E. Schussler. 2001. Toward a

theory of plant blindness. Plant Science Bulletin 47:

2–9.

PSB 64 (1) 2018

18

Humanizing the Academic

Science Career Pipeline:

Interdisciplinarity in Service to

Diversity and Inclusion

Key Words

broadening participation; culture of science;

epistemology of science; human diversity;

institutional change; interdisciplinary

research; intersectionality

A

cademic scientists have discussed the

progressive loss of human diversity at

each STEM career stage using the metaphor

of the “leaky pipeline” (e.g., Barr et al., 2008;

Chesler et al., 2010; Miller and Wai, 2015).

Data on the underrepresentation of wom-

en, people of color, and people who experi-

ence disability in STEM degree completion

and workforce participation are updated ev-

ery two years (National Science Foundation,

2013, 2015, 2017). Women now complete a

greater proportion of graduate degrees in the

biological sciences than men (National Sci-

ence Foundation, 2017), although evidence of

overt and unconscious gender bias continues

to be documented (Moss-Racusin et al., 2012;

Clancy et al., 2014). African Americans, Lat-

in Americans, and Indigenous Americans

(Native Americans and Alaska Natives) make

up an increasing proportion of bachelor’s and

master’s degree students in the biological sci-

ences, but also leave STEM undergraduate

programs at least 60% more often than white

students (Koenig, 2009; National Science

Foundation, 2017). The proportion of PhDs

completed by members of these populations

has also stagnated, despite increasing repre-

sentation in the U.S. working-age population

(National Science Foundation, 2017).

The view of academic science as a pipeline

with differential demographic leakage hints at

underlying assumptions that have influenced

those of us seeking to broaden STEM

participation. First, the idea of a pipeline belies

a normative position that scientific career

development should be a continual linear

progression (Cohen et al., 2004). This appears

to derive partly from outdated ideas that a

professional success is achieved in a single

career, which consists of an unbroken series

of jobs with increasing responsibilities in one

field. The metaphor can thus, at minimum,

facilitate men’s access to STEM careers and

perpetuate barriers to women’s (Wonch Hill

et al., 2014; Makarova et al., 2016).

Next, the concept of a pipeline leak suggests

that the location and causes of divergence

from the normative goal can be found at

By L.K. Tuominen

Department of Natural Scienc-

es, Metropolitan State Univer-

sity, St. Paul, MN

Current Address: Department

of Biology, John Carroll Uni-

versity, University Heights, OH

e-mail: ktuominen@jcu.edu

Received for publication 6 November 2017; revision accept-

ed 16 February 2018

.

PSB 64 (1) 2018

19

specific parts of the career progression,

observed, and diagnosed through data

collection. For instance, a pipeline might

leak due to “punctures,” such as experiences

of overt bias (e.g., Ferguson Martin et al.,

2016; Clancy et al., 2017; Miner et al., 2017);

“loose connections,” such as poor mentor-

protégé matching (e.g., Buzzanell et al., 2015;

Dennehy and Dasgupta, 2017); or “high

pressure,” such as balancing research time

with caretaker responsibilities (e.g., Grunert

and Bodner, 2011; Sallee et al., 2016; Tower

and Latimer, 2016). Finally, diagnosed leaks

can be targeted so that the “plumbing” can

be repaired using different approaches for

populations facing different sorts of challenges

(e.g., Tull et al., 2012; Wilson et al., 2012). For

these interventions, the pipeline has typically

been viewed at the institutional level, whether

that institution is a university, professional

society, or government; rhetorically, a key

phrase invoked in efforts to reduce leakage is

institutional transformation (e.g., Handelsman

et al., 2007; Fox, 2008; Whittaker and

Montgomery, 2014). This troubleshooting

process also creates new opportunities for

research and publication among scientist-

plumbers who pursue this much-needed area

of study. It’s all wonderfully scientific—and

how else would we expect scientists to act?

Putting scientific training to this use is not a bad

instinct, yet we should remain concerned that

pipeline troubleshooting efforts have not been

as successful as we have hoped. Institutional

efforts can improve retention of students from

underrepresented backgrounds (e.g., Tull et

al., 2012; Wilson et al., 2012), but these do not

appear to be scaling up to the national level.

The gap in the share of STEM and non-STEM

degrees completed by underrepresented

minorities has been growing during the

past decade, indicating that these students

preferentially choose against the sciences

(National Science Foundation, 2017). Such

data suggest that academic science may be

begging the question of underrepresentation:

after studying the problem empirically and

making empirically driven interventions at

the institutional level, underrepresentation

for several groups is increasing. Why believe

that continuing the same strategy will yield

success?

NATURAL SCIENTISTS IN A

SOCIAL WORLD

Sociologists of science tell us that becoming

a scientist is partly a matter of socialization

into the culture of science (Roth, 2001;

Eames and Bell, 2005; Clark et al., 2008).

What assumptions do students make about

scientists when they view this culture from

the outside? Recent stereotyping tests show

that undergraduates still most often identify

scientists as older white men (e.g., Miele, 2014;

Schinske et al., 2015). Students generally

assume scientists are intelligent (e.g., Schinske

et al., 2015). These stereotypes have relevance

for students’ decisions. Pursuit of a science

major is related to the alignment between

students’ ideas about scientists and their

self-conceptions (e.g., Lane et al., 2012; Guy,

2013). Furthermore, many students believe

intelligence is a fixed trait; those who do tend

to avoid challenging themselves with courses

they perceive as more difficult (Dweck, 2000).

Meanwhile, new graduates with STEM degrees

gain an economic advantage as they enter the

workforce (Koc et al., 2016). From cell phones

and social media to evidence-based reporting

requirements for nonprofit funding, the

public is surrounded with, even regulated by,

the results of scientific thinking. The number

PSB 64 (1) 2018

20

of U.S. jobs requiring college-level knowledge

in science and engineering is approximately

triple the number of jobs formally categorized

within these fields (National Science Board,

2016a). Americans believe the benefits of

scientific research outweigh its harms, that

the government should fund basic research,

and that leaders of the scientific community

are more trustworthy than leaders of all

American institutions other than the military

(National Science Board, 2016b). Although it

may not always feel that way to us scientists,

the stereotypes, surveys, and the ubiquity of

science all suggest having scientific training is

a form of social privilege in American society.

This raises some questions highly relevant to

supporting diversity at every level of academic

science. How many academic biologists have

formalized knowledge about the meaning

and implications of social privilege for the

classroom? Could a lack of knowledge

or training on this topic be connected

to well-intentioned, but functionally

counterproductive, classroom or mentorship

behaviors? Could the ubiquity and social

status of the natural science paradigm itself

contribute to the challenge of supporting

human diversity in biology, perhaps through

the assumption that “scientists know best”

even outside their expertise? Could our own

scientific training potentially interfere with

our goals of supporting human diversity?

For concision, I will consider only this

last question. Good scientific training

encourages certain behavioral tendencies

while discouraging others. First, we natural

scientists are enculturated to value objectivity,

which is useful to help us avoid cognitive biases.

This focus can come at the cost of discounting

individuals’ subjective experiences. Second,

we are enculturated to focus on weight of

evidence from (increasingly) large sample

sizes. The benefit is the more accurate

inference of general principles about a target

population. The cost is discarding statistical

outliers and discounting results from small

samples, both of which may provide unique

insights. Third, a focus on general cause-

and-effect patterns allows for the creation of

interventions that can be applied at the level of

a target population. Yet knowledge of general

patterns and population-level solutions do

not necessarily provide useful insights about

how to best support a particular student who

is considering leaving science.

As an example of how the trade-offs of scientific

enculturation can manifest, consider the

implications of NSF’s demographic reporting

on participation in science (National Science

Foundation and National Center for Science

and Engineering Statistics, 2013, 2015, 2017).

National-scale data on underrepresentation by

race, gender, and disability are crucial to our

understanding of diversity in STEM. However,

the demographic categories focus mainly on large

populations. The report does not provide clear

data on individuals who transcend categories,

such as biracial, transgender, or intersex

individuals, nor is the highly heterogeneous

category of disability further disaggregated.

Other groups, such as immigrants, LGBQ

individuals, first-generation college students,

and students entering at a nontraditional

age or lower economic status, are simply not

considered. This homogenized view of who

is in the pipeline precludes the possibility

of “engineering” changes attuned to the

needs of individuals whose identities are

not represented. Most of these populations

experience marginalization in American

society at large, but scientific expectation and

financial realities hold that we should disprove

the null hypothesis that “everything is fine

in STEM” before considering action. When

anecdotes are not considered evidence, the lack

PSB 64 (1) 2018

21

of quantitative data itself can become a barrier

to discussions about underrepresentation

(Patridge et al., 2014).

The NSF’s reporting on the interactive

effects of gender and race in its most recent

reports are illustrative of an additional need

to consider intersectionality (i.e., the effects

of multiple aspects of identity on a person’s

life experiences). The results demonstrate

that men of color have had lower rates of

science and engineering degree completion

than women of color for nearly 20 years,

while the opposite is true of white men and

women (National Science Foundation, 2017).

If we look only at gender in the same report,

we see approximate parity in the biological

sciences. If we look at race, we see that African

Americans complete biology degrees at lower

rates than their presence in the American

population would lead us to expect (National

Science Foundation, 2017). These two graphs

would not be enough to prompt many white

scientists to think about addressing the

unique needs of African-American men or

the pressures these students often face outside

the classroom. Only the intersectional graphs

prompt a reader to consider these features.

In this way, intersectional data can help de-

homogenize our thinking about students

from a wide variety of backgrounds.

A well-designed quantitative study can identify

underlying patterns specific to intersectional

identities (Guy, 2013; Clancy et al., 2017).

Nevertheless, quantitative methods will break

down for populations, such as transgender

and gender-nonconforming individuals like

myself, that are not represented widely in

the general population, let alone within the

scientific community (Patridge et al., 2014;

Pryor, 2015). Another population to which

I belong, that of individuals experiencing

disability, is so heterogeneous that the practical

applicability of quantitatively driven solutions

is subject to question. Quantitative surveys

require that researchers generate ideas a

priori that respondents can numerically rank.

Researchers’ beliefs may constrain or bias

which ideas are considered relevant and the

types of solutions proposed. Finally, statistical

analysis emphasizes the most common

patterns within a group, excluding outliers

at quality control steps. Thus, quantitative

methods can erase at least some experiences

of underrepresented individuals.

Let us return to the normative expectation

of scientific epistemology, that the null

hypothesis (“everything is fine in STEM”)

must be disproven before taking action. This

can place a particular burden of disproof

on scientists with stigmatized experiences.

We who experience stigma have both deep

awareness of how far from reality this

hypothesis may be and the greatest incentives

to avoid disclosure. For example, LGBTQA

respondents who were open to few or none

of their colleagues or students also reported

a higher perception of their workplaces as

unsafe, hostile, and lacking in support for

LGBTQA employees (Yoder and Mattheis,

2016). More broadly, anecdotes have long

suggested that sexual harassment and assault

are endemic in science, but a research study

was necessary to highlight their seriousness as

systemic issues in field research (Clancy et al.,

2014). Pressure to avoid disclosure for the sake

of job security can seriously affect a scientist’s

quality of life. Furthermore, non-disclosure

means that colleagues are far less likely to have

information dissuading them from the null

hypothesis, allowing assumptions about both

work climate and stigmatized experiences to

go unchallenged.

Instances like these are where the leaky

pipeline metaphor misdirects us: researchers

PSB 64 (1) 2018

22

can study those at risk of leaking without

fully recognizing the way our own ideas have

been shaped by the pipeline. Individuals and

institutions are reduced to data, as opposed to

humans experiencing subjectively mediated

breakdowns in relationships, responsibilities,

and ethics. Placing empiricism first can

send the implicit message that science is

more important than our colleagues’ well-

being, particularly when outlier feedback is

interpreted as a personality difference rather

than observation from a different social

location. We who face oppression within

broader society and are minoritized in science

often cannot wait for research to demonstrate

to other scientists what we already know.

While empiricism catches up, supporting us

in practice requires personal conversations

about the locations of career pitfalls that are,

to some extent, inherently subjective.

TO SUPPORT DIVERSITY,

BE MORE HUMAN...

OR PERHAPS A FISH

Attempts to fix pipeline leaks solely through

reliance on natural science can cause us to

miss epistemological gaps that our methods

do not address (Roth, 2001). In particular,

applying the scientific lens too broadly or

without sufficient awareness of social factors

may lead us to discard the human part of

science, to base our efforts on statistically

“validated” stereotypes, or to erase certain

forms of experience. While we can begin to

address inclusivity and diversity using natural

science methods, we must remain open to the

possibility that some best practices to support

diversity and inclusion may not be scientific. I

suggest we can further improve our efforts by

(1) improving our knowledge of the dynamics

of social privilege, (2) collaborating with

social scientists trained in qualitative research

methods, and (3) telling our own stories of

navigating career challenges in science.

Social privilege makes daily life easier in ways

that are often invisible to one who holds it.

Graduate mentoring is an illustrative example

of how this manifests in scientific training.

Students of color report a preference for a

mentor of their own race significantly more

often than white students (Blake-Beard et

al., 2011). While racial matching for all

students appears to be correlated with higher

student rankings of mentor support, the rate

at which such matching actually occurs for

students of color is about half that for white

students (Blake-Beard et al., 2011). As a white

graduate student, I was privileged in two

senses: first, it did not occur to me to consider

whether I wanted a white mentor. Second, it

would not have required much effort to make

such a match had I wanted it. Learning that

many students prefer and perceive benefits

from racial matching encourages me to

ask undergraduates of color about their

preferences when discussing future plans.

We who belong to groups underrepresented

in STEM must often navigate cultural and

structural barriers in institutional and social

systems. This results in greater cognitive

loads relative to the privileged minority by

and for whom higher education was initially

constructed. For instance, Indigenous

students must reconcile cultural and

Western understandings of science, typically

within a Western pedagogical framework

(Abrams et al., 2013; Wall Kimmerer, 2015).

African-American graduate students report

questioning their reasons for pursuing STEM

degrees after lethal police actions (Patton,

2014), and completing a graduate degree does

PSB 64 (1) 2018

23

not end experiences of racial discrimination

(Andrist, 2013). Most transgender individuals

have experienced at least one instance

of life-disrupting discrimination such as

severe bullying, assault, job loss, or denial

of accommodations; nearly one in four have

experienced at least three of these (Grant et

al., 2011). Individuals with disabilities may

face pedagogical and physical barriers to

equitable access, even when taught by faculty

supportive of universal design (Lombardi

et al., 2011; Vreeburg Izzo, 2013; Shanahan,

2016). People with invisible, intermittent,

or chronic conditions may have gaps in their

employment records or face difficult trade-offs

between disclosure and stigma from advisors

and employers (e.g., Jones and Brown, 2013).

Given this social context, many of us who fall

into underrepresented groups in STEM are

also in the minority among our demographic

peers because we have had access to scientific

training. Neil deGrasse Tyson has provided

an exemplary discussion of perceived

conflicts between interest in science and

responsibilities to the African-American

community (interviewed in Andrist, 2013).

Scientists who fall into multiple

underrepresented categories must navigate the

challenges of multiple social forces. Each may

compete for time we would rather be spending

on our work; in combination, they may have

greater-than-additive impacts (Armstrong and

Jovanovic, 2015). Interventions that focus on

homogenized populations may compel those

of us with intersectional identities to choose

one specific facet to receive institutional

support. However, our multiple, linked

cognitive loads often cannot be reduced in

such a way, and we can take less for granted in

our daily lives because of the ways these facets

intersect. If faced with sufficient challenges,

we may not be able to fully capitalize on

opportunities that our colleagues and the

scientific community bring to us, even when

we are well-prepared and deeply interested.

Learning about these structural factors and

demonstrating curiosity about individuals’

challenges both creates useful support on a

human level and makes us better colleagues

and advisors (Killpack and Melón, 2016).

Because quantitative methods can exclude

diverse experiences, additional methods

are needed to comprehensively identify and

address issues related to diversity and inclusion

in science. Most natural scientists lack training

in qualitative methods, so collaboration with

social scientists who do is critical in advancing

understanding. Qualitative research also

allows study designs that humanize and

create partnerships with underrepresented

individuals, rather than viewing us as

abstracted research samples or as scientists

getting “distracted” from lab or field studies.

For example, discussions among a highly

heterogeneous cohort of underrepresented

scientists and trainees at the 2014 Northeast

Scientific Training Programs Retreat have

provided valuable, wide-ranging insights on

supporting diversity and inclusion in science

(Campbell et al., 2014). A prominent theme

was a need for greater interdisciplinarity—

defined in this case as using social justice,

communications, and the arts to guide and

disseminate scientific research.

This study raises the possibility of linking

science and the humanities in service to

diversity and inclusion. The scientific mindset

encourages us to look to the data to discover

the most likely path to a graduate degree or

a tenured position in biology, and the most

likely way that certain individuals may leave

that path. A humanistic mindset looks to

individualized experiences to discover all

PSB 64 (1) 2018

24

possible paths to success, providing a map of

roads less traveled. Where the scientifically

rational “likelihood perspective” could risk

activating stereotype threat, a humanistic

“possibility perspective” may be a useful

counter (Schinske et al., 2016). Storytelling

can therefore balance science’s homogenizing

and depersonalizing tendencies. A natural

science perspective does not address practical

questions, such as what a graduate student

with intersectional identities should do if

they experience a specific instance of bias

or harm (e.g., racial harassment) from a

colleague within an institution they perceive

as biased in other ways (e.g., sexist or ableist).

Here, reading narratives from or having

conversations with scientists who have had

similar experiences can make the difference

between choosing to leave academia and using

ingenuity to find or advocate for a healthier

work environment. Stories provide alternative

means of understanding possible options,

help build trust and deepen relationships, and

become tools for healing and sense-making

(Gold, 2008; Harter and Bochner, 2009).

Even brief reading/writing assignments in

introductory biology classrooms highlighting

the diversity of scientists’ identities and

practices can shift students’ perceptions about

scientists in ways that are linked to higher

performance and interest in science (Schinske

et al., 2016). Those of us who are in a position

to do so should consider sharing our stories of

navigating major career challenges, formally

or informally.

Natural scientists spend our educations

learning to identify where things like

pipelines break down, while our counterparts

in the humanities often spend their training

considering where metaphors do so. A critical

place where the leaky pipeline metaphor

breaks down with reference to diversity and

inclusion lies in what that pipeline carries.

Human diversity is defined by its discrete and

overlapping heterogeneity, while water flows,

mixes, and homogenizes. The overuse of

scientific thinking in this context risks treating

students, postdocs, adjuncts, and those on

the tenure track—our (previous) selves—as

interchangeable droplets following universal

rules, subject to an engineered solution

requiring little conversation. Interrogating

this metaphor is not merely intellectual

play: I have highlighted how quantitative

research can homogenize scientist identities,

narrow the range of perceived need, and miss

possible solutions. Although those working

in the humanities do not hypothesize the

way that biologists do, their ways of knowing

can generate insights on where science may

unintentionally become part of the challenges

we try to address. I leave it as an exercise

to the reader to consider how our questions

about the leaky pipeline might change if we

thought of students and academic scientists

as “fish” rather than “water.” To practice my

own recommendation, I will write a follow-up

essay sharing some of my own experiences as

a fish who has navigated between pipeline and

outside “stream” multiple times to highlight

the most important lessons I have learned.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Dr. Kaitlyn Stack Whitney

(UW-Madison), Dr. Alejandra Estrin Dashe

(Metropolitan State University), and four

anonymous reviewers for their helpful

feedback on this essay.

PSB 64 (1) 2018

25

LITERATURE CITED

Abrams, E., P.C. Taylor, and C.-J. Guo. 2013. Contex-

tualizing culturally relevant science and mathematics

for indigenous learning. International Journal of Sci-

ence and Mathematics Education 11: 1–21.

Andrist, L. 2013. Neil deGrasse Tyson and the politics

of representation. V. Chepp, D. Dean, and L. Andrist

[eds.],. The Sociological Cinema: Teaching & Learn-

ing Sociology Through Video. Available at: http://www.

thesociologicalcinema.com/videos/neil-degrasse-ty-

son-and-the-politics-of-representation.

Armstrong, M.A., and J. Jovanovic. 2015. Starting at

the crossroads: Intersectional approaches to institu-

tionally supporting underrepresented minority women

STEM faculty. Journal of Women and Minorities in

Science and Engineering 21: 141–157.

Barr, D.A., M.E. Gonzalez, and S.F. Wanat. 2008. The

leaky pipeline: Factors associated with early decline in

interest in premedical studies among underrepresented

minority undergraduate students. Academic Medicine

83: 503-511.

Blake-Beard, S., M.L. Bayne, F.J. Crosby, and C.B.

Muller. 2011. Matching by race and gender in mentor-

ing relationships: Keeping our eyes on the prize. Jour-

nal of Social Issues 67: 622–653.

Buzzanell, P.M., Z. Long, L.B. Anderson, K. Kokini,

and J.C. Batra. 2015. Mentoring in academe: A femi-

nist poststructural lens on stories of women engineer-

ing faculty of color. Management Communication

Quarterly 29: 440–457.

Campbell, A.G., R. Skvirsky, H. Wortis, S. Thomas, I.

Kawachi, and C. Hohmann. 2014. NEST 2014: Views

from the trainees -- Talking about what matters in ef-

forts to diversify the STEM workforce. CBE - Life Sci-

ences Education 13: 587–592.

Chesler, N.C., G. Barabino, S.N. Bhatia, and R. Rich-

ards-Kortum. 2010. The pipeline still leaks and more

than you think: A status report on gender diversity in

biomedical engineering. Annals of Biomedical Engi-

neering 38: 1928–1935.

Clancy, K.B.H., K.M.N. Lee, E.M. Rodgers, and C.

Richey. 2017. Double jeopardy in astronomy and plan-

etary science: Women of color face greater risks of

gendered and racial harassment. Journal of Geophys-

ical Research: Planets 122: 1610–1623.

Clancy, K.B.H., R.G. Nelson, J.N. Rutherford, and K.

Hinde. 2014. Survey of Academic Field Experiences

(SAFE): Trainees report harassment and assault. PLoS

ONE 97: e102172.

Clark, J., D. Dodd, and R.K. Coll. 2008. Border cross-

ing and enculturation into higher education science

and engineering learning communities. Research in

Science & Technological Education 26: 323–334.

Cohen, L., J. Duberley, and M. Mallon. 2004. Social

constructionism in the study of career: Accessing the

parts that other approaches cannot reach. Journal of

Vocational Behavior 64: 407–422.

Dennehy, T.C., and N. Dasgupta. 2017. Female peer

mentors early in college increase women’s positive ac-

ademic experiences and retention in engineering. Proc

Nat Acad Sci USA 114: 5964–5969.

Dweck, C.S. 2000. Self-theories: Their Role in Motiva-

tion, Personality, and Development (Essays in Social

Psychology). 1st ed. Taylor & Francis Group, LLC,

New York, NY.

Eames, C., and B. Bell. 2005. Using sociocultural

views of learning to investigate the enculturation of

students into the scientific community through work

placements. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathemat-

ics, and Technology Education 5: 153–169.