IN THIS ISSUE...

FALL 2021 VOLUME 67 NUMBER 3

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

A PUBLICATION OF THE BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA

Lee Kass: Eliminate standardized tests

for grad school...... p. 181

Welcome to new BSA employees Tricia Jackson

& Jennifer Hartley.... pp. 167/185

Virtual Congressional Days Visit report from

Taylor AuBuchon-Elder & Mary Sagatelova.... p. 160

The Little Red Hen

&

Culture Change

by David Asai

Botany 2021 Speaker

Fall 2021 Volume 67 Number 3

PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN

Editorial Committee

Volume 67

FROM THE EDITOR

David Tank

(2021)

Department of Biological Sci-

ences

University of Idaho

Moscow, ID 83844

dtank@uidaho.edu

James McDaniel

(2022)

Botany Department

University of Wisconsin

Madison

Madison, WI 53706

jlmcdaniel@wisc.edu

Seana K. Walsh

(2023)

National Tropical Botanical

Garden

Kalāheo, HI 96741

swalsh@ntbg.org

Greetings,

In this issue of PSB, we present the BSA’s

new strategic plan and, as always, highlight

many society efforts that fall into each of

the four strategic priorities.

These topics are echoed in the report from

the International Affairs Committee, an

opinion piece on standardized admission

exams, and in our feature article by David

Asai, which I am particularly excited to

share.

We celebrate the research and scholarly

excellence of our Botany 2021 award

winners, as well as the ongoing success of the

BSA’s science education programs. We are

also delighted to feature many of our science

communicators who enthusiastically

educate the public about plants and plant

science and present the reports from our

Public Policy Award winners who attended

this year’s congressional visit day.

One of the highlights of being PSB editor

is hearing from BSA members about their

endeavors to promote and support botany

and botanists. Stay tuned to the PSB for

more in 2022!

Sincerely,

151

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SOCIETY NEWS

BSA Announces New Strategic Plan..............................................................................................................152

Report from the BSA’s International Affairs Committee......................................................................157

National Botanical and Natural History Societies and Organizations............................................158

Report from Virtual Congressional Visits Day.............................................................................................160

A SciComm Celebration.........................................................................................................................................164

BSA Welcomes New Accounting Manager, Tricia Jackson..............................................................167

Botanical Society of America’s Award Winners (Part 2) ......................................................................168

SPECIAL FEATURES

The Little Red Hen and Culture Change.......................................................................................................174

Opinion: It’s Time to Eliminate Standardized Tests for Graduate School Admissions ......181

SCIENCE EDUCATION

Welcome to Jennifer A. B. Hartley! BSA’s New Education Programs Supervisor.................185

Farewell to Jodi Creasap Gee.............................................................................................................................186

Update on PlantingScience and Master Plant Science Team...........................................................187

PlantingScience Mentors still needed for Fall 2021 Teams...............................................................188

PlantingScience incorporated in Science Outreach Course at Syracuse University ...........188

STUDENT SECTION

Advice from the Careers in Botany Luncheon ..........................................................................................192

Papers to Read for Future Leaders ..................................................................................................................194

MEMBERSHIP NEWS

Renewal Season Has Started! .............................................................................................................................195

Introducing the 2021-2022 BSA Student Social Media Liaison Teressa Alexander...........196

Thank you Sonal!.........................................................................................................................................................196

BOOK REVIEWS

............................................................................................................................................................197

152

SOCIETY NEWS

STRATEGIC PRIORITIES

To ensure that we set forth a path that will

build a stronger botanical community and

serve our mission, the Botanical Society of

America embarked on the process of creating

a new 5-year strategic plan in 2020. BSA

membership was surveyed and a diverse

and broad coalition of members debated

and discussed current and future needs.

The resulting priorities, goals, and strategies

were finalized and approved at the 2021 BSA

Members’ Business Meeting on July 22, 2021.

The strategic plan is a culmination of a very

intentional multi-step process in which we

prioritized inclusion, transparency, and BSA

community involvement. The BSA officers,

committees, and staff will take the plan,

outlined below, and move forward in the

BSA Announces New Strategic Plan

As most of you know, the Society spent much of the last year developing a new Strategic Plan. The

strategic plan is a culmination of a very intentional multi-step process in which we prioritized

inclusion, transparency, and BSA community involvement.

We are proud to present the revised BSA Mission statement and Strategic Plan to you (available

at https://botany.org/file.php?file=SiteAssets/home/BSA_Strategic_Plan_2021.pdf), as it was

approved by the BSA Council and at the All Members Business meeting in July 2021. Our staff

and leadership will be working on the implementation of several of these goals and strategies in the

coming year.

I want to thank our past President, Cindi Jones, for her leadership in this area as well as the 30

members of our Strategic Planning Committee and all our Section and Committee Chairs who

provided feedback over this last year.

-Michael Donoghue, BSA President

OUR MISSION:

To inspire and promote an inclu-

sive global community committed to

advancing fundamental knowledge

and innovation in the botanical

sciences for the benefit of people and

the environment.

next five years to implement changes that will

make the BSA community stronger, more

connected, and ready for global changes and

the future of plant science.

PSB 67(3) 2021

153

HUMAN DIVERSITY, EQUITY

AND INCLUSION (DEI)

Goal 1: The BSA will be an antiracist and

anti-discriminatory society.

Strategies

1.1 Offer DEI leadership training opportunities

to members, including students, that encourage

and foster development as inclusive leaders and

innovative educators.

1.2 Analyze all policies, practices, and expenditures

of the society to determine if and how they may be

leading to DEI disparities, and then eliminate or

revise policies and cease practices and activities

that do not support DEI goals.

1.3 Foreground considerations of diversity, equity

and inclusion in all society policies and practices.

1.4 Develop activities and opportunities that

extend beyond the BOTANY conference and

that do not present financial barriers for member

participation.

Goal 2: The BSA will be a scientific society

whose membership reflects the diversity of

society as a whole.

Strategies

2.1 Increase visibility of who is a botanist,

showcasing the diversity of the profession and the

scientists themselves.

2.2 Prioritize collaborations with HSIs/HBCUs/

MSIs/Tribal and Community colleges and with

other professional societies and organizations to

expand access to and inclusion of their students in

botanical career pathways.

2.3 Increase recruitment and retention of BIPOC

members.

2.4 Increase the diversity of leadership on the

Board and all BSA committees.

Goal 3: The BSA will be a leader in

developing initiatives to recruit and support

diversity and in advocating for institutions

(academic, government, etc.) to recognize

and reward the diversity enhancing activities

of their members.

Strategies

3.1 Support and facilitate increased exposure to

the botanical sciences in institutions that serve

underrepresented groups.

3.2 Develop support documentation that will help

encourage members to advocate for promotion

and tenure metrics that reward contributions to

DEI at their institutions.

3.3. Advocate for the importance of diverse

perspectives and inclusive excellence in all aspects

of science and science education.

Goal 4: The BSA will actively evaluate

its progress in recruiting and retaining

members from underrepresented groups,

and in understanding inequities in access

and opportunity among its members.

Strategies

4 .1 Collect and make available demographic data

to be used in assessment and planning following

IRB protocols to ensure privacy.

4.2 Develop and deploy tools for assessing the

differential impact of access to existing and future

opportunities (e.g., PLANTS), awards, grants, etc.

4.3 Collect data to understand why individuals

join and leave the Society.

4.4 Share data and assessment with the

membership on an annual basis to regularly revise

policies and practices that improve support for

diversity, equity, and inclusion.

PSB 67(3) 2021

154

RESEARCH AND SCHOLARLY

EXCELLENCE

Goal 5: The impacts of BSA publications

(American Journal of Botany, Applications

in Plant Sciences, Plant Science Bulletin) will

increase, as evidenced by various metrics.

Strategies

5

.1 Broaden the scope of research represented in

BSA journals and at conferences while supporting

the current core of the society in organismal,

structural, developmental, and evolutionary

biology.

5.2 Attract more researchers from a wide range

of plant-related areas (e.g., conservation, forestry,

horticulture, plant-microbe interactions) to our

publications and conferences.

5.3 Create and promote greater international,

cross- and interdisciplinary opportunities for

collaboration within BSA journals.

5.4 Move toward an entirely open access publication

model while maintaining low publication fees for

members.

Goal 6: The recognition of botany as an

essential biological and environmental

discipline will increase within the scientific

community.

Strategies

6.1 Promote the science of botany as foundational

to global restoration and actively promote

interdisciplinary efforts related to repair earth

systems.

6.2. Increase the promotion of botany and its

importance as a professional scientific discipline to

confront public and professional misperceptions.

6.3 Provide expertise to funding agencies on

current/future issues related to botany.

6.4. Promote inclusive ‘plant-person’ identities

to address negative associations with botanical

sciences and science in general (elite, exclusive, etc.)

6.5 Increase recognition of the value of indigenous

botanical knowledge

Goal 7: The increased prominence of the

BSA as a global leader in research, teaching,

and advocacy related to the botanical

sciences will be reflected in at least a 5%

membership increase over three years.

Strategies

7.1 Establish the BSA as a prominent leader on

current issues related to our field and the mission

of the society.

7.2 Recruit and retain more professionals at all

career stages who study, teach and/or promote

botanical sciences to BSA from all forms of

academic and non-academic institutions.

7.3 Recruit/retain/support members from outside

of the society, or who have been affiliated in the

past, through presentation, service, or publication

opportunities

7.4 Increase international participation in society

activities and governance.

7.5 Evaluate the possibility of revising membership

fees to include additional categories/price points

to better accommodate international members.

Goal 8: The BSA will provide its members

with increased support for scholarly

excellence and research.

Strategies

8.1 Increase the number of research awards and

strategically increase or revise honors and awards

to reflect BSA core values.

8.2 Promote discussions with decision-makers

in funding agencies (e.g., The National Science

Foundation) with the aim of increasing

PSB 67(3) 2021

155

understanding of the importance of botany and

providing additional funding opportunities.

8.3 Create new mechanisms for the recognition of

scholarly excellence that promote our members

beyond the society.

Goal 9: The annual BOTANY conference

will be the premier venue to showcase and

disseminate the latest research in botany.

Strategies

9.1 Increase access to the conference, especially

for members of underrepresented groups.

9.2 Increase promotion of and access to special

lectures/symposia beyond the conference.

9.3 Incorporate a virtual component in all future

conferences.

ORGANIZATIONAL

IMPACT AND VISIBILITY

Goal 10: The appreciation of plants and the

field of botany will increase in society.

Strategies

1

0.1 Connect BSA resources with non-BSA

audiences through stronger collaboration with

other regional, national and international plant

societies.

10.2 Increase emphasis on science communication

and the development of science communication

skills.

10.3 Highlight BSA members’ expertise and

the centrality of plants in solving pressing

environmental and societal problems (climate

change, biodiversity loss, benefits of nature to

mental and physical health, etc.)

10.4 Engage with the public to promote curiosity

and appreciation for plants, nature, and science.

Goal 11: The BSA will be a major contributor

in efforts to educate the public about

science and to shape regional, national

and international policy regarding science

and conservation; the BSA will be seen as

a premier source of unbiased botanical

information.

Strategies

11.1 Reward BSA members for leadership efforts

beyond the BSA in areas such as innovation,

strategic communication, etc.

11.2 Initiate or collaborate on public policy

efforts broadly focused on science, botany, and

pressing environmental stresses (climate change,

biodiversity loss, etc.).

11.3 Amplify the visibility of BSA members

participating in regional, national and

international efforts that promote the role of

science in society, influence public policy, shape

educational initiatives, etc.

11.4 Lead/participate in cross-society data

collection efforts to better understand

opportunities and challenges, and work toward

common goals focused on human diversity and

scientific advancement.

Goal 12: The BSA will be recognized as

the leader in education for the botanical

sciences.

Strategies

12.1 Encourage, assist, and advocate for life science

educators at all levels to include botanical science

in their curricula, standards, and lesson plans.

12.2 Ensure that education and outreach programs

are grounded in evidence-based best practices of

botanical science education and contribute to our

goals in broadening participation.

12.3 Lead workshops throughout the year targeted

toward students and early career academics

and naturalists to foster future generations of

exceptional educators in botanical science.

PSB 67(3) 2021

156

PROFESSIONAL

DEVELOPMENT

Goal 13: All members of the BSA will share

a strong sense of belonging to the society.

Strategies

13.1 Establish and support networks of affinity

groups that enhance career development by

providing accessible channels of communication

among diverse members.

13.2 Develop and maintain strong frameworks that

span career stages and peer mentoring focused on

professional development.

13.3 Collect data to better understand what the

BSA can do to support student members as they

transition to professional positions, thus reducing

attrition from botanical careers at these junctures.

13.4 Continue to increase the number and size

of awards for graduate students/postdocs in

outreach.

Goal 14: Membership in the BSA by people

outside of academia will increase by at least

10% over five years.

Strategies

14.1 Highlight the many diverse and cross-

disciplinary pathways to successful careers in the

botanical sciences outside of academia through

publications, conferences and activities, and

develop initiatives to support and retain BSA

student members to transition to non-academic

professional careers.

14.2 Review and revise our governance structure

to generate benefits for non-academic career

members, accounting for career path and career

stage as two important axes of diversity.

14.3 Review the use of a Careers job board on our

website and consider ways to better disseminate

and heighten awareness of non-academic careers.

14.4 Create tools for career exploration, mentoring,

and building connections across interdisciplinary

boundaries.

Goal 15: The Board, committee chairs,

and staff will be well prepared to lead the

organization with foresight and fiduciary

responsibility.

Strategies

15.1 Provide leadership training opportunities

for all Board members, Committee Chairs, and

Section Chairs.

15.2 Create a professional development plan for

all staff to ensure continued professional growth

and incorporate best practices in all aspects of

management.

15.3 Build institutional knowledge and facilitate

the smooth transfer of operations and relevant

resources to future society leadership.

PSB 67(3) 2021

157

BSA’s International Affairs Committee met

this summer prior to Botany 2021. We are

happy to share with you some details about

the committee and what issues we have been

discussing recently. Members of the committee

include Hugo Cota-Sanchez (Chair); Cecilia

Zumajo (Student Representative); Johanne

Brunet; Suman Neupane; Shengchen Shan;

Heather Cacanindin, Executive Director,

ex officio; Melanie Link-Perez, Program

Director, ex officio; and Michael Donoghue,

President, ex officio.

The International Affairs Committee aims

to link BSA with other national botanical

societies outside the United States and to

connect BSA members to international

botanical events, including the International

Botanical Congress (IBC), which is held every

six years. The committee seeks to support

young botanists attending the IBC, as well

as other important international meetings.

The committee informs the Society regarding

international activities impacting the study of

plants through articles in the Plant Science

Bulletin, symposiums and colloquium at the

annual Botany meetings, and other activities.

Each year, new members join the committee

as the same number of members rotates

off. This committee is chaired by a member

serving their third year on the committee.

At our recent meeting, we spent a good deal

of time discussing international botanical

meetings that are in the works. We would

like to make our membership aware of the

following:

• Latin American Botanical Congress –

Cuba (month TBD) 2022

• Mexican Botanical Congress – October

2022

• Annual Meeting of the Canadian

Botanical Association – Canada (month

TBD) 2022

• National Botanical Congress – Brazil

(month TBD) 2022

• International Congress of Sexual Plant

Reproduction - Prague, Czech Republic,

June 2022 (https://www.iasprr.org/index.

php?browse=news&nid=52)

• International Conference on Botany

and Plant Science – Helsinki, Finland,

July 2022 (https://waset.org/botany-

and-plant-science-conference-in-july-

2022-in-helsinki)

• Association of Tropical Biology and

Conservation – Cartagena, Colombia,

July 2022

• International Botanical Congress

Madrid, Spain, July 2024

If you know of any upcoming international

activity or events that should be shared with

our BSA community, please email those

to bsa-manager@botany.org so we can add

them to our list and assist in their promotion.

In December 2021, BSA will send out a call

for committee service applications. We will be

seeking two new members for the International

Affairs Committee and one student

representative as well. Please consider applying

for committee service and joining in 2022!

REPORT FROM THE BSA’S INTERNATIONAL

AFFAIRS COMMITTEE

PSB 67(3) 2021

158

NATIONAL BOTANICAL AND NATURAL HISTORY

SOCIETIES AND ORGANIZATIONS

For more information about the committee, see https://cms.botany.org/home/governance/

international-affairs-committee.html.

(Compiled by IAC, July 2021)

China

• Botanical Society of China: http://

www.botany.org.cn/English/content.

aspx?PartNodeId=109

• China Wild Plant Conservation Association

(CWPCA): https://www.wpca.org.cn/

Colombia

• Asociación Colombiana de Botánica: https://

www.biciq.com/events/asociacion-colombi-

ana-de-botanica-afiliacion/

• FaceBook: https://www.facebook.com/Aso-

ColBotanica/

Cuba

• Sociedad Cubana de Botánica: http://www.

socubot.cu

Czechia

• Czech Botanical Society: https://botanospol.

cz/en/node/42

Denmark

• Botanical Society of Denmark: https://bota-

niskforening.dk

Europe

• Federation of European Societies of Plant

Biology: https://fespb.org

France

• Societé Botanique de France: https://societe-

botaniquedefrance.fr

Germany

• German Society for Plant Sciences: https://

www.deutsche-botanische-gesellschaft.de/en/

home

Argentina

• Sociedad Argentina de Botánica: https://bo-

tanicaargentina.org.ar

Australia

• Australian Native Plant Society: http://anpsa.

org.au

Australasia

• Australasian Systematic Botany Society Inc.:

http://www.asbs.org.au

Belgium

• The Royal Botanical Society of Belgium

http://www.botany.be/en/node/1

Brazil

• Sociedade Botánica de São Paulo: https://bo-

tanicasp.org/en

• Sociedade Botánica do Brasil: https://www.

botanica.org.br

Canada

• Canadian Botanical Association /

L’Association Botanique du Canada: https://

www.cba-abc.ca

• Canadian Wildlife Federation: https://cwf-fcf.

org/en/explore/gardening-for-wildlife/plants/

buy/native-plant-suppliers/native-plant-sup-

pliers/on/204.html

• Nature Conservancy of Canada: https://www.

natureconservancy.ca/en/

Chile

• Sociedad Botáncia de Chile: http://socbo-

tanica.cl

PSB 67(3) 2021

159

NATIONAL BOTANICAL AND NATURAL HISTORY

SOCIETIES AND ORGANIZATIONS (cont'd.)

Great Britain and Ireland

• Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland:

http://www.asbs.org.au

Internet Directory for Botany

• Botanical societies, international botanical

organizations: https://www.bgbm.org/IDB/

botsoc.html

India

• Indian Botanical Society: https://indianbot-

soc.org/index.php

Israel

• The Israeli Society of Plant Sciences: https://

www.israelplant.org.il/en

Italy

• Società Botanica Italiana: https://www.soci-

etabotanicaitaliana.it

• International Union for the Conservation of

Nature

International Union for the Conservation of Nature

• https://www.iucn.org

Japan

• Botanical Society of Japan (BSJ): https://bsj.

or.jp/index-e.php

Mexico

• Asociación Mexicana de Orquideología,

A.C.: http://amo.com.mx/indexesp.html

• Sociedad Botánica de México: https://www.

socbot.mx

• Sociedad Mexicana de Cactología, A.C.:

http://www.mexican.cactus-society.org/eng-

lish.html

Philippines

• Association of Systematic Biologists of the

Philippines: http://asbp.org.ph

Poland

• Polish Botanical Society: https://pbsociety.

org.pl/default/en/

Spain

• Sociedad Botánica Española: http://www.rjb.

csic.es/jardinbotanico/jardin/contenido.php?

Pag=293&tipo=noticia&cod=7219

Switzerland

• Swiss Botanical Society: https://botanica-

helvetica.ch/en

United Stares of America

• American Society of Plant Taxonomists:

https://www.aspt.net

• Botanical Society of America: https://botany.org

• California Native Plant Society: https://www.

cnps.org

• The Nature Conservancy: https://www.na-

ture.org/en-us/

• Torrey Botanical Society: http://www.torrey-

botanical.org

• Southern Appalachian Botanical Society:

https://sabs.us

Other International Societies

• International Association for Plant Taxono-

my: https://www.iaptglobal.org

• The International Compositae Alliance:

https://www.compositae.org

AASP – The Palynological Society: https://

palynology.org

• The International Organisation of Palaeo-

botany https://palaeobotany.org

PSB 67(3) 2021

160

A Personal Account by

Mary Sagatelova, MPA

Public affairs—and by extension public

policy—can broadly be defined as purposeful

action taken by the government in order to

address a general issue. Seemingly simple but

fraught with complexity, the field of public

affairs is often overlooked as one of the most

important professional fields in our society.

Every niche within society is affected in

some capacity by government affairs and the

implementation of public policy. Perhaps most

salient is the effect of public policy decisions

on science and scientific research. Policy

decisions have the capability of prioritizing

research areas, blocking or authorizing

projects, and most importantly, funding our

work through federal allocation.

REPORT FROM VIRTUAL

CONGRESSIONAL VISITS DAY

Each year, the BSA Public Policy Committee awards two early-career botanists the opportunity to

attend the American Institute of Biological Sciences’ Congressional visits Day. This event is hosted by

the Biological and Ecological Sciences Coalition, and recipients obtain first-hand experience at the

interface of science and public policy. The first day includes a half-day training session on science

funding and how to effectively communicate with policymakers provided by AIBS. Participants then

meet with their Congressional policymakers, during which they will advocate for federal support of

scientific research. This article details the experiences of this year’s recipients.

As a graduate student studying Evolution,

Ecology, and Organismal Biology, I am

extremely cognizant of the potential policy

implications of scientific research, especially

within botanical research. Seldom do I come

across research that does not reference policy

application in the real world. The more I saw

these policy connections, the more I became

interested in working at this intersection of

science and policy. As such, I felt incredibly

honored by the opportunity to be recognized

by the Botanical Society of America as a Public

Policy Award recipient, and to be afforded

the opportunity to attend the 2021 Virtual

Congressional Visits Day.

The first two days, I participated in a virtual

communications boot camp through the

American Institute of the Biological Sciences

(AIBS). Despite the virtual setting, I was able

to meet and connect with fellow graduate

students, postdocs, professors, and botanical

professionals, all while learning about the

specifics of the policy process. This training

covered a wide range of topics! We were

provided with the tools necessary to craft

exceptional elevator pitches, interact with

the media, and effectively communicate our

message to decision makers. Through a variety

of multimedia resources, practice pitches, and

interviews, the training provided through

AIBS was instrumental in preparing me for

the virtual congressional visits!

PSB 67(3) 2021

161

Working within a regional pairing, I

successfully met with the offices of five different

congressmen across Indiana and Ohio. In these

meetings, we advocated for enhanced funding

for the National Science Foundation (NSF),

specifically encouraging representatives and

senators to approve the proposed $10.2 billion

budget for NSF. Further, we asked for support

for the then-newly introduced Research

Investment to Spark the Economy (RISE) Act.

This act would authorize approximately $25

billion across different federal agencies to be

allocated to independent research institutions,

national laboratories, and universities, with

the specific intent of addressing pandemic

related disruptions to research and learning.

Each of us shared anecdotes of how NSF

funding has been instrumental in our home

states, universities, and labs, elaborating on

how the pandemic has affected our research

and the benefits of increased funding.

Over two days, we met Senator Michael Braun

(R-ID), Representative Trey Hollingsworth

(R-ID), and the offices of Senator Sherrod

Brown (D-OH), Senator Rob Portman (R-

OH), and Senator Todd Young (R-ID).

Each meeting was a unique experience in

which we were able to apply the training we

received just a few days prior and successfully

communicate our messages in advocating for

increased scientific funding. I was particularly

encouraged by the office of Senator Brown,

who intended to introduce policy specifically

targeting systemic issues within STEM.

Specifically, Brown’s office asked about our

experiences in STEM and shared intentions

of increasing funding to remove barriers in

STEM for minority groups, as well as creating

new government jobs for more scientists!

I am incredibly fortunate that I was able

to participate in the AIBS training and the

virtual congressional visits. Public policy often

seems like an impervious and intimidating

field because of the perceived complexity of

politics. However, through this experience, I

was able to build the basic skills and experience

necessary to effectively confer on public policy

and communicate science professionally. I

look forward to building upon these skills and

continued scientific advocacy.

(Mary is from the College of Arts and Sciences

Department of Evolution, Ecology, and

Organismal Biology; The John Glenn College of

Public Affairs Public Policy and Management)

Taylor AuBuchon-Elder’s

Experience

I was fortunate enough to receive BSA’s

Public Policy Award in 2020 just prior

to the beginning of the pandemic in the

United States. My fellow award recipient,

Mary, and I were planning accommodations

and preparing for the whirlwind that is

Congressional Visits Day (CVD) to argue for

NSF funding. Sadly, we never made it there in

person; but I think this year’s virtual format

for both the American Institute of Biological

Sciences (AIBS) Communications Bootcamp

and CVD was an incredible success. I feel

truly grateful that I was able to be a part of it.

PSB 67(3) 2021

162

The AIBS Communications Bootcamp’s

success, I believe, was because of Dr. Jyotsna

Pandey and the supportive and welcoming

attendees. Jyotsna led us through two days of

lectures, group exercises, and career panels—

all of which I found to be enlightening and

challenging. One thing I think scientists can

always improve upon is our communication

of scientific ideas, especially in our areas of

expertise. A group exercise where you have to

describe your work’s purpose in 1 minute will

definitely help get you there!

To prepare for our meetings with

representatives, we reviewed best practices

for talking to policy makers: Why should

they care? What motivates them? Are they

up for re-election? While we went over

communication strategies collectively, our

job as individuals was to read up on our

own representatives—their voting record,

committees on which they serve, political

viewpoints, etc. I live in Missouri so I have

been aware of my representatives’ conservative

voting record when it comes to federal

spending, but I was optimistic we could make

a strong argument for basic research funding

given the last year’s strong reliance on robust

science. I was assigned to Representative Ann

Wagner (R-MO), Senator Roy Blunt (R-MO),

Senator Josh Hawley (R-MO)—along with my

partner, Claire’s, representatives in Tennessee,

Senator Marsha Blackburn (R-TN) and

Senator Bill Hagerty (R-TN). We knew asking

for increased federal funding for the NSF was

going to be a tall order.

Our asks on behalf of the AIBS were $10.2

billion for NSF for FY 2022, President Biden’s

budget request, an increase from FY 2021’s

$8.5 billion, and for our representatives

to support or co-sponsor the Research

Investment to Spark the Economy (RISE)

Act to address pandemic-related disruptions

and closures in basic research funded by the

federal government. I’m not sure if there’s ever

been a more important time to stress the need

for increased investment and engagement in

NSF-funded science. We knew it was pertinent

to tell our stories and bring the message home

that we all benefit from basic research.

The lab I work in operates almost solely under

NSF funding; and we specialize in cereal

crops—more specifically, we study the genetic

diversity of wild grasses and their relatives,

with the end goal that this knowledge will

provide other scientists and crop breeders with

the necessary building blocks for engineering

more efficient crops in harsher climates.

This is relevant research being in Missouri,

considering our annual corn production value

in 2020 was around $2.4 billion. The current

project we’re working on under NSF funding

also directly employs around 30 people at

several research institutions—truly exciting,

multi-faceted, and collaborative work. When

talking with my representatives, I wanted to

highlight that.

One hurdle the project faced early on was

a large cut to its budget—half of it—when

the NSF-PGRP was specifically targeted in

2018. I’m not sure why someone somewhere

decided the Plant Genome Research Program

needed half the money; maybe it was the

idea that there is “too much” basic research

funding out there—something we heard

when talking to a legislative staffer during

CVD. I admittedly was taken aback slightly

by that idea. And while I did not necessarily

have a retort specifically prepared for it, I

was able to draw from my own experience

in budget cuts. Because our project’s budget

was cut so significantly, we actually lost

the translational part of the work—going

from a project focused on basic research for

PSB 67(3) 2021

163

directly applied results in crops, to a project

heavily focused on just the basic stuff. So

while some Congressional offices vote to cut

basic research funding to shift focus to more

applied work; ironically, they inadvertently

disrupt the downstream applications of said

basic research. I highlighted this point during

our meeting with a legislative staffer, and I

hope it resonated.

The rest of our meetings went on without a hitch

and were generally pleasant and productive,

except for one no-show. Virtual meetings

may not be everyone’s favorite, but I think it

was fairly conducive for our purposes, with a

strict start time and limited interruptions, as

I’m sure would not have been the case if we

were running around Capitol Hill! We made

our cases to the staffers, and they talked to us

about where their bosses stood and what their

current priorities were. Just before we began

our meetings, we were made aware of the

Endless Frontier Act, a large sweeping funding

bill that would pump an historical amount of

money into federally funded science, even

creating a new Directorate at the NSF. The bill

was making its rounds around Congress and

it seemed to be taking up a lot of everyone’s

time, so it came up frequently after we made

our case for NSF funding.

I’m sincerely grateful for the opportunity to

have attended CVD on behalf of BSA. It was

an exciting, educational, and tiring few days

training for and meeting with Congressional

staffers. I learned firsthand how initiatives

and situations can change in a minute and

how succinct and effective we have to be at

arguing for basic research funding (and how

important it is to stay involved!).

(Taylor is from the Donald Danforth Plant

Science Center, St. Louis, MO)

Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections

Join our global community dedicated to the preservation, conservation

and management of natural history collections

spnhc.org

SPNHC 2022: hosted by Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh and National Museums Scotland, UK

SPNHC 2023: hosted by California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, USA, May 28-June 2, 2023

“It’s pronounced “SPINACH!”

spnhc

_

@SPNHC

@www.spnhc.org

SPNHC

PSB 67(3) 2021

164

Tell us a little about yourself as a SciCommer.

When did you become active? What

platforms do you use?

Naomi Volain (NV): I’ve always been a

science communicator in some form in

my career—nutrition, medical advertising,

science teaching and education—but it

wasn’t until 2020 that I started creating plant

and science Comic strips. I put them on the

Comics page of my website, Plants Go Global.

Instagram, Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn

are my social platforms.

Giovanna Romero (GR): I started as a

SciCommer a year ago. I use Twitter, Instagram

and Facebook platforms. These platforms are

linked to BIOWEB Ecuador. BIOWEB is a

webpage managed by Catholic University of

Ecuador. I post every Monday morning about

native plants of Ecuador. The goal is that people

get interested in Ecuadorian plant diversity.

Generally, I upload pictures that I take every

time I go to the field in private preserved areas

or National Parks. When I go to the field, to me,

it is challenging because plants in the Tropics

have varying blooming times. I take pictures

of plants that I think would be attractive to

people (based on flower color, flower forms,

sori form, endemism, habit). Then, I identify

and post them. Sometimes, identification

takes time and it can even require a visit to

local herbaria, like QCA.

A SCICOMM CELEBRATION

Teressa Alexander (TA): I love communicating

plant science through intriguing articles I’ve

read about different plants, but I mainly focus

on cacao trees. My topics surround cropping

systems, climate change, social and economic

issues surrounding the cacao crop. I use

Instagram and Twitter (fairly new to Twitter)

to communicate this work.

Jacob Suissa & Ben Goulet-Scott (SG): Let’s

Botanize (@letsbotanize) is an Instagram-

based science communication series using

plant life to teach about ecology, evolution, and

biodiversity through engaging photography

and thoughtfully produced videos. As

gardening and outdoor recreation increase in

popularity, we are creating a digestible entry

point for a broad audience to indulge their

curiosity about plant life and biology more

generally. We started in January 2021 and are

active on Instagram and YouTube.

At Botany 2021, the BSA hosted the second annual SciComm Celebration.

Plant Science Bulletin

is pleased to highlight several of the SciCommers active in the Botanical community. Editor

Mackenzie Taylor reached out this fall to ask about their experiences and advice. Below are

highlights from their responses and information about how to follow them.

PSB 67(3) 2021

165

What are your strategies for being an

effective SciCommer and/or what have you

learned while engaging in SciComm?

NV: I’m really careful to get the science right,

to make sure the art is expressive, and to be

sure that the text teaches and entertains. The

small space limits of a Comic panel force me

to pare down the information into quick bites.

I’m also mindful of the speed people consume

media, so I work to make my art and words a

quick view.

GR: I began with no experience as a

SciCommer. Actually, I did not know

about it until I read in a tweet, posted by

Botanical Society of America, that what I

was doing is called “SciCommer.” It has been

a learning process and it is still. I started

with no strategies, but I have learned a lot.

My strategies now to engage people with

my posts are combining good pictures with

interesting facts about the plant species

being presented.

TA: I use photography and chart designs

to explain information on topics relevant

to cocoa research, plant biomechanics, and

climate change. By sharing, I’ve learned

about other interesting work in these areas

from other plant scientists/enthusiasts.

SG: As we created content for Let’s Botanize,

over time we realized that plant life is a

much more effective substrate for teaching

about ecology and evolution than we

initially appreciated. For example, plants are

plentiful and stationary, meaning it is easy

to closely observe and interact with them in

natural settings. Also, as the foundational

organisms in most ecosystems, they provide

ample opportunity for discussing ecological

processes. Most people are also already

familiar with the incredible variation

expressed in plants (e.g., the diversity found

in an arboretum, a nursery, or on your dinner

plants) that allows one to see how mutations

arise and lead to evolution in real time. In

addition, we are both PhD Candidates at

Harvard University in the department of

Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, with

a focus on plant evolution, so we are able to

leverage our academic expertise.

What is the most difficult thing about

engaging in SciComm?

NV: The nagging feeling to be constantly

present in social media.

GR: Posts must be very precise. So, to make

the story interesting and short is difficult.

TA: I think the most difficult thing about

engaging in SciComm is staying consistent

with content sharing. As a current graduate

student, I think there has to be a structured

plan of action in order to execute content

sharing consistently.

SG: Determining the fine line between too

much and too little detail. We want to keep

our audience engaged and teach them new

things without losing them in technicalities.

PSB 67(3) 2021

166

What do you consider your strongest

measure of success in SciComm (e.g.,

number of followers, personal engagement,

getting paid for your work)?

NV: The strongest measure is the feedback.

Hearing from people personally, beyond the

number of likes or followers deepens the

meaning of what I’m seeking to accomplish,

which is to create Comics that entertain,

educate, and connect people with plants.

Today I heard Olympic gymnast great Simone

Biles say, “I’m more than my medals.” This

resonated for me. But yes, monetary feedback

would surely validate my feeling of success!

GR: I would say, the strongest measure of

success in SciComm is the number of likes

in every post and sometimes when someone

asks a question or comments about the post.

TA: I consider the strongest measure of success

in SciComm to be engagement. When people

are engaging with your call of action, giving

feedback, asking questions, or just sharing

your content, it shows how impactful your

content is. As a result of high engagement,

gradual increases in followers and eventually

getting paid for your work will occur.

SG: Number of followers, and positive

comments/engagement with our work. Also

our connections with larger institutions such

as The Arnold Arboretum, Harvard Museum

of Science and Culture, and LabXchange.

What has changed about being a SciCommer

while you have been active?

NV: The need for truth and communicating

in science is even more critical since the start

of the COVID pandemic. What’s especially

needed now is for the public to learn, to truly

understand how the process of science works

to gain knowledge.

GR: Well, the fact that I was chosen to

participate as a SciCommer in Botany 2021

changed the way I see this activity. To me it was

unthinkable that posting about Ecuadorian

plants could be shown in a Conference. Being

a SciCommer made me understand that it is

possible to communicate through platforms

and reach a wide range of people.

TA: Platforms such as TikTok and new

Instagram features like reels have encouraged

new creative ways for SciCommers to engage

with their audience. The way I communicate

science can be diversified while reaching

broader audiences with increased creativity.

PSB 67(3) 2021

167

SG: We have been active for less than a year,

so not much. We still feel like we are learning

how to improve ourselves each day.

What would you like people to know

about SciComm?

NV: Communicating science brings science,

scientists, and the scientific process to the

world. SciComm is a deliberate, unique

initiative focused on this!

GR: SciComm is a rewarding activity, and it is

a way to engage people to know about plants.

TA: SciComm is a great way to challenge

misinformation and breakdown the

complexities of scientific language making it

useful and accessible to everyone.

SG: It’s fun and rewarding, but doing it well

takes a lot of forethought, planning, and time.

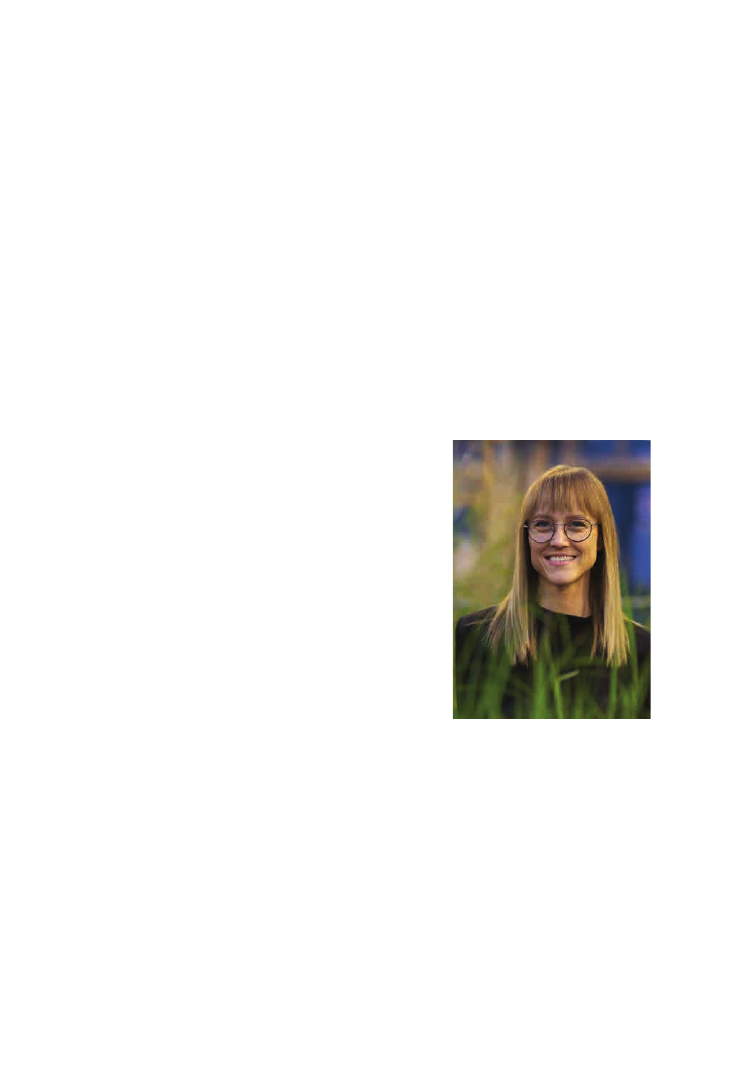

The BSA is pleased to announce the addition

of Tricia Jackson, CPA as the Society’s new

accounting manager. She reports to Executive

Director, Heather Cacaninidin.

Tricia comes to the BSA from public accounting,

where she specialized in audit and assurance

services for non-profit and healthcare clients

in the St. Louis Metropolitan area. She also

has more than 4 years of non-profit experience

working in various accounting roles.

Her other interests include cooking, hiking

through local and state parks, getting lost in

jigsaw puzzles, and hanging out with her two

pet rabbits, Buns and Jolene.

Tricia can be reached at tjackson@botany.org

.

BSA WELCOMES NEW ACCOUNTING MANAGER,

TRICIA JACKSON

PSB 67(3) 2021

168

BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA’S

AWARD WINNERS (PART 2)

CHARLES EDWIN BESSEY TEACHINGAWARD

(BSA in association with the Teaching Section and Education Committee)

Dr. Montgomery is an outstanding scientist

and one of the foremost ambassadors

of Botany today. Not only has she made

significant and lasting contributions to

our understanding of determinants of

cyanobacterial cell shape, signaling, and light

dependent Physiology but she has also burst

onto the scene as a public intellectual and

authority on plant science and mentoring.

With a huge Twitter following, she engages

and challenges us through sharing her science

and research on pedagogy through social

media, podcasts, online seminars, and special

lectures both for her scientific colleagues and

for the general public. Beronda is also one of

the co-founders of #BlackBotanistsWeek.

Her extraordinary and innovative approaches

to mentoring and teaching are documented

in a number of peer-reviewed articles

on pedagogy, mentoring and diversity in

STEM. In her work, she links the domains

of plant science and mentoring while

sharing that mentees, like plants, flourish

or struggle based on their environment—

not as a result of any inherent deficiency.

Dr. Montgomery has been described as a

visionary, an outstanding educator, and an

engaging source of inspiration by colleagues

and students alike. Her transformative

leadership encourages and enables others

to become more deeply engaged in teacher-

scholar outreach and training. As one of her

nominators described, “Prof. Montgomery is

a giant walking among us. Her scholarship

around equity-engaged mentorship has

awakened multiple generations of plant

scientists of a pathway to do better. She has

brought acclaim and welcome attention

to plant science, and has forged a unique

melding of her science, her advocacy and her

teaching…. I can think of no one who better

fits the criteria of the Bessey Award or who is

more deserving of public recognition for her

work on behalf of all of us.”

DR. BERONDA MONTGOMERY

MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY

PSB 67(3) 2021

169

BSA CORRESPONDING MEMBERS AWARD

Corresponding members are distinguished senior scientists who have made outstanding contribu-

tions to plant science and who live and work outside of the United States of America. Corresponding

members are nominated by the Council, which reviews recommendations and credentials submitted

by members, and elected by the membership at the annual BSA business meeting. Corresponding

members have all the privileges of life-time members.

Dr. Peter Linder Prof. Jianquan Liu Dr. Marie-Stéphanie Samain

THE GRADY L. AND BARBARA D. WEBSTER

STRUCTURAL BOTANY PUBLICATION AWARD

This award was established in 2006 by Dr. Barbara D. Webster, Grady’s wife, and Dr. Susan V.

Webster, his daughter, to honor the life and work of Dr. Grady L. Webster. After Barbara’s passing in

2018, the award was renamed to recognize her contributions to this field of study. The American Soci-

ety of Plant Taxonomists and the Botanical Society of America are pleased to join together in honor-

ing both Grady and Barbara Webster. In odd years, the BSA gives out this award and in even years,

the award is provided by the ASPT.

Kamil E. Frankiewicz, Alexei Oskolski, Łukasz Banasiak, Francisco Fernandes, Jean-

Pierre Reduron, Jorge-Alfredo Reyes-Betancort, Liliana Szczeparska, Mohammed

Alsarraf, Jakub Baczyński, Krzysztof Spalik

Parallel evolution of arborescent carrots (Daucus) in Macaronesia American Journal of

Botany 107(3): 394-412 (March 2020)

AWARDS FOR ESTABLISHED SCIENTISTS

GIVEN BY THE SECTIONS

MARGARET MENZEL AWARD

(GENETICS SECTION)

The Margaret Menzel Award is presented by the Genetics Section for the outstanding paper presented

in the contributed papers sessions of the annual meetings

.

Irene Liao, Duke University, For the presentation: Identifying candidate genes contributing to

nectar trait divergence in the selfing syndrome (Co-authors: Gongyuan Cao, Joanna Rifkin, and

Mark Rausher)

Switzerland

China

Mexico

PSB 67(3) 2021

170

EDGAR T. WHERRY AWARD

(PTERIDOLOGICAL SECTION AND THE AMERICAN FERN SOCIETY)

The Edgar T. Wherry Award is given for the best paper presented during the contributed papers session of

the Pteridological Section. This award is in honor of Dr. Wherry’s many contributions to the floristics and

patterns of evolution in ferns.

Ana Gabriela Martinez, National Autonomous University of Mexico, UNAM. Faculty of Higher

Studies Zaragoza, For the Presentation: Disentangling the systematics of the Elaphoglossum

petiolatum complex (Dryopteridaceae) (Co-Author: Alejandra Vasco)

Honorable Mention

Jacob Watts, University of Cambridge, For the Presentation: Microarthropods Increase Sporo-

phyte Formation and Enhance Fitness of Ferns. (Co-Authors: Aidan Harrington, James Watkins)

David Wickell, Cornell University, For the Presentation: Gene fractionation and differential

expression of homoeologues following whole genome duplication in the tree fern, Alsophila

spinulosa. (Co-Authors: Fay-Wei Li, Li-Yaung Kuo, Xiong Huang, and Quanzi Li)

ISABEL COOKSON AWARD

(PALEOBOTANICAL SECTION)

Established in 1976, the Isabel Cookson Award recognizes the best student paper presented in the

Paleobotanical Section.

Michael D’Antonio, Stanford University, For the Presentation: “Sigillaria from the Wuda

Tuff: the implications of new species and internal anatomy for lepidodendrid life history

reconstruction.” (Co-Authors: Kevin C. Boyce, Wei-Ming Zhou, and Jun Wang)

KATHERINE ESAU AWARD

(DEVELOPMENTAL AND STRUCTURAL SECTION)

This award was established in 1985 with a gift from Dr. Esau and is augmented by ongoing

contributions from Section members. It is given to the graduate student who presents the

outstanding paper in developmental and structural botany at the annual meeting.

Molly B. Edwards, Harvard University, For the Presentation: A developmental a transcriptional

framework for pollinator-driven evolutionary transitions in petal spur morphology in Aquilegia

(columbine). (Co-Authors: Evangeline S. Ballerini and Elena M. Kramer)

PSB 67(3) 2021

171

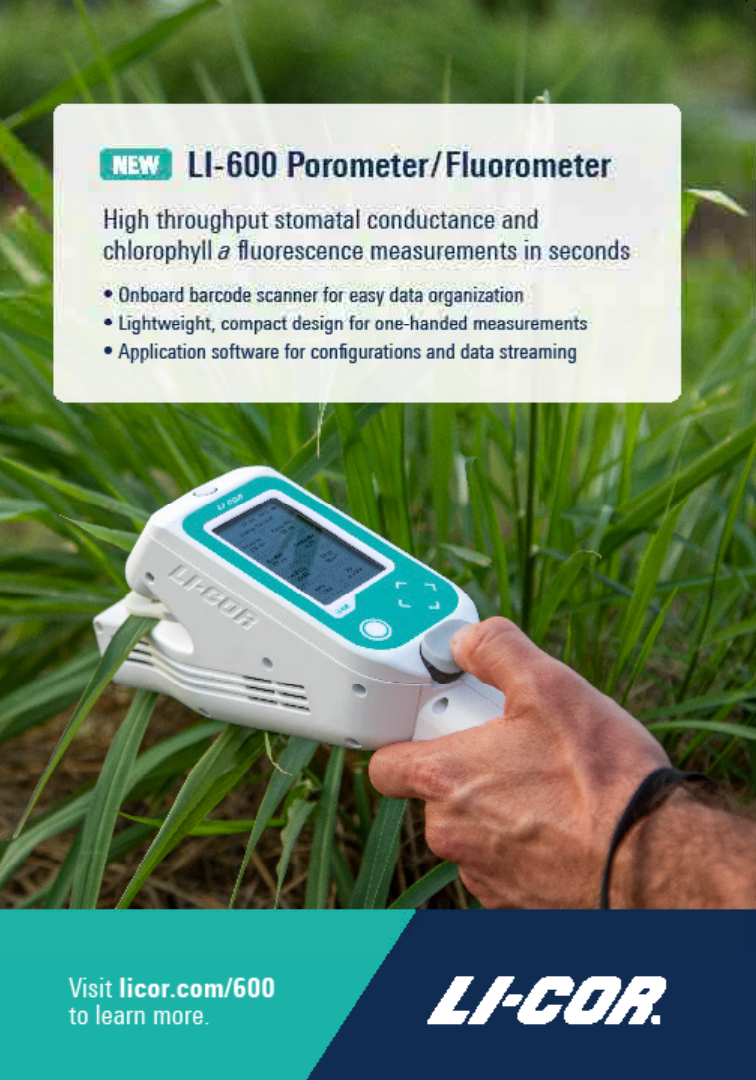

PHYSIOLOGICAL SECTION LI-COR PRIZES

Best Student Oral Presentation

Haley Branch, University of British Columbia, For the Presentation: Historical differences in

climate between populations alter responses to severe stress. (Co-Authors: Dylan R. Moxley

and Amy L. Angert)

Best Student Poster

Myriam “Mimi” Serrano, San Francisco State University, For the Presentation: Tracking

Leaf Trait Differentiation of Newly Diverging Subspecies of Chenopodium oahuense on the

Hawaiian Islands. (Co-Authors: Jason Cantley and Kevin A. Simonin)

PHYSIOLOGICAL SECTION

STUDENT PRESENTATION AND POSTER AWARDS

Best Student Oral Presentation

Jianfei Shao, University of Guelph, For the Presentation: Root trait plasticity in response to

contrasting phosphorus environments and its consequences for plant performance. (Co-

Author: Hafiz Maherali)

Best Student Poster

Gillian Gomer, University of Central Florida, For the Presentation: Consequences of Stress-

Induced Trait Plasticity in Cultivated Helianthus. (Co-Authors: Chase Mason and Eric

Goolsby)

MAYNARD MOSELEY AWARD

(DEVELOPMENTAL & STRUCTURAL AND PALEOBOTANICAL SECTIONS)

The Maynard F. Moseley Award was established in 1995 to honor a career of dedicated teaching, scholarship,

and service to the furtherance of the botanical sciences. Dr. Moseley, known to his students as “Dr. Mo”, died

Jan. 16, 2003 in Santa Barbara, CA, where he had been a professor since 1949. He was widely recognized

for his enthusiasm for and dedication to teaching and his students, as well as for his research using floral

and wood anatomy to understand the systematics and evolution of angiosperm taxa, especially waterlilies.

(PSB, Spring, 2003). The award is given to the best student paper, presented in either the Paleobotanical

or Developmental and Structural sessions, that advances our understanding of plant structure in an

evolutionary context.

Harold Suarez Baron, University of Antioquia, For the Presentation: Developmental and

genetic mechanisms underlying trichome formation in the Aristolochia (Aristolochiaceae:

Piperales) perianth. (Co-Authors: Favio González, Soraya Pelaz, Juan Fernando Alzate, Barbara

Ambrose, and Natalia Pabon Mora)

PSB 67(3) 2021

172

ECOLOGICAL SECTION STUDENT TRAVEL AWARDS

Mimi Serrano, San Francisco State University, Advisor: Dr. Kevin Simonin, For the

Presentation: Tracking Leaf Trait Differentiation of Newly Diverging Subspecies of Chenopodium

oahuense on the Hawaiian Islands

Laura Super, University of British Columbia, Advisor: Dr. Robert Guy, For the Presentation: The

impact of simulated climate change and nitrogen deposition on conifer phytobiomes and associated

vegetation (Co-author: Dr. Robert Guy)

Yingtong Wu, University of Missouri - St. Louis, Advisor: Dr. Robert E. Ricklefs, For the

Presentation: What Limits Species Ranges? Investigating the Effects of Biotic and Abiotic Factors on

Oaks (Quercus spp.) through Experiments and Field Survey (Co-author: Dr. Robert E. Ricklefs)

ECONOMIC BOTANY SECTION

STUDENT TRAVEL AWARDS

Best Student Ethnobotany Poster

Kaylan Reddy, Stellenbosch University, For the Poster: Sceletium Secrets - Exploring the

phytochemical and metabolomic diversity in the Sceletium genus. (Co-Authors: Gary Ivan

Stafford and Nokwanda Makunga)

Best Student Crops and Wild Relatives Poster

Juan Diego Rojas-Gutierrez, Purdue University, For the Poster: Genome-wide association

analysis of freezing tolerance in soft red winter wheat. (Co-Authors: Gwonjin Lee and

Christopher Oakley)

PHYTOCHEMICAL SECTION

PRESENTATION AWARDS

Liz Mahood, Cornell University, For the Presentation: Leveraging Integrative Omics Analyses

for Stress-Responsive Metabolic Pathway Elucidation in Brachypodium. (Co-Authors: Lars

Kruse, Alexandra Bennett, Armando Bravo, Maryam Ishka, Chinmaey Kelkar, Yulin Jiang,

Maria Harrison, Olean Vatamaniuk, and Gaurav Moghe)

Honorable Mention

Thiti Suttiyut, Purdue University, For the Presentation: Investigating the biochemical

evolution of the shikonin pathway in red gromwell (Lithospermum erythrorhizon). (Co-

Authors: Robert Auber, Manoj Ghaste, Jennifer Wisecaver, and Joshua Widhalm)

PSB 67(3) 2021

173

110 Haverhill Road, Suite 301

|

Amesbury, MA 01913 U.S.A.

|

+1 978.834.0505

|

sales@ppsystems.com

|

ppsystems.com

Elevate your research with the fastest,

most accurate portable leaf gas exchange

system available.

Measurements in seconds

Lightweight & compact

Simultaneous photosynthesis

& chlorophyll fluorescence

measurement

Ultrafast A/C

i

curves

Small system volume

advantage

•

Photosynthesis

•

Chlorophyll Fluorescence

•

Soil Respiration

•

Canopy Assimilation

•

Insect Respiration

@pp_systems

company/pp-systems

ppsystems.intl

ppsystemsinc

ppsystemsinc

CIRAS-3 Portable Photosynthesis System

Redefining the high-level research experience worldwide.

174

SPECIAL FEATURES

By David J. Asai

Senior Director, Science

Education

Howard Hughes Medical

Institute

[Editor’s Note: David Asai spoke at Botany 2021 for the

Belonging in Botany Lecture, Perspectives on DEI.]

The children’s story The Little Red Hen

(Dodge, 1874) is a metaphor for inertia. In

her efforts to be a change agent, the Little

Red Hen collided with the barriers protecting

the barnyard’s center of power. In this essay,

I present some thoughts on race, culture

change, and responsibility, and conclude with

my version of the tale of the Little Red Hen.

“RACE MATTERS”

(WEST, 1993)

Race matters to all of us, regardless of our

skin color or whether we are a victim of overt

discrimination. Race and racism are deeply

rooted in our national identity. Racism is not

a problem only for persons of color; it is an

American problem.

The Little Red Hen

and Culture Change

From our nation’s beginning, the racialization

of people has been used by the white center

of power to define who belongs and who does

not—who may immigrate, become a citizen,

vote, own property, and whom a person may

marry (Lepore, 2018). The term “white center

of power” is not about the skin color of those

who are in power or those who are on the

outside looking in. Instead, the “white center

of power” refers to a social structure created

by and for persons—almost all male—who

descended from white northern European

immigrants. Their perspectives became the

norms of our society, our economy, our

educational system, and our science.

SCIENCE IS COMPLICIT

The racialization of people and how it

has become weaponized is inextricably

rooted in science. The leading scientists of

their time wrongly claimed that there are

genetically distinct human races that evolved

independently (see, e.g., Gould, 1981). This

idea, in turn, allowed for the racialized

ranking of humans in terms of intelligence,

industriousness, ingenuity, sexuality, and

criminal behavior. The imprimatur of science

was the authoritative cover for colonization,

enslavement, and sterilization. The cells of

Henrietta Lacks, the men of Tuskegee, the

PSB 67(3) 2021

175

DNA of the Havasupai, the telescopes atop

Mauna Kea…. these are all reminders that

science is complicit in perpetuating and

reinforcing racism. Science helped create the

present culture of racialization and exclusion,

and so science has the responsibility of

replacing the old culture with a new one that

is centered on equity and inclusion.

TALK IS CHEAP

A characteristic of a white-centered system

is that it is unprepared and unwilling to

deeply examine race and racism. In the last

few years, and especially after the video-

recorded murder of George Floyd in May of

2020, America has, once again, dipped its toe

into the ocean of systemic racism. We have

marched in the streets, planted yard signs,

and toppled statues. Academic buildings

have been renamed, and carefully worded

statements claiming allyship with Black Lives

Matter have been published. But these are

the easy things, the superficial things. Much

harder is to change our culture—to walk our

talk.

Even as we boldly declare that now is the

time for a racial reckoning, too many liberals

and defenders of free speech are afraid to

even whisper the words “critical race theory,”

which recognizes that racism is systemic

and embedded in our policies and rules, our

practices and behaviors (see, e.g., George,

2021). The normalization of the white center

of power results in policies and rules that

naturally exclude Black and Brown people. As

Ezra Klein paraphrased Ibram Kendi (Klein,

2021), “Racists don’t make racist policies.

Racist policies make racists.”

When we use “scientific rigor” as the rationale

for our lack of diversity… when, in our

teaching and textbooks, we tell only the stories

of the white “founding fathers” of science…

when, in our recruiting of students and hiring

of faculty, we rely on a person’s pedigree as

a proxy for worthiness… when we focus on

individual prizes instead of encouraging

interdisciplinary collaboration… when we

do these and other things, we perpetuate the

white center of power.

PEERS

In science, we often refer to a person of color as

a “URM.” But that’s not right (e.g., Bensimon,

2016; Williams, 2021). The “M” word has two

definitions, neither of them appropriate. One,

“minority” is numerical. But persons of color

are not the numerical minority; in fact, 85%

of the world’s population are persons of non-

European ethnicities. The second definition of

“minority” is a pejorative—defining persons

as lesser, diminished, and subordinate.

The “UR” part of “URM” stands for

underrepresented, but underrepresentation is

the symptom and not the cause. The cause is

that the culture of science has systematically

excluded persons of color. Instead of “URM,”

I use “PEER,” which stands for Persons

Excluded from science because of their

Ethnicity or Race (Asai, 2020). PEERs in

science include Blacks/African Americans,

Latinx/Hispanic, and persons belonging to

populations indigenous to the United States

and its territories.

The system fails to keep PEERs in STEM

even though PEERs are well represented at

the start of the academic pathway. Today,

PSB 67 (3) 2021

176

PEERs are 32% of the U.S. population, 37%

of undergraduates, 21% of STEM bachelor’s

degrees, 12% of STEM PhDs, and 6% of

tenured faculty in STEM (NCSES, 2021).

The disproportionate shedding of PEERs

from STEM is not due to their lack of interest.

In fact, PEERs are over-represented among

students entering college intending to study

STEM. Nor is the disproportionate loss of

PEERs due simply to their lack of preparation.

In studies that control for important factors—

including high school math, family interest in

higher education, and family income—PEERs

leave STEM at much greater rates than non-

PEERs (Riegle-Crumb, 2019).

Among students entering college, the interest

in studying STEM is the same for PEERs and

non-PEERs. But the persistence in STEM by

each group is vastly different. PEERs intending

to major in STEM earn the bachelor’s degree

at only half the rate of non-PEERs, and earn

the PhD at only one-fourth the rate of non-

PEERs. More alarming is the fact that these

disparities in persistence have not changed in

at least three decades (Asai, 2020).

“FIX THE PEER” IS NOT

SUFFICIENT

In those three decades, gazillions of dollars

have been spent on a myriad of programs

aimed at increasing racial and ethnic diversity

in science. These interventions include, for

example, summer bridge programs, programs

to help students transition from community

college to the baccalaureate, remedial courses

and special advising, summer research

experiences, “minority” supplements to

federal research grants, and funds for “cluster

hiring.” Although these programs can benefit

the participants, they are not sufficient to

create systemic and sustained change.

These interventions are examples of a “fix the

PEER” (or “blame the victim”) mindset. The

“fix the PEER” mindset has these hallmarks:

• PEERs are treated as a commodity. The

system rewards us for collecting PEERs—

having more PEERs helps us win train-

ing grants and looks good when we are

undergoing departmental or university

review and accreditation. Too often,

PEERs are invisible except when it’s time

to illustrate brochures and websites.

• Interventions are aimed at helping the

PEER fit in… to assimilate into a scien-

tific culture that is not of their making.

As a result, PEERs and people from other

underrepresented groups are unable to be

their authentic selves when studying and

working in our institutions.

• And PEERs are often expected to bear

the burden of change. There are some

who claim that when Black and Brown

students dress nicely, show up to class on

time, sit in the front row, and ask ques-

tions, then institutional racism disap-

pears. And then there’s the “diversity tax,”

in which a student or faculty member

from an underrepresented group is asked

to serve on every committee—admis-

sions, recruiting, advising, “DEI”—be-

cause we depend on them to do our work

of advancing diversity.

PSB 67(3) 2021

177

CHANGING OUR CUTURE

Instead of fixing the PEERs, we must change

the culture of science and science education.

Culture is not ephemeral—it is structural and

it is manifested by behaviors (West, 1993).

In higher education and science, structures

and behaviors include how we select persons

who may enter science, the curriculum, the

policies and procedures that signal whether a

person belongs in science, and the system that

rewards certain behaviors.

Changing the culture means recognizing

PEERs as peers, rather than as a commodity.

Changing the culture means ensuring that

our structures—our policies, procedures,

curriculum, system of rewards—genuinely

reflect the values and perspectives of all the

participants, rather than expecting PEERs to

assimilate. And changing the culture means

that we who are currently in charge of the

system have the responsibility to change the

system, rather than placing the burden on

PEERs.

As we strive to change the culture, here are

three questions that can guide our work:

1. Who gets in and why? If we are

still relying on standardized tests like

the SAT and GRE, let us ask our-

selves why. These tests do not ac-

curately predict success in college

or graduate school (e.g., Hall et al.,

2017), but they correlate well with

family income and zip code (https://

reports.collegeboard.org/pdf/total-

group-2016.pdf). Success in the pro-

gram is a function of what happens

during the program rather than what

the student scored on a standardized

test before they entered the program.

In recruiting and promotions, let us

not rely too heavily on academic pedi-

gree and “the old boys network.” Before

we begin searching for more persons

of color, we—the search committee

and the hiring department—must first

be able to clearly articulate why diver-

sity is important to our department,

rather than depend on the candidates

to explain to us the value of diversity

(see Sensoy and DiAngelo, 2017).

2. How do we decide who is wor-

thy of staying? Let us first provide

all faculty opportunities and incen-

tives to learn inclusive pedagogical

and mentoring skills. Then let us cre-

ate reliable and fair methods to assess

the effectiveness and inclusivity of our

teaching and mentoring. And finally,

let us include those assessments in our

rewards system, including promotion

and tenure.

3. What do we celebrate? In our

teaching, let us tell the stories of cur-

rent, living scientists from all back-

grounds, instead of only teaching the

discoveries of the “white founding

fathers.” And in our newsletters, web-

sites, and awards, let us recognize ac-

complishments of all types, not only

for individual achievements but also

for effective collaborations and effec-

tive cross-disciplinary work.

TIME

You don’t need my sermon to know what to

do. As a community, we have plenty of good

ideas, and we have many persons willing

to be change agents who are committed to

implement those ideas. Yet, we remain stuck.

PSB 67 (3) 2021

178

Let’s consider what typically happens. We

go to a meeting or read an essay. We get

fired up. We see all of the ways that we can

get better. We create lists of things to do, and

we debate their relative priorities. We might

even write a “white paper” or publish a list

of recommendations. And then we return to

the realities of our jobs, and we are almost

instantly consumed and subsumed by the

daily hard work of everything else we do. We

might want change, but we just don’t have

the time to do it. The real barrier to genuine

culture change is the lack of time.

We need time to reflect on how the structures

of science and science education uphold the

white center of power, and how we erect

barriers to preserve the center. We need time

to learn the skills of inclusion and practice the

skills of listening, so that we can talk candidly

about race, racism, and cultural privilege. And

we need time to hold ourselves accountable by

taking action, and then assess the effectiveness

of our actions.

To make time for reflection, learning, and

accountability means we also have to not do

some things. And this brings me to my “what

if” dreaming.

What if our department or school were to

suspend all other activities for a few weeks in

the autumn so that faculty, staff, and students

could engage in facilitated reflection and

learning, then collectively decide on one or two

things we want to accomplish in the coming

months. We should set realistic goals that will

lead to bigger outcomes. For example, we might

choose to begin the process by examining the

introductory science curriculum, or dig into

the criteria for faculty promotion and tenure.

In the spring, we would again suspend all

other activities and come together to reflect

on the past year, to assess our progress, and

to hold ourselves accountable. And we would

make this a recurring habit, regularly stepping

away from everything else to focus on equity

and inclusion.

Of course, there are millions of reasons why we

can’t try my idea. But if equity and inclusion

are really institutional values, if we truly want

to become allies to PEERs, if we really aspire

to be anti-racist, then we must find a way to

learn how to walk our talk, to truly change

our culture. Culture change does not happen

because of fancy rhetoric or strategic plans;

it will happen only when we find the time to

change our structures and behaviors. The goal

of diversity through equity is far too important

for us to give up just because it is hard, or

because it is new, or because it makes us

uncomfortable, or because we don’t have time.

Let us all commit to culture change through

reflection, learning, and accountability. Now

is the time to begin.

THE LITTLE RED HEN

REVISITED

One spring day, the Little Red Hen had an

idea. She thought that it would be a great

improvement to the barnyard if they could add